The Durutti Column’s 1980 debut album—confusingly titled The Return of the Durutti Column—originally came packaged in a sandpaper sleeve, a detail that couldn’t have been more at odds with the music inside. The sandpaper was a Situationist prank dreamed up in part by Factory Records boss Tony Wilson, who signed the group to his label, but there was nothing abrasive about the sound of the record, which set Vini Reilly’s quicksilver guitar melodies against Martin Hannett’s ghostly atmospheres and spare electronic production.

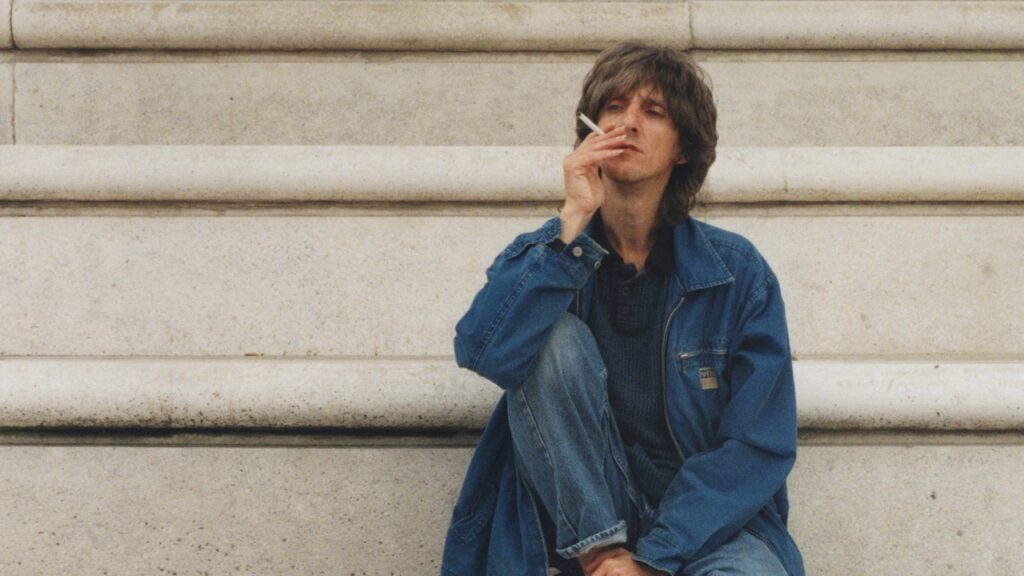

Although it had begun as a full-band effort—contributing two songs on 1978’s A Factory Sample EP, alongside Joy Division and Cabaret Voltaire—the Durutti Column was in effect the solo project of Reilly. Twenty-six years old when he released his debut, he had been playing guitar for 15 years and studying nearly as long, and after a brief stint crunching power chords in a Manchester band called Ed Banger and the Nosebleeds, he bought a £12 acoustic guitar and unlearned everything that punk had taught him, fashioning an idiosyncratic style out of bits and pieces of jazz, classical, blues, and flamenco.

Led by his own quixotic impulses, Reilly developed a singular style across dozens of albums released over the following decades. The essence of his sound is his tone: at once liquid and crystalline, and touched by quick, nervous vibrato, like a dewdrop quivering on a blade of grass. Combining expressive phrases with unusual voicings and unpredictable chord changes, his playing often has an almost discursive quality, as though he had transcribed the cadences of speech for his six-stringed instrument.

Reilly, who suffered a series of strokes in 2010 that left him unable to play, was never a particularly famous figure, but his 1980s albums frequently landed in the Top 10 of the UK independent charts, and over the years he amassed significant fans: John Frusciante reportedly called him “the greatest guitarist in the world.” It’s hard to overstate Reilly’s influence in the 1980s and ’90s, even as he swam against the current. He opted for a clean signal when distortion was de rigueur, and jazzy harmonies when barre chords were standard; he displayed virtuoso talent in an era when many of his post-punk peers were picking up their instruments for the first time. Year after year, the Durutti Column’s music—patient, reserved, catlike—appears more prescient. Today we would call it dream pop, but back then, there was no name for his sui generis brand of largely instrumental, quasi-ambient avant-pop. “Call it new music, but not radical or unpleasant,” Reilly said, with characteristic wryness.

Even as Reilly’s tone retained its unique character, his music evolved in significant ways over the years. Moving on from his minimalist origins, he folded in harp, strings, and cor anglais before experimenting with drum machines and samplers. Some of the vocal loops on 1989’s Vini Reilly anticipate Moby’s Play, while 1990’s Obey the Time was in conversation with acid house. By 1996’s Fidelity, he was citing the influence of UK rave duo Orbital. With 1998’s Time Was Gigantic… When We Were Kids—newly remastered and reissued with five additional songs—Reilly made a subtle but unmistakable shift toward pop music, due in large part to the vocal contributions of a singer named Eley Rudge.

This wasn’t the first time Reilly worked with vocals. Though The Return of the Durutti Column was entirely instrumental, he began singing with 1981’s LC, and his warmly mopey murmur became a frequent feature of his albums. (In his memoir 24 Hour Party People, Wilson jokes that he tried to persuade Reilly to stop singing, but “failed miserably.”) Guest vocalists became commonplace on Durutti albums beginning with 1987’s The Guitar and Other Machines, and Rudge turned up on two songs on 1996’s Fidelity. But Time Was Gigantic feels like a showcase for her singing, prominently featuring her on six of 11 songs.

On the opening “Organ Donor,” Rudge seems a perfect foil for Reilly’s playing, which piles up in sparkling layers. She has a dulcet tone, and she pursues a sing-songy melodic line that complements his own harmonic voicings without overpowering them. In its blissful tone and mood, the song feels like a response to the gossamer pop of the Cocteau Twins’ Heaven or Las Vegas, released eight years prior. But Rudge’s other appearances on the album are a mixed bag. Her tone is frequently so sweet that it comes off as cloying; her melodic choices suggest a less bluesy Edie Brickell or a less breathy Harriet Wheeler, of the Sundays. Where Reilly’s playing is mercurial, she’s one-note; while he slides effortlessly over the fretboard, her vocal tics sound affected. She’s not a bad singer, but she’s conventional in a way that doesn’t suit the subtleties of Reilly’s playing. It doesn’t help that the lyrics gravitate toward rote rhymes and facile sentiments (“Let’s make love again/Just one more time/I’ll be yours/You’ll be mine”). Her singing has the distinct air of a ’90s coffeehouse.

Fortunately, Time Was Gigantic remains a more nuanced and exploratory album than Rudge’s lead vocals might suggest. The instrumental “Pigeon” is cool and dusky, Reilly’s multi-tracked guitar trailing long strings of echo behind. In “Twenty Trees,” Reilly takes the mic, and his voice—although buried in the mix, as usual—is warm and reassuring, intimate in its fragility. It’s an unusual song for the Durutti Column, swollen with string synths and a looping tabla rhythm; the guitar is relegated to a silvery filigree. Tabla also figures prominently on “I B Yours,” its rippling patterns mirrored in Reilly’s quick-fingered runs. And on “For Rachel,” he mixes together a trip-hop beat with contrapuntal guitar lines, one flamenco-inspired and the other vaguely West African, along with choral loops and what might be a vocoder. It may lack the grace of his early work, but it’s gratifying to hear him experimenting like this, seeking out new applications for his familiar guitar tone.

Five previously unreleased bonus tracks mostly break with the album’s mood. “Kiss of Def” is a thundering drum’n’bass remix of album cut “My Last Kiss”; “New Order Tribute” is a synthy, squelchy homage to his erstwhile labelmates that he banged out “for fun” in 90 minutes, according to the liner notes. Perhaps the most intriguing bonus cut is the 94-second “It’s Your Life, Babe”—an almost entirely atmospheric track with an unmistakably Lynchian cast featuring ghostly, operatic singing from Ruth-Ann Boyle, who also appeared on 1994’s Sex & Death. Hearing this sketch, it’s tempting to wonder what Reilly might have done had his fascination with Orbital led him in a more explicitly ambient direction. It’s those hints of possible futures that make Time Was Gigantic worthwhile, if not the ideal starting point. Reilly’s fractal spirals of notes always suggested overgrown gardens of forking paths; his catalog is so rich, his ideas so engrossing, that even the detours and dead ends make for rewarding wandering.