About three-quarters of the way through One Night Stand! Live at the Harlem Square Club, the beat stops and Sam Cooke says he’s gotta tell us about his baby right now. Backed by drumrolls, clattering cymbals, and a swaying buzz of minor-chord guitar, Cooke is speak-singing, hoarsely, in a free-flowing cadence. He and his lover fussed and fought; she left; he feels so alone; and now he has to banter with a telephone operator before finally—finally!—he gets through to her. “I got a message for you, honey/I wanna tell you that darling you-u-u-u-uuuu, ohhhhhhh,” he roars, desperate and teasing. The crowd can’t stand it, erupts in shrieks; you can pick out individual voices. Smoke and booze hang in the sweaty Saturday night air. Cooke starts up again: “You send me.”

It’s a sly twist on Cooke’s first pop hit and only No. 1, “You Send Me,” originally released in 1957. At Miami’s Harlem Square Club, he bats the title around twice more, each time heightening the expectation he’ll switch into the familiar tune, each time also reminding us how far he’s evolved since then. Cooke doesn’t end up playing the rest of the song, but his howling entreaties make the mere promise of it feel like the entire world. When, right at the brink and without straying from his telephone story, he abruptly pivots into a different number, the 1950s are vanquished and the ’60s have definitively begun.

As a civil rights advocate and architect of soul music, alongside Ray Charles, Cooke is a towering figure in American history. After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Rosa Parks comforted herself by listening to Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come,” and its resonance has never waned since, from Barack Obama’s first presidential election victory speech to the funeral of George Floyd. The song has become foundational, and so is Cooke’s artistry as a whole, touching anyone who was ever influenced by soul: Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding on through to Beyoncé and Bruce Springsteen, Sexyy Red and Jonathan Richman, and many more in between.

And yet for someone whose legacy has become such a part of the cultural firmament, Cooke remains surprisingly mysterious. As a successful Black singer, songwriter, and businessperson—he co-founded his own label, SAR Records, at a time when that was rare for any artist—Cooke prefigured Prince and Michael Jackson. In 1986, he was one of the first 10 inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, alongside obvious shoo-ins like Elvis Presley. But even then, Rolling Stone misstated both the place and year of Cooke’s birth. Jerry Wexler, the Atlantic executive who coined the term “rhythm and blues,” told The New York Times that Cooke was “the best singer who ever lived,” but not before the same Times critic got Cooke’s home city wrong. Though he died in 1964, Cooke seems to somehow keep winning Grammys, including a lifetime achievement award in 1999, but his discography has hardly been given the retrospective attention of other industry titans from the era. His work is messy and alive, and fraught with existential contradictions.

In 1931, Samuel Cook was born in Clarksdale, Mississippi, the Delta blues birthplace at whose crossroads Robert Johnson purportedly sold his soul to the Devil. He was the fifth of eight children, carried by his mother on a Greyhound bus to Chicago while still a toddler. There, he started his singing career in his father’s church at the precocious age of 6, performing alongside his siblings as the Singing Children. At 16, he joined up with a local teenage gospel group, the Highway QCs. Three years later, he was invited to join the gospel circuit’s more established Soul Stirrers. At 26, he made his solo, secular debut—first unceremoniously with a one-off single as Dale Cook, and then, with an added “e” to seem “classier,” as Sam Cooke, with “You Send Me.”

In “You Send Me,” Cooke delivered a masterpiece of restraint, expressing the giddiness of new love with a breezy sophistication that kept any hint of romantic love’s usual erotic frisson concealed beneath the smooth surface. “You move me,” he sang, with the disarming politesse of Eddie Haskell, several years before the Troggs roughened the phrase on “Wild Thing.” A string of hits that still populate oldies stations, film soundtracks, and karaoke songbooks would follow, but there’s plenty of reason to wonder what could have been. As was typical of the pre-rock era, Cooke’s albums were often scattershot, at least until he won artistic control in late 1963. And even then, with an eye on the careers of the few other Black performers who had won over the era’s white audiences—especially jazz-pop trailblazer Nat King Cole and Cooke’s near-contemporaries like Harry Belafonte and Johnny Mathis—Cooke was not averse to supper-club schmaltz. Devastatingly, Cooke was shot and killed under disputed circumstances on December 11, 1964. In a posthumous insult, industry vagaries kept portions of his catalog languishing out of print for decades.

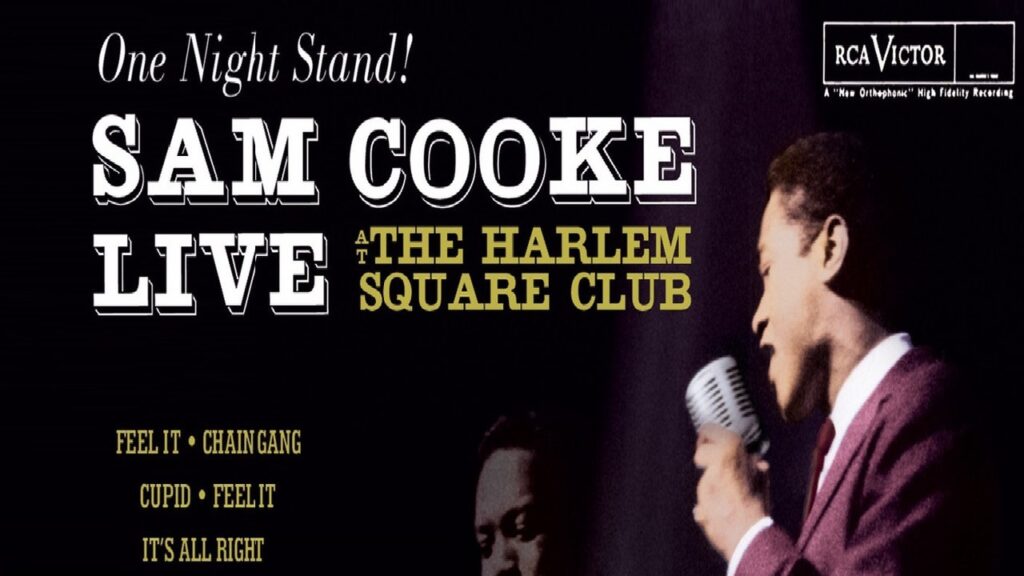

One Night Stand! Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963 is a monumental soul artifact, one of the greatest live albums of all time, and, in its defiant partying from the depths of the segregated South, a veiled precursor to the explicit activism of “A Change Is Gonna Come,” which wasn’t released as a single until after Cooke’s death. In a scant 10 tracks and 39 minutes, the album captures one of the most beguiling figures of 20th-century music as close to the peak of his powers as he was ever recorded, sounding grittier and more seductive than you’ll hear on those good-times oldies blocks but still every bit in command. Now, 60 years later, it’s a righteous celebration that collapses the decades.

Ahead of the performance that would end up on One Night Stand!, Cooke was in a fascinating flux. At the start of 1962, he was already the best-selling singles artist on RCA after Elvis. That October, while James Brown was in Harlem recording what would become his classic Live at the Apollo—and when nuclear tensions peaked during the Cuban Missile Crisis—Cooke was touring the UK with Little Richard, who dashed off for a Liverpool bill headlining above the Beatles. The appreciative reaction overseas helped encourage Cooke to incorporate more gospel fervor into a reworked set, which he debuted at the Apollo, complete with hanging-on-the-telephone “You Send Me” riff, on November 2. On the same Apollo bill was another soul luminary, saxophonist King Curtis, who Cooke cajoled into joining him on an upcoming Southern tour even though, as a revered session player, he could have made more money at home. Cooke closed out 1962 with a return to his roots, joining the Soul Stirrers onstage for New Year’s Eve.

At the same time Cooke was emphasizing gospel passion in his live music, he was becoming more politically engaged. He was poring over the poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar, the pioneering Black writer from the post-Reconstruction period. According to Cooke’s biographer Peter Guralnick, he was also “undoubtedly” reading a James Baldwin essay published in The New Yorker in November 1962. Alongside an urgent call to action, the piece, part of the writer’s enduring race-relations book The Fire Next Time, ends with a powerful assertion that Black is beautiful. Right before the tour with King Curtis, Cooke gave an interview urging his fellow Black stars not to forget Black weekly newspapers and magazines.

No one seems to remember how it was decided that two RCA engineers would be flown down to record Cooke’s January 12, 1963 performance in Miami. The Harlem Square Club was a 2,000-capacity building within the “Little Broadway” district of the segregated city’s historically Black neighborhood of Overtown. According to Newsweek, “Liquor was sold from a caged enclosure by a bartender armed with a shotgun.” The engineers set up their equipment—eight microphones and a three-track mixer—during a 4 p.m. matinee, adjusted it once the crowd exploded for the first evening show, at 10 p.m., and then gave up all hope of getting back to the stage before the late show, at 1 a.m., which would be immortalized on One Night Stand!.

It’s the strongest full-length Cooke ever laid to tape. His studio albums—even the best, August 1963’s wee-small-hours blues opus Night Beat and February 1964’s expansive Ain’t That Good News—were lavished with strings, choirs, and superfluous cover songs aimed at white swells with fat wallets. Live at the Harlem Square Club showcases a tight, guitar-driven band that King Curtis’ fiery sax takes to another level; Cooke’s vocals, while still as melismatic and controlled as ever, are gorgeously rough-edged. Aside from King Curtis’ introductory “Soul Twist”—a 1962 instrumental hit—and a wry rendition of the Nat King Cole standard “(I Love You) for Sentimental Reasons” that’s tucked away at the back end of a woozy medley, One Night Stand! is all Cooke originals. It’s an ode to spontaneity and evanescence that feels as elaborately plotted as a concept album.

In this setting, Cooke’s hits take on new life. After a few words from King Curtis and a friendly greeting from Cooke, “Feel It (Don’t Fight It)” sets out a pair of favored Cooke themes, the transcendent powers of good music and young love, at an uncharacteristically breakneck pace; even if you wanted to fight the feeling, you’d have to catch it first. “Cupid” arrives almost in quotes—“Maybe you remember this one,” Cooke begins, “a very nice little song, nice and sweet”—and accentuates the original’s Caribbean feel and stretches out the onomatopoeic “sss” when Cupid’s arrow goes “straight to my lover’s heart,” while Cooke’s chuckles drive home the irony that for all of the tragedies in his life, he surely never had to pray to a minor Greek love deity. Cooke livens up his dance craze tie-in “Twistin’ the Night Away,” here interpolated with part of Chubby Checker’s “The Twist,” by exhorting everyone to “take round” their handkerchiefs; his “take the, take the, take the” ad libs feel as jubilantly insistent as a Chuck Berry guitar lick.

Cooke’s interplay with the crowd also transforms the material. “Chain Gang” was always an unusual pop hit, with lyrics about forced, largely Black labor, and the propulsive Harlem Square Club version posits an alternative universe where the Clash covered this instead of “I Fought the Law.” But there’s a secondary type of release in a mass of people shouting “uhh” and “ahh” as Cooke purrs, “Oh yeah,” that seems more in line with the lusty grunts at the end of Fleetwood Mac’s “Big Love.” In a full-throated sing-along of “(I Love You) for Sentimental Reasons,” at least one woman’s voice stands out on its own, filling out the harmony. Other voices squeal. Not unlike Apollo 11, the 2019 moon-landing documentary using unreleased archival footage, it feels like you’re bearing witness to a key historical moment from an uncannily intimate perspective.

Part of the tension of One Night Stand! comes from Cooke’s purposefully sappy celebrations of love positioned alongside his real-world cynicism. The front end of the “Sentimental Reasons” medley is the Cooke original “It’s All Right,” a song of unconditional devotion that’s introduced as advice for men who hear that their lovers have been unfaithful—they should try a little tenderness, obviously. The second-to-last song of the set, “Nothing Can Change This Love,” seems like a swooning love song that’s all “cake and ice cream” in the lyrics, but Cooke’s cackling laughter, King Curtis’ yearning sax solo, and the band’s ragged minor chords emphasize the cracks in the studio original’s cool reserve.

Cooke’s deconstructed take on “You Send Me” follows another sweeping bit of self-mythologizing. On the bluesy “Somebody Have Mercy,” then his most recent song on the pop charts, Cooke sings about “goin’ down to the bus station”—his own autobiographical crossroads—and wondering if a “cotton-pickin’ matchbox” will hold his clothes (“Can you imagine me carrying one of them suitcases?” he asks the audience). At its core, it’s another song about lovesickness—“have mercy” in the Roy Orbison–Jesse Katsopolis sense—but in another ad lib, Cooke shoots down an urban legend circulating at the time: “It ain’t that leukemia, that ain’t it,” he deadpans. He soon chuckles, but the need to respond to a “Paul is dead”-level conspiracy theory is an indication of the pressures confronting a gospel-turned-pop star, two weeks shy of his 32nd birthday, long before the 24-hour news cycle. The live version, with another standout King Curtis solo, vastly improves on the studio cut, but the closing lyric would be malapropistic brilliance in any incarnation: “I got such a long way to get there/And such a short time to go,” Cooke sings. It doesn’t make sense, but the dissociated feeling resonates through the ages.

One Night Stand! crests—as does, arguably, Cooke’s entire career pre-“A Change Is Gonna Come”—with an incredible rendition of “Bring It On Home to Me,” then a recent non-album single and Cooke’s most gospel-charged solo side to date. “This song gon’ tell you how I feel,” Cooke begins, and he doesn’t let the audience down; if you listen closely, you’ll hear a thumping sound that can only be Cooke pounding his chest. The band is raucous, Cooke exudes joy, and the crowd sings along like it’ll keep the lights from going on, Cooke from leaving, them from having to go home to 1963 reality. Cooke recognizes it, too: “Everybody’s with me tonight!”

As critic Hilary Saunders has written, One Night Stand! throws “the party of the century on the eve of destruction.” Six months after its recording, Cooke’s 18-month-old son died in a drowning accident. In October, Cooke was turned away from a Shreveport, Louisiana, hotel in the events that inspired “A Change Is Gonna Come.” The following February, again in Miami, he met with Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. By the end of 1964, Cooke was gone.

Before Cooke’s passing, he did release one live album, 1964’s Sam Cooke at the Copa, a slick set so Las Vegas-ready that it’s introduced by Sammy Davis Jr.; one jarring highlight is a hepcat-paced “Blowin’ in the Wind” cover. Cooke’s manager prior to his death was Allen Klein, the infamously pugnacious impresario who later feuded with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and that fact seems to partly explain why One Night Stand! sat in the vaults until RCA brought in a new head of A&R in the mid-’80s. Indeed, several of Cooke’s albums were long out of print, including the album with “A Change Is Gonna Come.” When this live set was finally issued in 1985, as Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, amid a spate of archival soul releases, critics took notice, sending the 22-year-old recording to No. 11 on the Village Voice’s 1985 Pazz & Jop poll.

Although Leslie Odom Jr. gives an emotional performance as Cooke in a 2020 film, One Night in Miami…, dramatizing the 1964 encounter with Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X, there may be a reason that no one has yet made a biopic about Cooke alone. His lofty mission, combined with the brutal indignities of Black stardom in ’50s and ’60s America, meant that he was constantly recalibrating, his innermost thoughts tucked away deep: a soul cipher. He was complicated. Even to his intimates, Cooke was, as biographer Guralnick wrote, “someone who could mask everything but his ambition.” As a little boy, he pretended popsicle sticks were his audience. By the time he was 9, he told his brother he was never going to work a regular job, just sing and get rich. In one of his final interviews, he spoke earnestly of his “intense desire to make all of my audiences happy.” He also offered an inscrutably open-ended definition of soul: “the capacity to project a feeling.”

In 2000, another version of the Harlem Square Club recording was released as part of the box set The Man Who Invented Soul. If this was your introduction to these performances, as it was for me, you missed out for years on much of the crowd noise that helps make the music feel so alive. The audience’s rowdy presence was restored in a 2005 remaster, which revived the original “One Night Stand” working title, swapped in new cover artwork that shows King Curtis, and is widely available on streaming platforms. If Cooke’s purpose in life was “wooing the world,” as The Independent put it, One Night Stand! is the album that can still pull it off.

Cooke recognized early on that Bob Dylan would draw a crowd not for the way that he sang, but for the message in his words. In January 1963, for Cooke, performance was still more gestural. One Night Stand! ends not with a protest song, despite the tumultuous times, but with a manifestation of communal joy that the powers that be couldn’t take away. The song is the featherlight yet floor-stomping soul groove “Having a Party,” which neatly bookends the album by name-checking King Curtis’ set-opening “Soul Twist” and then adds yet another perfect Cooke lyric: “The Cokes are in the icebox,” he sings, recognizing the poetry in the details of everyday mid-century existence. The mood is euphoric, shaky, the right amount of too much.

“I gotta go, but when you go home, keep on having a party,” Cooke announces at last, in a farewell that feels like a benediction. “If you’re with your loved ones somewhere, keep on having that party. If you feel good all alone riding with the radio some time, riding in a car and the radio is on, keep on having that party.” As “A Change Is Gonna Come” ascends to its sacred place as a national hymn, Live at the Harlem Square Club stands as a reminder that somewhere in between too-hard living and fearful dying—who knows what’s up there beyond the sky, anyway?—we surrender ourselves to Saturday night. Cooke told us how he felt, and now everybody is with him.