In and out of the Lemonheads, Evan Dando has occupied conflicting personae over the past 30 years: himbo bubblehead and underappreciated power-pop savant, a privileged prep playacting as Gram Parsons, wannabe Gallagher brother, and tragicomic, troubled survivor. While Dando’s public appearances of late have tended toward the former descriptions, the ongoing reissue of the Lemonheads’ major label output has attempted to shift the focus toward the latter, a just reward for a band that now serves as a model for much of what’s left of classic indie rock. The campaign now reaches 1993’s Come On Feel the Lemonheads, the last album that stood between alt-rock fame and tabloid infamy, the one where Dando was everything everyone ever said he was, all at once.

Though the album title reflects early ’90s irony, there’s an underlying truth in its intentions: Come On Feel the Lemonheads was a charm offensive by a band that was still largely known for a kitschy cover song, a nod to their ascending star and desire to capitalize on it. The videos for “Into Your Arms” and “It’s About Time” are careful to reiterate that we are meant to see the Lemonheads as a band, one that’s still having a wonderful time together. Bassist Nic Dalton and drummer David Ryan get plenty of camera time, and each of them probably would’ve been the “cute” one in 99 percent of the bands with whom they shared Buzz Bin space. But if the viewer is supposed to get familiar with the Lemonheads, they’re getting intimate with Dando, who’s framed in a variety of settings where one can imagine falling in love—in a forest, cuddled up on a couch, at an impromptu street concert, in a bathtub.

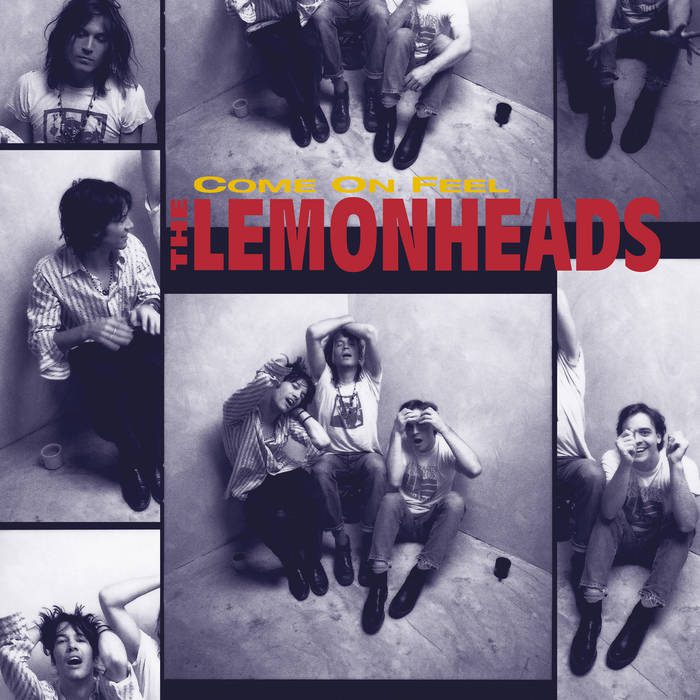

And of course, only Dando’s face is shown in full on the album cover, gazing wistfully into some uncertain future where someone of his talents will probably end up just fine. But after a brief spell of time when the Lemonheads were a fixture on MTV, I mostly remember seeing that face staring back at me from cluttered racks at Disc Go Round, Wherehouse, Plan 9, and wherever else I shopped for used CDs in the ’90s. The album’s cut-out bin status isn’t necessarily indicative of its quality—there were also quite a few copies of Transmissions From the Satellite Heart, Last Splash, Star, and File Under: Easy Listening, records by indie darlings who’d scored an unexpected hit that didn’t quite prepare mall-walkers for their weirdness.

But there were plenty of examples of sophomore slumps, time capsules from alt-rock’s flop era, and general letdowns coasting off the goodwill from a previous hit. The Lemonheads somehow managed to fit both categories. Less than a year after Dando pinched his nose and covered a song he “hated” for the 25th anniversary of The Graduate, Come On Feel the Lemonheads had enough juice to peak at No. 56 on Billboard. Though nowhere near as crass as the autopilot pop-punk of “Mrs. Robinson,” or even 1989’s take on Suzanne Vega’s “Luka,” the band’s biggest hit was a cover all the same, albeit one from someone in the Lemonheads. Dalton replaced Juliana Hatfield on bass following It’s a Shame About Ray and contributed a curio from his previous band, the Love Positions. In its original form, “Into Your Arms” was 100 seconds of state-of-the-art K Records worship: no drums, gooey, pitch-shifted lyrics, on an album called Billiepeebup with a bunch of pink hearts on the cover. The red-blooded, full-bodied version that ended up on radio proved that Dando was no Kurt Cobain in terms of comportment, but still a valuable interpreter for Alternative Nation and its financiers: someone who could smuggle Boston college rock and Australian twee into places they couldn’t get to on their own.

The ensuing singles continue to shine outside of their original context as songs that couldn’t sustain the momentum of “Into Your Arms.” “The Great Big No” pivots from their standard, strummy college rock jangle to an uneasy, dissonant chorus, almost like a purified version of shoegaze, heavier than anything the Lemonheads had done even when they were a Dinosaur Jr. worship band. “It’s About Time” and “Down About It” reiterate the strengths of It’s a Shame About Ray, Dando’s shopworn voice and gnomic hooks suggesting vast experience if not deep thoughts—that there are stories here, if you’re willing to wait for them. Fittingly, the last great song the Lemonheads would write would be called “If I Could Talk I’d Tell You.”

These highlights all occur within the first 10 or so minutes of Come On Feel the Lemonheads, creating the illusory effect of an album that always seems to be better than you remember it, or at least better than the critics thought then. “Evan Dando is a good-looking guy with more luck than talent and more talent than brains who conceals his narcissism beneath an unassuming suburban drawl,” Robert Christgau wrote in his 1993 “Turkey Shoot,” a cascade of assumptions that didn’t need to be scrutinized because the first claim was clearly true. But this gets to an irony that’s made reassessment of the Lemonheads so compelling: Dando was the rare male musician subject to the standards by which many female alt-rock artists were judged, wherein the art made their appearance, romantic relationships, and drug use fair game for gossip and assumption. And unlike Cobain, Eddie Vedder, Chris Cornell, or other male, alt-rock sex symbols of the era, Dando didn’t outwardly shy away from that gaze. When he acknowledges the obvious on “Paid to Smile,” he’s more bemused than anything (“I can work the handle on any car/It’s really not that hard”), empathizing with anyone in the same position. Someone’s gonna do it, why not him?

It’s just as likely that Dando wasn’t taken particularly seriously because he didn’t take himself all that seriously either; as Come On Feel the Lemonheads progresses, he marvels at the Coriolis Effect, reads the labels on his spice rack, and calls out the chords he’s playing on “Dawn Can’t Decide.” Among my few middle school peers aware of the Lemonheads’ existence, “Big Gay Heart” was the most transgressive thing imaginable at the time, not even so much for its hook, but its earnest embrace of country music—we were still three years away from Ween’s 12 Golden Country Greats. But at that point “Big Gay Heart” was only the second Lemonheads song longer than four minutes (1990’s “[The] Door” was about 75 percent guitar solo) and still lasted twice as long as it should have. The same fate awaited “Style,” which shrugs at Dando’s spiraling substance abuse (“Don’t wanna get stoned/But I don’t wanna not get stoned”) that was later reprised as “Rick James Style,” a murky, zombie-funk jam that, in an icky bit of stunt casting, actually featured Rick James.

The remainder is mostly unremarkable: Hüsker Dü worship tamped down by the Robb Brothers’ dated production, an alt-country throwaway featuring a Flying Burrito Brother, swapping Hatfield for Belinda Carlisle on backing vocals during the cloying “I’ll Do It Anyway.” Shaggy where It’s a Shame About Ray was succinct and sharp, Come On Feel the Lemonheads feels about twice as long as its predecessor, and that’s before “Jello Fund.” It would’ve been more fashionable to make the 15-minute studio jam a hidden track, but “Jello Fund” feels like apt metacriticism of a band with too many ideas and not enough follow-through.

Revisiting Come On Feel the Lemonheads can be revelatory in spite of its unevenness—with some scruffier production, the jumbled mix of ZooMass revivalism, power-pop sparkle, and complementary co-ed vocals could’ve been passed around the Run for Cover office at any point in the past 10 years; latter day Tigers Jaw was more or less invented when Hatfield came in to steal the last chorus of “Down About It.” I wish I’d had someone in my teenage ear to put this band in proper context, as a gateway to the Pixies or Throwing Muses or 4AD rather than a cuter Cracker or Soul Asylum. As with the reissues of Lovey and It’s a Shame About Ray, the deluxe version offers demos and outtakes that justify a physical reissue in 2023 and not much else; perhaps the more authentic experience would be copping a $2 used copy. But the cover has changed, and the image feels far more accurate now: Dando’s no longer the center, but slumped off in the top left corner, at the top of his game and well aware he’s about to hit bottom.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.