Before he became a queer disco icon, Sylvester had already cast himself in a movie “in which he was the fabulous star.” Between joining the Disquotays—a glamorous gang of teenage drag queens and trans women—and meeting Hi-NRG dance music producer Patrick Cowley, Sylvester found a spotlight with the San Francisco-based performance art stage troupe the Cockettes. They provided the opportunity to showcase his formative jazz, blues, and gospel influences, looking back to the 1930s and ’40s while dressing the part. In this intimate collection of his earliest known recordings, the 22-year-old Sylvester learns songs as the tape rolls, his signature falsetto sounding fully formed.

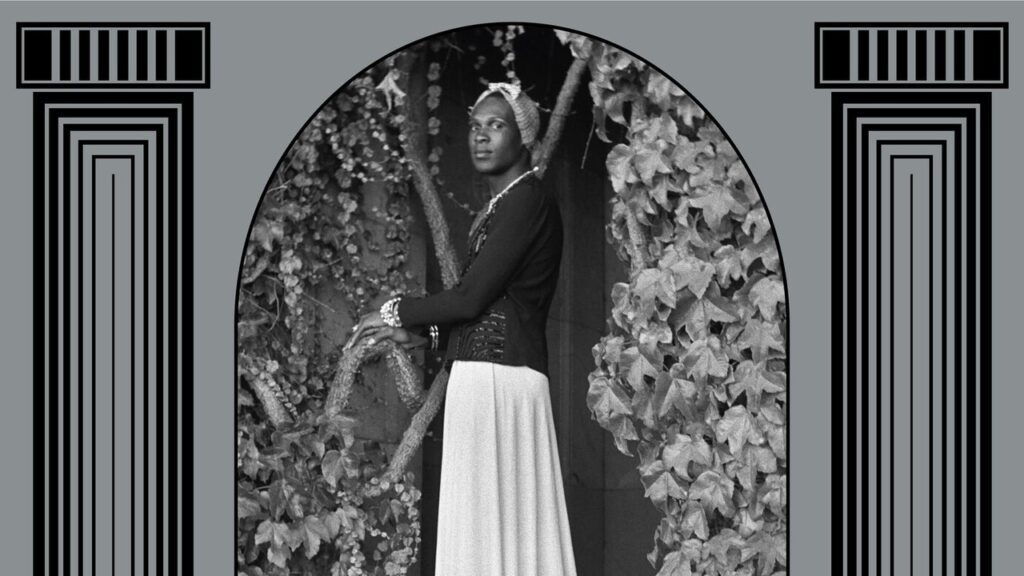

According to his biographer, sociology professor Joshua Gamson, Sylvester wasn’t a perfect fit for the LSD-laced hippies he joined in the early 1970s: “He usually stood a few feet back, among the Cockettes but never quite one of them.” While they dropped acid and painted their faces in psychedelic colors, Sylvester sipped champagne and wore pretty dresses like Josephine Baker. He met an ally in Cockettes piano player Peter Mintun, who shared Sylvester’s love of vintage fashion and popular songs from the Prohibition Era. With his pencil-thin mustache and the keys to his father’s 1936 Ford Coupe, Mintun drove Sylvester around San Francisco, snapping the time-warping photos that accompany this album.

One summer afternoon in 1970, Sylvester and Mintun sat down with a collection of sheet music, setting up a fancy microphone and a tape recorder next to an upright piano. Their recordings weren’t intended for public consumption, just used to learn songs they would perform in the Cockettes’ midnight shows. If there’s a throughline to be found in their chosen cuts, it’s the theme of love and loss as represented by changes to the environment. George and Ira Gershwin’s “A Foggy Day” turns London’s pea-soup air pollution into a metaphor for loneliness. The narrator of “Stormy Weather,” written by The Wizard of Oz composer Harold Arlen, laments the rain “since my man and I ain’t together.” Even the clear skies of “Happy Days Are Here Again” have a trace of melancholy as Syvester stretches notes out over twinkling keys. Yet in the snippets of conversation between him and Mintun, they sound like two friends at ease.

As the afternoon goes on, both the song selections and performances become more playful. On their incomplete reading of “Viper’s Drag,” a ragtime number adapted by Fats Waller from the original version by Cab Calloway, Sylvester’s wordless scats can’t keep pace with Mintun’s fingers flying across the keys. The session’s most lively song is the dance tune “Carioca” (“It’s not a foxtrot or a polka”), as the duo messes around, pausing to allow fellow Cockette John Rothermel to join on maracas. “Indian Love Call”—familiar thanks to the appearance of Slim Whitman’s yodeling rendition in Mars Attacks! and Asteroid City—becomes a full-throated duet before the singers collapse into giggles. The tape ends with a brief attempt at “When My Dreamboat Comes Home,” as Sylvester works out the melody in real time. We don’t hear the final version he and Mintun may have finished together, but it’s a happy conclusion to their lonely laments.

Like Stevie Nicks warming up with “Wild Heart” while getting her makeup done, this rehearsal tape feels like listening in on a casual hangout, free from the pressures of onstage performance. Sylvester’s Private Recordings, August 1970 is only essential for superfans, but there are gorgeous moments that illuminate how he would become a chart-topping star. His aching take on “God Bless the Child” surpasses the sadness of Billie Holiday as he salutes a young person with money who can “just worry ’bout nothin’/’Cause he’s got his own.” Sylvester dressed to the nines in gowns and furs while embodying the songs of an elegant diva because it’s the role he was born to play.