When Pink Floyd first premiered what would become the most successful rock album of all time, it was quite literally too big for the system to handle. A half-hour into the band’s concert in Brighton on January 20, 1972—the live debut of what was then called “Eclipse: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics”—the band started to play “Money,” which required synchronizing their performance to a pre-recorded sound collage of jingling coins and ka-ching-ing cash registers. But coupled with the band’s power-sucking sound system and lighting rig, the show slowly ground to a halt. After a brief break, bassist Roger Waters came to the mic to explain: “Due to severe mechanical and electronic horror, we can’t do any more of that bit, so we’ll do something else.” Less than a month later, the band had to abandon a performance at the Manchester Free Trade Hall when the same thing happened.

Over the prior half-decade, Pink Floyd had established themselves as, if not the best psychedelic rock band, then certainly the most technologically extravagant. From late 1966 through the fabled Summer of Love, they were the house band at the UFO, the Swinging London rock club/art space/drug den, which gave them free rein to blend their droning jams with trippy visuals, sound effects, fog machines, and extreme volume. That August, Waters told Melody Maker that he wanted Pink Floyd to travel from city to city with a circus-style big top. “We’ll have a huge screen 120 feet wide and 40 feet high inside and project films and slides.”

His prediction never came to be, but for an invite-only gig at Queen Elizabeth Hall in May 1967, the band installed a joystick dubbed “The Azimuth Co-ordinator” on top of Richard Wright’s keyboard to send the band’s potent, droning sound and sci-fi effects careening around the first-of-its-kind quadraphonic playback system in the venue. For the back cover photo of the 1969 double album Ummagumma, drummer Nick Mason arranged the band’s road gear to resemble an aircraft carrier, a concise reversal of one philosopher’s claim that rock music is not much more than “a misuse of military equipment.” Waters told Melody Maker that Pink Floyd’s gear fixation was a matter of going where no band had gone. “We’re trying to solve problems that haven’t existed before.”

So, too, was NASA, whose decade-long effort to put men on the Moon was coming to fruition at the same time. It was a perfect match: Around 10 p.m., Pink Floyd appeared on the BBC’s marathon telecast of the Apollo 11 landing and jammed on a song they called “Moonhead.” Along with the requisite panels of astronomers and physicists, the quartet was joined by space-themed poetry readings from Ian McKellen and Judi Dench, and recordings of Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra”—prominently featured in Stanley Kubrick’s sci-fi opus 2001: A Space Odyssey—and the new single “Space Oddity,” released to capitalize on moon mania by ambitious 22-year-old folkie David Bowie.

Though Bowie was just beginning to explore the cosmos, Pink Floyd had been traveling the spaceways since their inception: The first track on their debut album was “Astronomy Dominé,” a slab of B-movie sci-fi cheese masterminded by the band’s co-founder, songwriter, and frontman Syd Barrett, which, along with “Interstellar Overdrive,” landed them the “space rock” sobriquet from critics. Though no band likes to be classified so generically, they grew to embrace the idea. Eighteen years later, the band’s official tour t-shirt read “Pink Floyd: Still First in Space.”

Barrett watched the moon landing at his Wetherby Mansion flat in London with a group of friends and hangers-on. By 1969, Barrett had disappeared into a haze of quaaludes and LSD that eroded his already-fragile mental health. There was a depressing irony in the fact that Barrett had churned out the whimsical art-pop character studies “Arnold Layne” and “See Emily Play” that got the group signed by EMI, then immediately soured on the non-stop promotional requirements that came along with hit singles. When Barrett showed up to live gigs in 1967, he was more of a distraction than a contributor. Forced to lip-sync on TV, he barely moved.

The band hired Barrett’s childhood mate David Gilmour as a live replacement, and one day they simply headed to a gig without picking up their singer. While Barrett was a master of making quotidian things charmingly weird, Roger Waters—who’d become Pink Floyd’s leader by dint of his forceful personality and big ideas—was honest about his careerist impulses and grand aims. “That was always my big fight,” Waters later said, “to try and drag it kicking and screaming back from the borders of space, from the whimsy that Syd was into, to my concerns, which were much more political and philosophical.” It would take a half-decade after splitting with Barrett for Waters to reroute his obsession with outer space into a grand treatise on—as he’d later call it—inner space.

In the five years between Barrett’s departure and the 1973 release of The Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd wandered the hinterlands as European psychedelia fractured into the high-minded progressive rock of the Moody Blues, the Nice, Procol Harum, Yes, King Crimson, and Jethro Tull; the jazz-fusion experiments of John McLaughlin and Soft Machine; the rock-operatic pretensions of the Who and Genesis; fellow space-rock travelers Hawkwind; and the synth-obsessed German bohemians Kraftwerk, Neu!, Tangerine Dream, and Popol Vuh. Without their putative leader and most charismatic member, Pink Floyd recorded a string of low-budget film soundtracks, released the classically gassy concept albums Ummagumma and Atom Heart Mother, helped Barrett record his 1970 solo debut Madcap Laughs, and toured the world. They earned enough money from their elaborate live shows—which journalists were beginning to describe in terms of tonnage—to make up for their paltry album sales.

With 1971’s Meddle, the band finally settled into a studio groove. The best of the new songs was the side-long “Echoes,” over 20 minutes of airtight studio jamming, a bit of jazz and folk, a single, repeating piano note fed through a Leslie speaker, and Waters’ newfound lyrical focus on the riddles of social alienation. Gilmour and Wright’s serenely harmonized voices intone Waters’ lyrics: “Strangers passing in the street/By chance, two separate glances meet/And I am you and what I see is me.” This recognition of a stranger’s shared humanity and pessimistic view that empathy is an impossible thing to communicate was rooted in Waters’ regret at being increasingly unable to reach his friend Syd. But as “Echoes” demonstrated, that fear could be blown out to galactic proportions.

There’s a good chance that Waters was among the billion or so humans who first saw the far side of the moon on Christmas Eve 1968, when Apollo 8 beamed the first detailed images of the mysterious lunar surface to televisions around the world. As astronomers have stressed for decades, “far side” is the accurate scientific term, but the spooky indeterminacy of “dark side” allows everyone else to tap into the same stoned undergraduate awe of learning that “lunatic” is derived from the 13th-century notion that some forms of mental illness were caused by adverse reactions to the moon’s phases. For Waters, the dark side of the moon was an inaccessible psychic space to which Barrett had retreated, perhaps forever, ingesting immeasurable amounts of psychedelics to cope with the unbearable stresses that accompany life on Earth, let alone one lived in the luminous glare of the public eye.

On the penultimate Dark Side track “Brain Damage,” he leads the band on a quest to find their wayward friend. There are elements of old Floyd on the verses: Gilmour alternates between major and minor chords, Waters sings of creeping madness like a seance leader while a man’s deep voice emits a maniacal haunted-house laugh. But on the choruses, the band soars skyward into a gospel-rock echo of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and “Let It Be,” with Waters making an even grander attempt toward cosmic connection: “And if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes/I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon.”

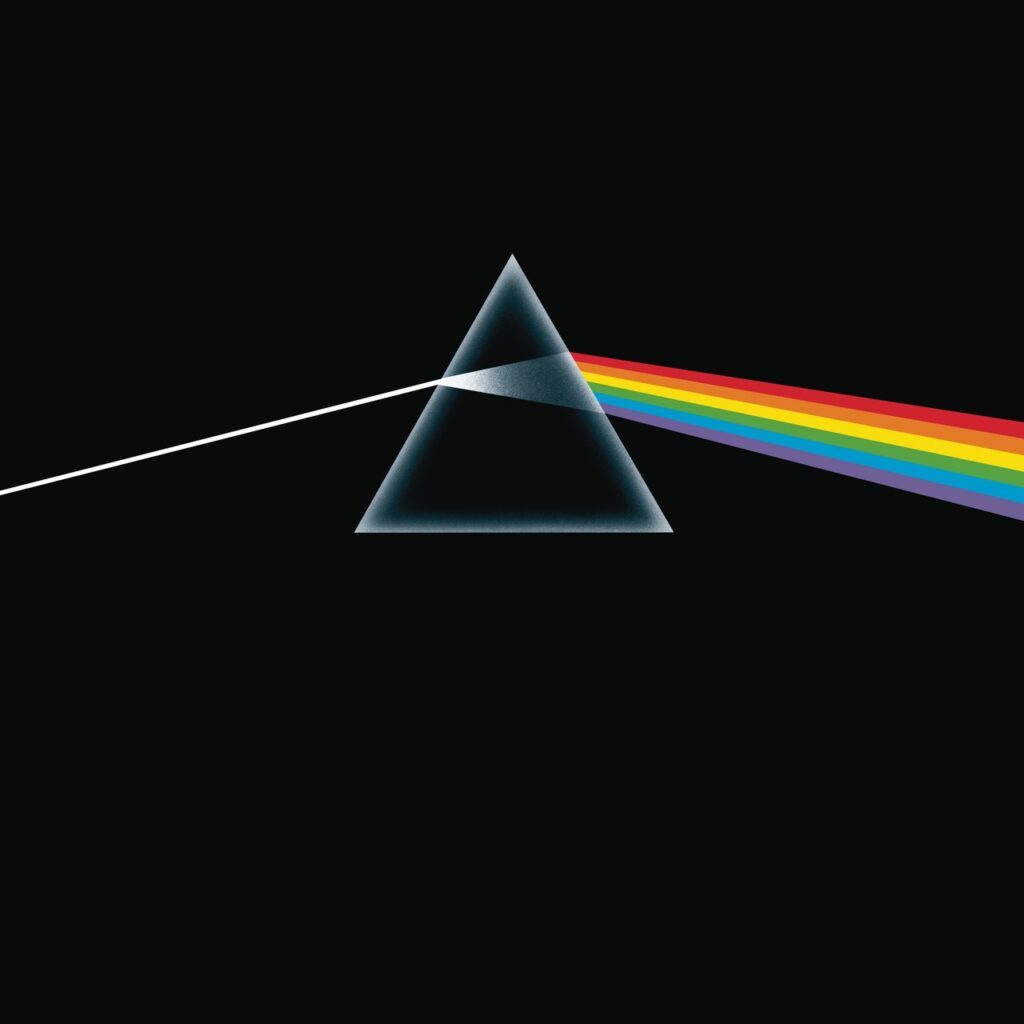

Pink Floyd’s expansion of the interpersonal to the intergalactic materialized at a moment when the record industry was more than ready to accommodate it. Waters’ ambition toward art-rock as gestalt—records, packaging, films, and concerts combined into an overwhelming whole—accelerated the rapid growth of the rock-industrial complex of the 1970s. In 1972, Pink Floyd introduced Dark Side’s songs in 3,000-capacity theaters. By 1975, they and their arena-rock contemporaries were playing 60,000-seat stadiums. Like the post-Sgt. Pepper’s Beatles, Led Zeppelin, and many of their prog peers, Pink Floyd viewed the album as the paragon of rock meaning, and Dark Side is the culmination of rock’s transformation into sacred druggie ritual and the elaborately packaged rock album’s transmutation into a rockist totem, a bearer of secrets, something to be decoded. With the help of their Cambridge friends Aubrey Powell and Storm Thorgerson of design firm Hipgnosis, the Dark Side album’s prism-on-black design ushered in a new era for rock iconography, as stark and suggestive as 2001’s obelisk.

The Dark Side of the Moon is by just about any measure rock’s most overdetermined album: It can be hard to talk about the music itself, and not the stats and legends accreting around the eighth-highest-selling album of all time. The music’s sense of scale and gravity communicates importance, but 741 consecutive weeks on the album chart is something else entirely. Dark Side’s unhurried tempos and swells of emotion are grandly cinematic, and the band maintained mystery by avoiding the press, but that’s true for lots of bands that don’t generate widespread conspiracy theories about secretly composing their music to sync up with The Wizard of Oz. In truth, Dark Side’s music didn’t sound much like Pink Floyd’s previous work, and went places that firmly separated the band from its peers. Few 1973 bands were blending rock with jazz, sound montages, electronic sequencers, and interviews with average people about their deepest fears and secrets. Overwhelming earnestness and statement-making are tough for a band to pull off at the same time, and attempts at making profound alienation sound beautiful that aren’t Dark Side or OK Computer inevitably fail.

Though Waters himself has described Dark Side’s theme as a simple battle between darkness and light with outer space as a backdrop, he’s actually underselling the album’s elegant doomerism—apropos of, well, everything that was happening at the time. Some light bleeds through, but not much. From the moment your lungs draw air your innocence is lost, and your life is spent fighting against the forces of time, money, religion, death, and politics, culminating in a sizable psychic (“Brain Damage”) and existential (“Eclipse”) collapse. If the real subject of English psychedelia, as the Beatles’ chronicler Ian Macdonald has it, is neither drugs nor love, but the lost innocence of childhood, then The Dark Side of the Moon could reasonably be called the end of the 1960s countercultural dream. The vivid spectrum of refracted light surrounded by depthless pitch black. The sun is eclipsed by the moon.

Dark Side was the No. 1 album in the U.S. for a week in April 1973, pushed to the top by incessant FM radio airplay of the single “Money.” Preceded by the same coin-and-cash register montage that melted down their 1972 Brighton concert, Waters’ spongy introductory bassline marks a tonal shift in the album’s mood and flow. Even with the necessity of a side-flip between tracks, the decision to follow the orgasmic death-wail of “The Great Gig in the Sky” with the crass sounds of commerce counts as the album’s lone wanly humorous moment. In interviews, Gilmour has implied that he took Waters’ demo as an opportunity to make a kind of prog-rock “Green Onions,” but the closest comparison to a blues in 7/4 with a sarcastic lyric about grotesque greed, complete with a fiery sax solo and a three-part guitar solo, was Steely Dan’s July 1973 single “Show Biz Kids” (the following year, the O’Jays would issue the definitive take, with the definitive bassline, on the topic).

Though Pink Floyd had to be talked into even releasing “Money” as a single, the programmers in the Album-Oriented Rock radio format wouldn’t have minded either way. The most successful new format of the decade, AOR was a corporatized, data-driven update of the late-’60 “free-form” model of radio programming. Free-form merged the anti-establishment tenor of the era with the FM band’s sonic superiority over AM (the home of transistor radio-friendly Top 40) to merge political progressivism and progressive rock, eschewing standardized playlists and constant advertisements in favor of the Ummagumma version of “A Saucerful of Secrets” and plugs for local head shops and third-party candidates. But in the same capitalist metamorphosis that turned field festivals into arena shows, AOR engulfed free-form, replacing the DJ’s ear with demographic research and point-of-sale polling. Rock album sales exploded: Apart from Dark Side’s week at No. 1, 39 weeks of 1973’s Billboard 200 album chart were topped by AOR-programmed acts: the Moody Blues, Alice Cooper, Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, Wings, George Harrison, Chicago, Jethro Tull, the Allman Brothers Band, the Rolling Stones, and Elton John.

That list underscores two effects of the AOR revolution: the final cleavage of (white) “rock” from (Black) rock’n’roll, R&B, funk, and soul; and AOR’s blatant preference for music made by men. One of Dark Side’s greatest tricks is making sure that suburban stoners could find their way into songs like “Money” or “Us and Them” through their countercultural aura, while Wright’s modal jazz tints, Gilmour’s tone, and Parsons’ lush quadraphonic engineering could just as easily rope in the “high-fidelity first-class traveling set” of pseudo-cosmopolitan Playboy readers (who voted it third in their 1973 Jazz and Pop poll in the “small combo” category, behind Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Birds of Fire and Jethro Tull’s A Passion Play).

During production, Waters advocated for a drier sound, and more intense psychological exploration inspired by Plastic Ono Band, an idea that was thankfully nixed in favor of what Gilmour called a “big and swampy and wet” mix. “Breathe,” “On the Run,” and “Time” are the exemplars of this approach, forming the sonic and theoretical core of the album’s Side A. “Breathe” dramatically blooms into existence out of the album’s opening sound collage with Gilmour’s placid Fender 1000 twin neck pedal steel at the fore. Though the steel guitar was a mainstay in Jerry Garcia’s country–rock arsenal at the time, Gilmour’s open-G tuning hewed closer to the languid tones of the Hawai’ian islands where it was born. Combined with the vibrato effect of the Uni-Vibe pedal on his Stratocaster, the track is both impossibly tranquil and gently unnerving. The recommendation to simply “breathe” can be said to someone giving birth, meditating, or having a panic attack or bad trip, and Waters moves the story quickly through the beginnings of life through an existence marked by tireless labor, then a premature death.

When Pink Floyd entered the studio in May 1972, they’d road-tested their new material for a year; the songs were all fairly far along, leaving ample time for production and experimentation. On Meddle and the Obscured by Clouds soundtrack they recorded in France a few months prior, they’d deployed one of Wright’s new gizmos: a synthesizer and primitive sequencer made by the English company EMS Synthi-A that he had bought from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. They were all the rage in 1973—John Paul Jones fed his piano through one to create the eerie mood of Led Zeppelin’s dirge “No Quarter” and Brian Eno used one on the Roxy Music song where Brian Ferry sings about having sex with a robot. For Waters, however, the Synthi’s eight-note sequencer generated an inhuman, hyper-modern sound-swirl that, when mixed with the recorded sounds of airport terminal announcements, mimicked the intense travel panic that he was increasingly experiencing as a touring musician. Life as he saw it was not a matter of wrangling modern technology toward a sunny future, like Kraftwerk a year later, but a numbing cycle of alienated labor and idle, wasted moments.

Introduced with its own two-minute overture that moves from Parsons’ clock-sounds montage and Nick Mason’s roto-tom solo, “Time” is Dark Side’s grooviest and simplest song, with Gilmour’s taut riffs backing Waters’ best set of lyrics—a far more serious take on the sardonic Kinks-glam of Obscured’s “Free Four.” About as close to a Marxian statement on industrial capitalism as one could hear on FM radio, “Time” combines with “Breathe” to evoke Marx’s well-traveled claim that capital’s institution of tight factory clock regulations caused a psychic rupture in the human understanding of time, and a took a physical toll on our bodies. When you are young and time is long, your days are occupied “killing” time, but as you age, you increasingly focus on “saving” and “spending” it—until, all of a sudden, it runs out. “Time” gives way to a brief “Breathe” reprise introducing the opioid effects of softly spoken magic spells.

Titled “Religion” in its demo form, “The Great Gig in the Sky” initially took shape as a cyclical Wright-led instrumental with Gilmour accompanying on pedal steel, but the band made the last-minute decision to add a female vocal to the track. They called in Parsons’ acquaintance Clare Torry, a local session singer who came into the studio cold, and was prompted by Gilmour and Wright to, she recalls, improvise over the track while imagining a “birth and death concept.” She nailed the album’s ecstatic emotional peak in a few takes. In the context of Dark Side, “The Great Gig” feels like a transitional point—in musical flow and skyward narrative ascent—but AOR programmers extracted and rotated it regardless. In the right sequence—say, near Merry Clayton’s powerhouse choruses on “Gimmie Shelter” or Jim Gordon and Duane Allman’s elegiac piano-and-slide coda to “Layla”—it slotted in perfectly.

So did “Us and Them,” the album’s best song, which gently moves through Wright’s modal chord changes and highlights the album’s soulful backup quartet (which included Doris Troy, who’d co-written her own hit a decade earlier, and had provided vocal punch for the rollicking coda of “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”). The seductive music is a feint, of course, softening the blow of an evocative and elemental Waters sentiment about the cruel abstractions of war. Waters’ father was a schoolteacher and member of the Communist Party who, after initially refusing to join the Army in lieu of volunteering closer to home, decided to join the 8th Battalion Royal Fusiliers as a second lieutenant. He died on the beaches of Anzio when Waters was five months old. Thirty years later, “Great Gig” and “Us and Them” cycled through the FM airwaves, providing a doleful backdrop for the senseless, state-sponsored murders slowly concluding in the dense jungles of Vietnam.

The Dark Side of the Moon remains Pink Floyd’s greatest musical achievement, and despite the band releasing four more albums before dissolving a bit more than a decade later, sent an early signal of its demise. Waters was growing ever more certain of his singular genius and forcing his will, while Gilmour and Wright resented his lack of musical chops and production choices in the studio. When the band split after 1983’s The Final Cut, Waters and Gilmour released solo albums within a month of each other, and toured separately while performing the same Dark Side songs. Waters’ new band (including Squeeze’s Paul Carrack on vocals) was still capable of booking arenas, but Gilmour, Wright, and Mason, as Pink Floyd, staged the highest grossing tour of the 1980s. Leave it to Pink Floyd to generate quantum versions of its original self.

In a 1987 Rolling Stone feature pegged to the release of the first post-Waters Floyd LP Momentary Lapse of Reason, David Fricke interviewed the ex-bandmates separately, surfacing just how much Gilmour resented Waters’ megalomania, which had driven Wright out of the band during the tense 1979 Wall sessions, and paraphrasing Waters’ characterization of the remaining Floyd members as “lazy, greedy bastards hacking out a record and sleepwalking through a tour to build up a multimillion-dollar retirement nest egg,” using, in Waters’ words, “the goodwill and the name Pink Floyd.”

By the time of Pink Floyd 3.0’s 1994 Division Bell world tour, the band was a cultural institution and had long been recognized as a formative cog in the same globalized, financialized record and touring industry that they used their music to decry. In Europe the tour was sponsored by Volkswagen, which released a “Pink Floyd Edition” Golf in commemoration. Such a tacky corporate tie-in may have caused a younger Waters to retch, but Gilmour—who’d recorded much of his post-Waters music on his posh houseboat—defended his affluence matter-of-factly in a 1995 interview: “When you compare [my wealth] to what chairmen of big companies earn, I think that I am more entitled to my millions than they are. After all, I have made the world happier than Unilever.”

The second set of each Division Bell date featured Dark Side played in full, and the tour was the largest-grossing in history before the Rolling Stones’ Voodoo Lounge trek eclipsed it the same year. When it came to Indianapolis’ Hoosier Dome in June 1994, a high school senior named Charlie Savage drove down from Fort Wayne with some friends to see one of his favorite bands for the first time. A few months later as a college freshman, Savage availed himself of his university’s internet connection to explore Usenet—a messageboard predecessor to the World Wide Web that contained information and discussion about thousands of topics—and quickly dove into alt.music.pink-floyd. There, he learned about a DIY multimedia ritual that Floyd fans had concocted, likely by stoned accident: synchronizing the CD version of Dark Side (which didn’t have to be flipped over) with the VHS version of The Wizard of Oz. At numerous moments, the music seemed to perfectly soundtrack the film’s action, inspiring speculation about whether the band had secretly intended it that way. The next summer, Savage wrote a piece about the phenomenon for his hometown Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette during an internship (Pink Floyd didn’t return several faxed requests for comment), and once he reposted it online, it went mid-’90s viral. By 2000, TCM paired with Capitol Records to program it.

While there’s no truth to the rumor, the “Dark Side of the Rainbow” myth does provide bold evidence for two dimensions of Pink Floyd and Dark Side. First, its omnipresence. Despite being one of the 20th century’s most recognizable works of popular culture, Dark Side has never ranked highly on any of Rolling Stone’s canon-creating album lists: It came in at No. 35 on their 1987 20th-anniversary Top 100, dropped to No. 40 on the 2003 Top 500 and slid to No. 55 on the 2020 edition. But it kept selling and selling and selling, only dropping off the bottom of the Billboard 200 in 1988—fittingly, the year after its home format, the vinyl LP, was outsold by its successor, the compact disc. The solemn, rockist vinyl rituals that Pink Floyd helped initiate with Dark Side were reimagined for the era of CDs, VCRs, and urban legends spreading online. It says something that Savage has won a Pulitzer Prize for his political reporting but still receives more questions about his college Floyd piece.

The second thing that “Dark Side of the Rainbow” highlights is that Pink Floyd is perhaps the classic rock band for whom the descriptor “cinematic” not only rises above cliché, but feels absolutely necessary. Their career started, after all, playing at the London Free School and UFO Club with synchronized imagery that engulfed them. Though they declined Stanley Kubrick’s request to use “Atom Heart Mother” in A Clockwork Orange, the methodical pace, overwhelming seriousness, precision-tooled production, and obsession with man/machine dynamics of Dark Side and its follow-up Wish You Were Here are deeply Kubrickian. “Breathe” was originally written as part of the soundtrack to the 1970 Vanessa Redgrave-narrated documentary The Body, and Michelangelo Antonioni rejected Wright’s “Us and Them” instrumental for a riot scene in Zabriskie Point. In 1973, an Australian filmmaker commissioned “Echoes” for a legendary surfing film, and for part of their 1974 tour, Pink Floyd commissioned several animations and short films to project on giant screens behind the stage. Though it’s true that any music played under any motion picture will inevitably synchronize somehow (“Echoes” over the end of 2001 works decently), it also makes perfect sense that this particular conspiracy attached itself chiefly to Pink Floyd.

The full Pink Floyd reunited for the London portion of Live 8, Bob Geldof’s 2005 sequel to Live Aid. Taking the stage between sets by the Who and Paul McCartney was a fitting end to a live career that began in Swinging London with must-see psychedelic multimedia spectaculars that both McCartney and Townshend popped in on. Waters and Gilmour were diplomatic and agreeable on stage—though Gilmour later said it felt like “sleeping with your ex-wife”—and they ran through “Breathe,” “Money,” and “Wish You Were Here,” Waters’ tribute to his long-lost friend Syd Barrett, whom Waters acknowledged from stage. Barrett died at his parents’ home a year later.

Like its predecessor, Live 8 was based on the notion that rock stars could save the world by staging a large enough spectacle. In 1985, at MTV’s early peak, that idea wasn’t yet as quaint as it would seem in 2005, long after rock stars had ceded the cutting edge of cultural and political conversation to subsequent generations and new technological infrastructure. In 2020, Gilmour and Mason reformed Pink Floyd for a one-off charity single, “Hey Hey Rise Up,” to support Ukraine’s battle against a Russian invasion, but it came and went without much fanfare. Waters, on the other hand, enters political debates with a vengeance, and with the kind of “freethinking” contradictions that suggest deep YouTube rabbit holes. In Waters’ mind, support for Palestinian independence and disdain for Donald Trump share space with anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, his desire to perform in SS-style uniforms in Germany, and his both-sides view of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Where he once barked at his ex-bandmate in the pages of Rolling Stone, Gilmour and his wife, writer Polly Samson, lit Waters up on Twitter.

Over the past few years, Merck Mercuriadis, the avaricious industry veteran, has spent billions buying up the publishing rights to dozens of Pink Floyd’s classic rock contemporaries and others, naming his firm Hipgnosis in tribute to the Dark Side designers. Waters himself has decided to expand the Dark Side franchise, re-recording its songs in new arrangements, ostensibly pegged to the album’s 50th anniversary, but also, one suspects, so that he can reap the profits from what one might call “Money (Roger’s Version).” And though the music and fanbases are different, trace backward in time from Taylor Swift and Beyoncé’s blockbuster 2023 stadium tours and you’ll find Dark Side-era Floyd hiring the Bond films’ effects coordinator and filling multiple semi-trailers with their amps and lighting rigs. Pink Floyd’s era of the rock star guru gave way to multiple waves of larger-than-life icons decades ago, but any performer-mogul bent on building impossibly huge and expensive musical experiences to call the faithful to their knees is, to some degree, working from The Dark Side of the Moon’s original text.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.