In Sam Greenlee’s 1969 novel The Spook Who Sat By the Door, protagonist Dan Freeman is a Black revolutionary moonlighting as a CIA agent, hellbent on protecting himself and his people from a world on fire. The author described the book as part Civil Rights Era satire and part “training manual for guerrilla warfare,” and its portrayal of revolution as salvation is as relevant now as it was 54 years ago. With it, Greenlee aimed to inspire Black readers to take action, “rather than always reacting as victims of a racist society.”

These kinds of well-intentioned but flawed sentiments, which place more blame on the individual than the system built to keep them down, have been connecting deeply with Killer Mike these days. The Atlanta rapper’s resurgence as one-half of Run the Jewels alongside El-P in the early 2010s amplified his already potent sociopolitical consciousness to superhuman levels. Those records were equally fun and confrontational: loose but always focused on raging against the racial and economic injustices of the world and forging a path ahead.

During Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016, Mike’s spirited battle cries captured so much of the country’s discontent. On “Thieves! (Screamed the Ghost),” from Run the Jewels 3, he rapped, “You can burn the system and start again.” A few songs later, he emphasized the importance of redistributing wealth to sex workers. At the same time, he was taking that radical spirit into the real world, building community-minded businesses and organizing food drives, among other initiatives. RTJ albums, especially the third and fourth ones, didn’t just foreground the kind of revolutionary anger and civil disobedience found in Spook—they gave it a modern urgency and a sense of direction.

But in the years since, Mike’s fiery raps have gradually taken a backseat to some less-than-ideal optics. He went from endorsing Bernie Sanders for president to taking an interview with NRA TV to having an inopportune meeting with Georgia’s Republican governor. Like the protagonist of Greenlee’s novel, Mike sees himself as a leader offering his people tools in a world stacked against them. But from another angle, it appears as though he’s doubling back, more content to work within the system than rail against it. It’s a familiar arc for so many who spend their lifetimes fighting for social change. When the landscape shifts and you start to lose touch, it’s easy to dig your heels in.

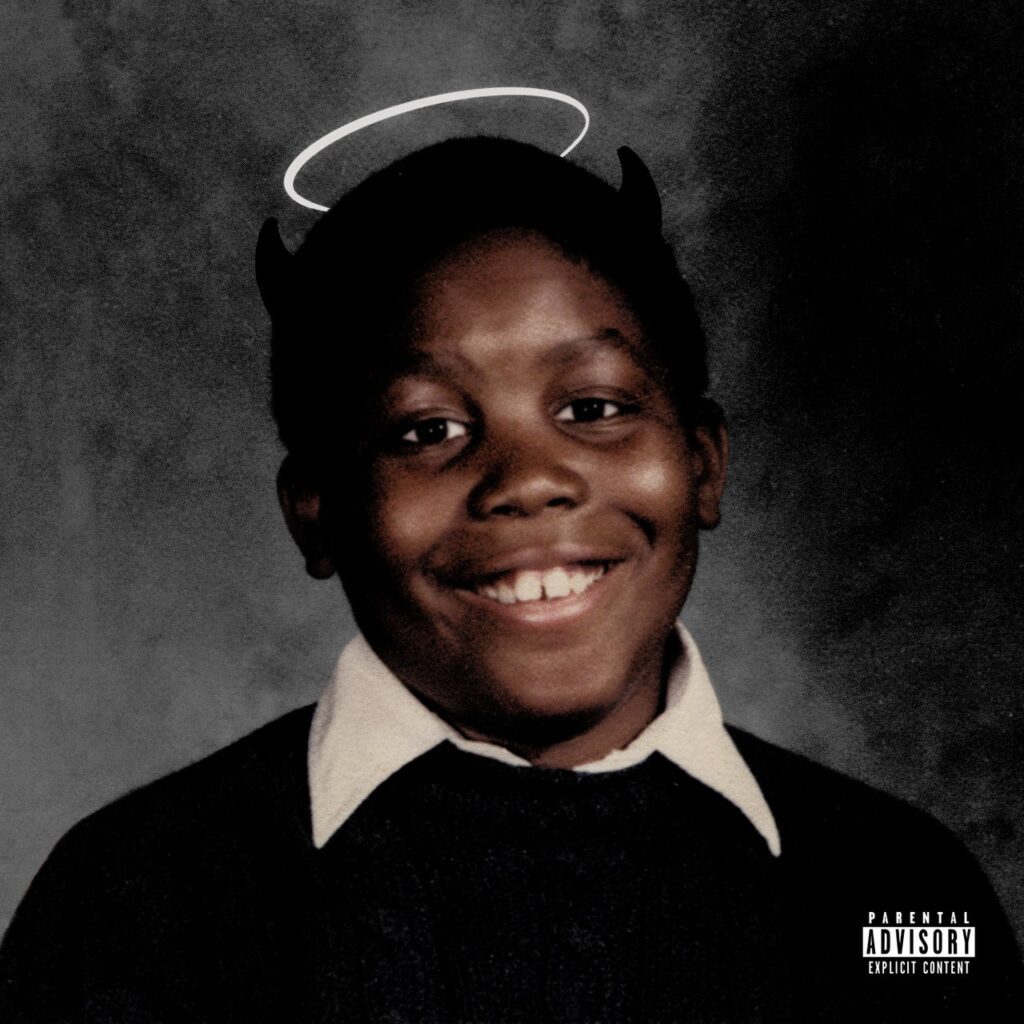

His latest album Michael—his first solo record since 2012’s R.A.P. Music—centers these conflicts and closes the gap between Killer Mike the rapper and Michael Render the husband, father, son, and born-again child of God. At its heart, Michael is an origin story that works best when it examines how worshiping at the altars of sex, money, and Jesus created the man we know today. But when he petulantly doubles down on critiques of his public persona and status as a Black multi-millionaire, the album is harder to stomach.

Rap music exists in a complex web of capitalistic deification and stacking bands as a survival tactic, but Mike’s worst takeaways often contradict one another without a thematic payoff. It’s unfortunate to hear him rap about his days living off drug and minimum wage money on “EXIT 9” on the same album where he calls others in similar positions lazy (“Too many y’all niggas laid up/And that’s why y’all niggas laid off” on “SPACESHIP VIEWS”). Occasionally, nuance gets cast aside for snide finger-wagging. “You still talkin’ New Jack City, that’s why you niggas poor,” he says pointedly on “NRICH,” making lengthy arguments about investing in real estate and his own Greenwood banking platform. Three songs later, he’s bragging about using tour money to buy a new Benz. Generating income for your family and community is a wonderful thing, but there’s a difference between aspirational hustler music and judgmental pocket-watching. Not only does this dissonance feel very “old rap man yells at cloud,” by indulging his preachier side, it often sabotages the balance Michael is so keen on maintaining. Mike wants us to see him as both a human being and a superstar, but the further the album strays from genuine self-reflection into sour disapproval, the worse it gets.

In a recent video posted to Twitter, Mike mentions a friend who told him that the album chronicles “the average working-class Black man’s story with dignity.” That’s true when the songs reminisce on Mike’s childhood and unpack his family history. On “SLUMMER,” he relives a whirlwind teenage romance that was blindsided by a surprise pregnancy. The girlfriend has an abortion and Mike reflects on paying for the procedure while unpacking his conflicted feelings. For all its awkward wordplay (“They call it adolescence ‘cause we learnin’ adult lessons”), his sincerity carries the song to the finish line. The same can be said for “SOMETHING FOR JUNKIES,” an account of his heart-to-hearts with his crack-addicted aunt, or “MOTHERLESS,” in which Mike works through the grief he feels after losing his mother and grandmother. Pain and pride course through every word as he considers his place in a complicated lineage: “Is this a blessing or a curse, or just some other shit?” he asks on the latter, exasperated. “No matter what, I’m numb as fuck ‘cause I’m still motherless.”

On a technical level, at least, Mike’s raps are seismic. That deep baritone and Atlanta drawl has long rendered his voice one of the most distinct in hip-hop; it’s inspired by the enveloping rumbles of Ice Cube and Erick Sermon as much as it is by Bun B or Big Boi. But what really makes it hit is its malleability. On “SCIENTISTS & ENGINEERS,” a breathtaking Dungeon Family reunion with Future and André 3000, he catches a blistering flow that bubbles and snaps without ever boiling over. With his booming voice, he praises the virtues of Gucci and the work of pan-Africanist scholar John Henrik Clark on opener “DOWN BY LAW,” while “SHED TEARS” and “MOTHERLESS” keep its fullness, but scale down the fire and brimstone for an understated intimacy. He’s hungry and ready to experiment, invigorated by his first batch of (mostly) non-El-P beats in years.

The producers he’s assembled here, which include Tennessee legend DJ Paul, Atlanta mainstay Honorable C.N.O.T.E., and executive producer No I.D., give Michael a lush, stately feel—a stark difference from the madcap sampledelia of Run the Jewels. Choirs, organs, and church bells drive home the pious theme and blend well with booming 808s, cascading synths, and Southern-fried bass licks. The trunk-rattling grooves split the difference between the classic and contemporary South, and it’s refreshing to hear Mike back in his musical comfort zone. “TWO DAYS,” with its wailing guitar sirens and fiery bass fretting, feels like a juiced-up version of Goodie Mob’s “Sesame Street.”

Sadly, that comfort begets some fuckshit. Older solo tracks, like “Don’t Die,” “American Dream,” and “That’s Life,” worked exceptionally well because they spoke with empathy and offered level-headed criticisms of the establishment as much as they fleshed out Mike’s story. Michael still has love for the people, but now it clashes with bars flexing about being a landlord, or homophobic (and dated) Brokeback Mountain jokes. For the first time, he’s punching down, and this bitter disposition gives the album a sanctimonious feel, one that’s usually reserved for his prickliest interviews. When he says “My brother’s in the fire and to save him’s my desire” on closing track “HIGH AND HOLY,” it’s unclear how he decides who’s worth saving. It’s unfortunate to see him trudge further down this path, because at its best, Michael is a funky refresh that often finds clarity in its own backyard.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.