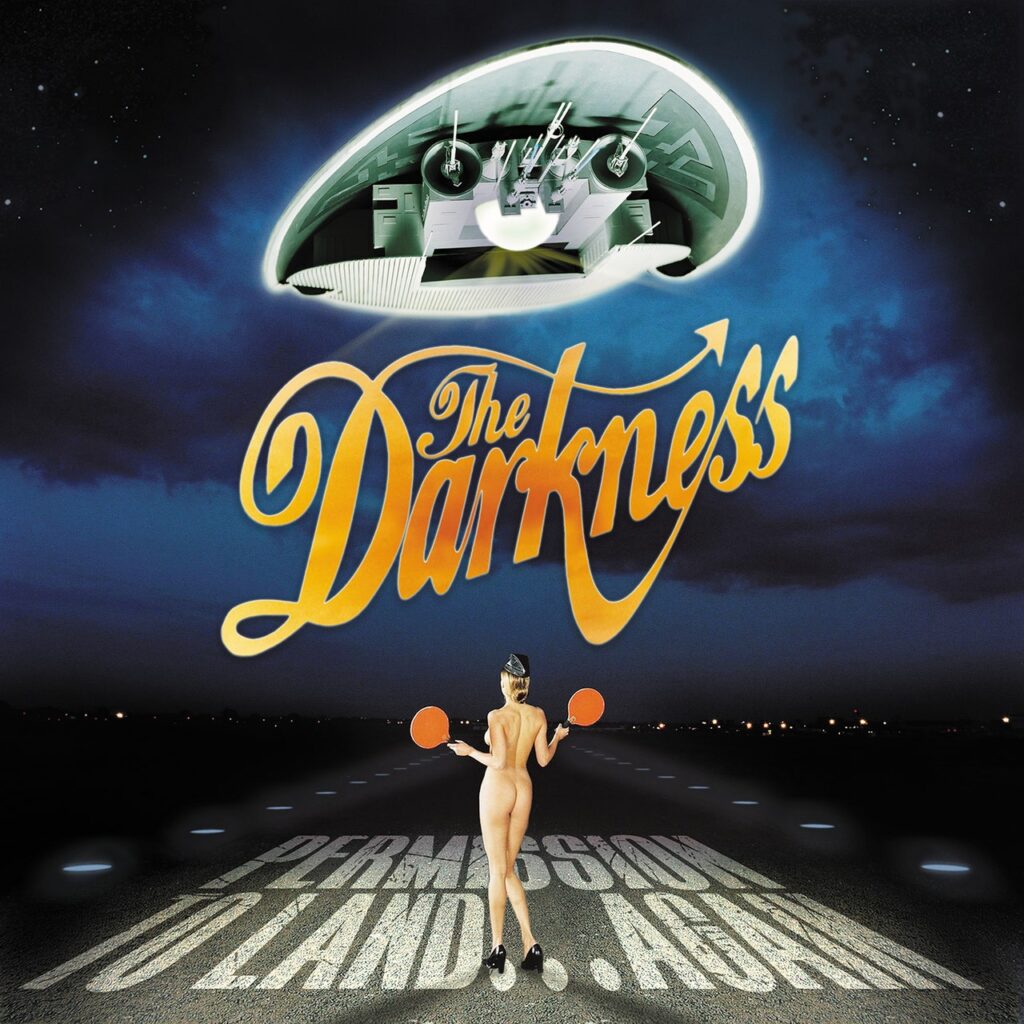

The Darkness pursued rock stardom in the same way that people nowadays strive to be pro running backs or music journalists: headlong, and without care for how the position is currently valued. As East Anglian teenagers in the early ’90s—with alt-rock and baggy Madchester in commercial ascendance—brothers Dan and Justin Hawkins were obsessed with the heavy acts of their childhoods. They pored over Brian May’s guitar tone, Aerosmith’s album sequencing (always close with a power ballad), and the proper design of catsuits. Dan cut his teeth playing outmoded styles like thrash metal and prog, moving from drums to bass when he joined Justin’s covers band. It was a part-time gig for Justin; in 1997 he had started a business composing soundalikes for commercials: tunes that would suggest their sources without being legally actionable. It was this work that bankrolled the recording of the Darkness’ 2003 debut, Permission to Land: a defiantly unfashionable set of glammy, cheeky hard rock that briefly made the band the toast of UK pop.

At the turn of the 21st century, there was no shortage of acts mining musical comedy from the same rocks as the Darkness. In England, the band was preceded by the self-mythologizing Wildhearts, who mixed an omnivorous ‘60s pop sensibility with buzzsaw rock‘n’roll. Scandinavia boasted punked-up glam from the likes of the Hives, Backyard Babies, and Turbonegro. America had Satanicide (a scraggly-wigged, live hair-metal act for NY hipsters), Tenacious D (the absurdist pomp-rock duo of Kyle Gass and Jack Black), and Steel Panther (an international festival draw that rendered the cock-rock deathstyle with grim fidelity). But the Darkness were distinguished by their ambition. In sound and bearing, they presented as chart royalty; they were committed to the bit on a cellular level. They took rock-as-form very seriously, which freed them to be frivolous everywhere else.

Roughly timed to the 20th anniversary of the album’s US release, Permission to Land… Again doesn’t complicate the legacy of the Darkness. Instead, it honors it by providing more: more twin-guitar flash, more careening falsetto, more high-concept rockers. From the beginning, The Darkness walked a tightrope between the dual skyscrapers of Queen and AC/DC. At one end, haughty yet humane grandeur; at the other, snarling, cranked-up minimalism. Difficult enough work, but the real highwire act were the faces the band pulled along the line. The Darkness never fully embraced the comedy-rock label; being wiseasses just came naturally. Like a Kerrang!-approved Sparks, they spliced surging glam rock and power ballads with lyrics about jerking off and the existential unfairness of contracting an STI. Even if the texts weren’t especially clever, their deployment often was.

And when the Darkness did play it straight, the result could be incandescent. The deathless single “I Believe in a Thing Called Love”—which debuted at No. 2 in the UK—pairs a crunchy AOR riff with a half-yodeled chorus straight out of “Focus.” There are two couplets masquerading as verses; everything’s a race to the giddy nonsense of the refrain. When the trash can ending hits, it’s as if the song is taking its own bow. The nostalgic late-Kinks power-pop of “Friday Night” was an academic exercise—“Lyrically, I realized people liked songs with lists in,” Justin Hawkins recalled in 2013—contrasting the titular dance night with a list of extracurriculars (“I got ping-pong on Wednesday/Needlework on Thursday”) that would exhaust Max Fischer. The final result is touching rather than rote, even when, right before the solo, Hawkins purrs like a tiger.

Then as now, one’s enjoyment of the Darkness hinges on their lead singer. If Freddie Mercury’s voice was a Ferrari 250 GTO (exquisitely rare, with remarkable handling and impeccable style) then Hawkins’ was a Dodge Viper: brutishly powerful but prone to spinning right off the track. Hawkins had always fancied himself a classic-rock vocalist in the Steven Tyler mode; it was only after recording wrapped for Permission to Land that he realized he was, in fact, channeling Kate Bush. At the angrier edge of the Darkness’s sound, the seams would show. In a vacuum, Hawkins repeatedly hollering “get your hands off of my woman, motherfucker” is funny. In practice, he sounds like an exotic bird screeching at rivals. Still, that instinct toward bad taste was just one more way in which the Darkness were heirs to hard-rock tradition.

That instinct crops up frequently within Permission to Land… Again’s collection of B-sides and non-album tracks. Sometimes the result is merely goofy. The backseat-sex celebration of “Makin Out” doubles as an AC/DC tribute, right down to the introductory legato. The anti-cyber screed “Physical Sex” was dated the minute they laid it down: “’Cause a fuck should be multisensory/And you just can’t smell an email.” Sometimes, as on “How Dare You Call This Love?”—a swaying Thin Lizzy-style ballad about anticipating the age of consent—it’s rancid. Other cuts find the band nudging into new territories: “Curse of the Tollund Man” is a proggish alternate history with a spaghetti-western intro and the brothers’ uncanniest imitation of Brian May’s Red Special. The synth-spangled “Planning Permission” draws on Justin’s brief career in construction to craft a sort of subcontractor’s love song: “Fittings to choose, color charts to peruse/I’ve got a trowel and I ain’t afraid to use it.”

The box also includes three live sets from 2003 and 2004, the first two of which—a slot at Knebworth Festival in support of Robbie Williams and a triumphant London homecoming at The Astoria—are included on DVD. More than anything, they reveal just how on the Darkness were. Their eagerness to entertain was only exceeded by their confidence. The banter is minimal; the showcase is the tunes. By the time of the 2004 Wembley set, the band had even more of them. They close with “Christmas Time (Don’t Let the Bells End),” their entry in the 2003 UK Christmas No. 1 sweepstakes. It was a shameless power ballad that crammed Slade, Queen and a children’s choir into the same stocking; it was kept from the top spot by Michael Andrews and Gary Jules’ cover of “Mad World.” The Darkness never told a funnier joke.

The Wembley concert also features several cuts from the Darkness’ in-process second LP, released in 2005. The circumstances of One Way Ticket to Hell… and Back were so fraught as to border on parodic. Bassist Frankie Poullain quit the band in the early stages of recording, only to be replaced by Richie Edwards, the Darkness’ guitar tech. The sessions were overseen by the legendary producer Roy Thomas Baker (Queen, The Cars, Journey), who indulged the band’s every whim: hundreds of guitar overdubs for Dan, a pan flute custom-made (and recorded!) in Peru for Justin. The album spawned two No. 8 hits but didn’t match Permission’s sales; within a year, Justin would leave the Darkness to enter rehab, resulting in Atlantic dropping the band, which split up soon afterward.

The original Darkness lineup reunited in 2011, immediately scoring a gig opening for Lady Gaga, who was going through a bit of a hard-rock phase herself. Though the endlessly quotable Poullain remains, the workmanlike (and decidedly non-glam) drummer Ed Graham left in 2014. In yet another testament to the Darkness’ successful insinuation into rock history, their current drummer is Rufus Tiger Taylor, son of Queen’s Roger Taylor. The Darkness had emulated their heroes in all ways except one: the slow build to success. Permission to Land arrived as a fully formulated antidote to nu-rock stodge, making the quartet the biggest act out of Lowestoft since Benjamin Britten. The band’s image was irresistible but neatly pegged, and though their ensuing career has been a catsuited compendium of all things heavy, pop culture only has so much room on the rack.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.