Techno, in 2023, is far removed from its roots. It is a keyword for lifestyle playlists. It sells tickets to clubs and festivals. It is merch. But techno, for the musician and writer Deforrest Brown Jr., is worth saving.

Assembling a Black Counter Culture, Brown’s 2022 “critical history” of techno, aims in part to reclaim the term for its originators in Black Detroit and those in their lineage. In the early 1980s, when Juan Atkins coined the name for the futuristic music he and his friends were making with synthesizers and drum machines in their bedrooms and basements, the present-day notion of a techno club did not yet exist, and neither did the formal and unspoken conventions that emerged after such places began popping up in Europe in response to the Detroit sound: the premise that an uninterrupted journey from one track to another, accompanied by strobing lights, synthetic fog, and strong drugs, was the ideal context for hearing this music; the standards of tempo and structure, developed to aid the DJ’s seamless mixing; the presumption that most of the people dancing their way through this shadowy wonderland would be white.

Brown, who also releases albums as Speaker Music, calls himself a “theorist, journalist, curator, visual artist, and by necessity, a musician.” His artist biography offers no clarification for the mysterious clause that qualifies the last item on that list. One way to interpret it is that Brown feels compelled to create music that is truer to the spirit of Detroit techno than the stuff you might hear on any given night at Berghain or the Basement: to make techno that lives up to its name. He has positioned Techxodus, his latest album, as a musical epilogue to Assembling a Black Counter Culture, and its opening seconds, in which a disembodied voice offers a working definition of techno—“Black music that sounds technological, rather than music made with technology”—make no secret of his weighty conceptual intent. The music defies any expectations a contemporary clubgoer might have of its genre tag, but it doesn’t much resemble old-school Detroit techno either. Brown is not a reactionary or a nostalgist: The music he loves, after all, arose from an attempt to break with tradition and find the sounds of the future. Rather than simply recreating the past, he imagines a new trajectory for techno, a sort of alternate history in which the music continued to grow and change according to its original precepts as a form of Black sonic expression, instead of the norms that club culture imposed on it.

Brown is particularly reverent of Drexciya, the Detroit group led by the late James Stinson, which contextualized its music within an elaborate mythology involving an aquatic civilization descended from Black children and pregnant women who were thrown overboard from transatlantic slave ships, whose members wage secret war on the white capitalist world order. (Abu Qadim Haqq, who created Drexciya’s visual art, designed the covers of both Techxodus and Assembling a Black Counter Culture.) One distinguishing characteristic of Drexciya’s music was the way Stinson and his collaborators contrasted the metronomic rhythms of sequencers with the unsteady expressiveness of human touch. A bassline might repeat with unchanging precision while an improvisatory keyboard melody dips and weaves atop like a rider on a wave.

Techxodus radically expands on this dynamic. Bit-crushed samples and laser-like synthesizer sounds cut aggressively against the prevailing rhythmic currents of “Holosonic Rebellion” and “Futurhythmic Bop.” On “Jes Grew,” a sample of a saxophone solo is mangled by what sounds like an unconventional use of time-stretching, a feature of many digital audio workstations that allows you to change a sound’s tempo without affecting its pitch, or vice versa. Brown ignores this benign use case to instead explore what time-stretching does when pushed past its limits, twisting the sound of the sax into loops that stutter and spasm. These digital artifacts have their own rhythmic logic, separate from both the grid that organizes the rest of the track—and, I imagine, from the saxophonist’s original phrasing. But within their glitchy unpredictability, there is also the pained and ecstatic humanity of the blues, screaming to break through.

The drum patterns across Techxodus, whether programmed or played freehand, destabilize the very idea of a beat. In its rhythmic maximalism, and its uncanny juxtaposition of drums that are clearly synthetic with those that sound like crisply recorded samples of a live kit, the album often recalls the avant-garde footwork of Jlin, Brown’s Planet Mu labelmate. He has spoken movingly about the impact her music has had on him, and it’s easy to understand why. A former steel worker from the hollowed-out industrial hub of Gary, Indiana, making music whose mechanistic contours gesture ambiguously at a world beyond the toil of the present, she strikes a clear parallel to Brown’s heroes working in Detroit during the decline of the American automotive industry. But where Jlin’s music, even at its densest, seems highly ordered, carrying a certain balletic poise, Brown’s seems wild, impulsive, raw. I don’t know how he makes it, but I imagine him sweating it out over a bank of sample pads, hammering away at them like a technologically augmented free-jazz drummer.

In a 2020 interview with Tone Glow, Brown addressed white listeners, musicians, and critics who misapprehend Black music, techno included. “What they’re seeing with this Eurocentric view of sound and music composition is systems,” he said in part. “They’re seeing nodes in a system moving along a linear path for satisfying or not satisfying rises and falls and conclusions—when what’s actually happening is a sort of speaking in tongues.” Where contemporary techno listeners are conditioned to expect that a particular element—a hi-hat, a bass drum, a synth—once introduced, will continue to perform small variations of the same basic function, Brown lets his sounds run free. A drone turns clipped and percussive, contributing to the rhythmic onslaught it once painted over. Midway through “Feenin,” a white-hot surge of electronic distortion arrives abruptly to envelop the entire mix, so loud and abrasive that I can’t help but wonder whether Brown had to lobby against a mastering engineer to keep it in. It sounds thrillingly, terrifyingly wrong, like your speakers might catch fire if you’re not careful. Then, just as quickly as it came, it recedes, but not entirely, hovering and menacing, barely audible behind the drums. You spend the rest of the track wondering: Will it come back? I won’t spoil it for you.

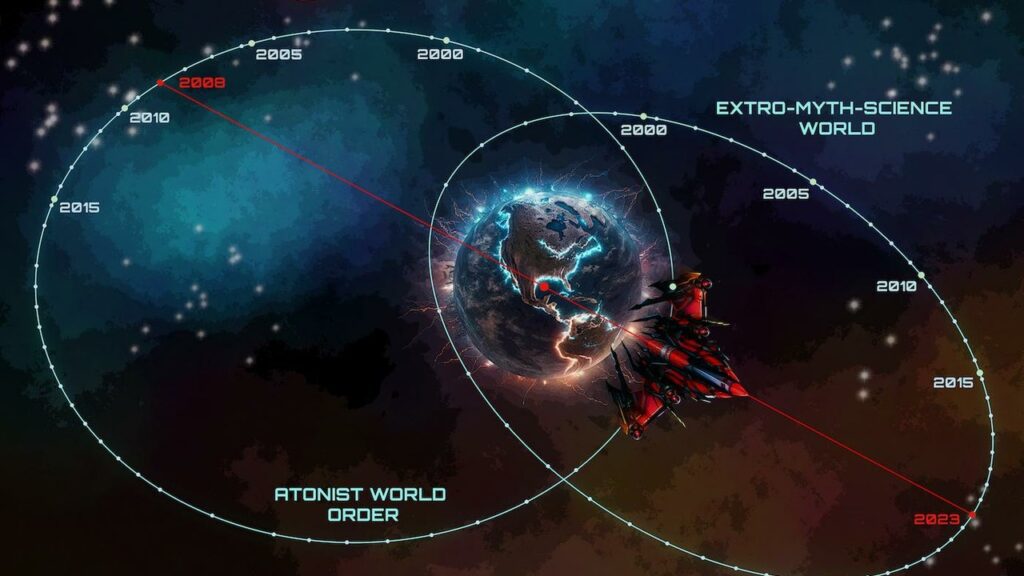

Techxodus doesn’t require deep knowledge of Brown’s work as a critic and historian in order to appreciate it, but it is a demanding album, unlikely to win over the club set. Given the polemical tone of Brown’s interviews and public appearances, I would imagine he prefers it that way. But the music isn’t antagonistic or standoffish; on the contrary, it wants to reach you, shake you, make you feel deeply. By sampling directly from free-jazz horn players on “Jes Grew” and opener “D.T.A.W.O. (Deprogramming the Atonist World Order),” Brown invites the comparison to that earlier rebellion against Eurocentric systems of rules that would enclose and govern Black art. It’s an apt one. Like those pioneers, he seeks to reconnect his music with its radical roots, and in doing so, push it toward the future.