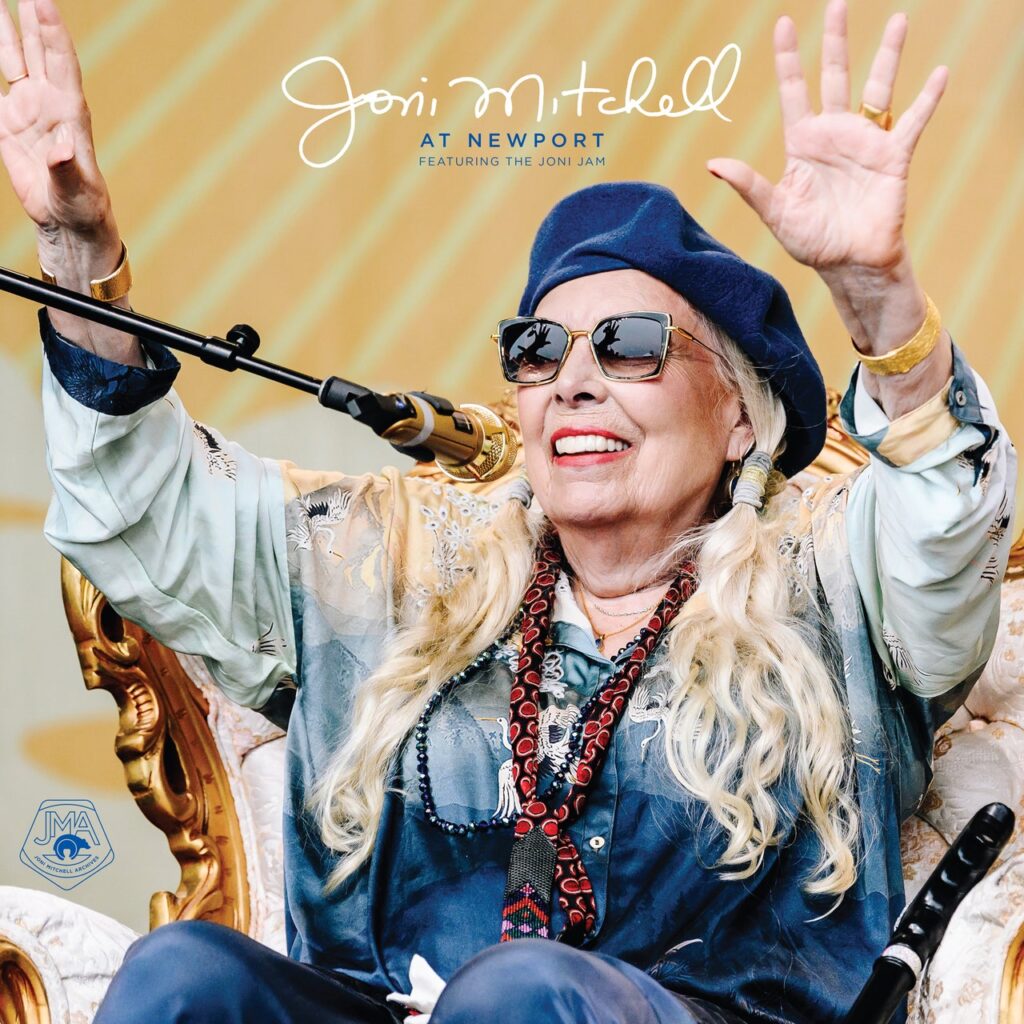

Joni Mitchell’s unannounced set at the Newport Folk Festival late last July was pure social media manna. Just minutes after the most sophisticated singer-songwriter ever associated with “folk-rock” returned to the stage for her first full show in nearly a quarter-century, shaky videos and sunlit photos flooded sleepy Sunday timelines. There was Mitchell, 78, on a stage again, bejeweled and beaming, as if laughing at life’s absurd odds. It felt impossible not to consume every clip, the sacrament of some new miracle.

After surviving childhood polio, devastating post-polio syndrome in the ’90s, and a 2015 brain aneurysm, Mitchell had learned to sing and play some guitar again through a series of loose living-room hootenannies in her Southern California home. Her younger friends dubbed them “Joni Jams.” And now, with a dozen or so of those apostles, she had brought that party to a blazing but joyous Sunday afternoon in seaside Rhode Island. Her appearance was our world’s truly rarest commodity—a complete surprise, thrilling and affirming because it so long seemed impossible.

For all that day’s rapture and wonder, Mitchell’s unexpected appearance never really seemed the setting for a proper live album. (And she has made two, both staggering.) Consider how high passions were onstage, after all, with the acolytes—Brandi Carlile, Blake Mills, Lucius, Allison Russell, Marcus Mumford, and so on—there to assist in Mitchell’s resurrection as her sprawling, spirited band. On most of the songs, the kids took the lead, Mitchell supplying backup for her own songs; on occasion, she took charge, while they offered awestruck accompaniment. You can hear, appreciate, and even admire their ecstasy during At Newport, the hour-long edit of Mitchell’s day in the sun. It’s audible in the onstage squeals after she sings the second half of “A Case of You” or when Dawes’ Taylor Goldsmith stammers “That’s my hero right there” like some smitten schoolboy after he leads “Amelia.”

Such unrestrained fervor, though, makes for an album so frustrating that it actually complicates that memory’s innocent delight. Mitchell’s voice is gorgeous and rich throughout, a piece of high-pile cotton velvet warmed in the daylight. She renders “Both Sides Now” with the wisdom of survival, the “up and down” having still somehow delivered her here. But too often, her patient approach is swallowed by the tide of well-intentioned boosters, associates who make Mitchell feel like little more than an honorary guest at her own party.

Carlile’s role in helping Mitchell return to stage cannot be overstated. During a single decade, she went from a stylistic disciple to the advocate who covered Blue in full to one of the few true believers who held out hope Mitchell might still make music. Mitchell, in turn, used the star-studded and ultimately empowering private Joni Jams that Carlile facilitated as a Jacob’s ladder, unsteadily climbing toward an updated version of her singular voice. “Just watch… Joni’s back,” Mills remembered Carlile telling him after Mitchell sang several songs during a Joni Jam in September 2021. “[Brandi] recognized that moment,” Mills later said in a Mojo interview, “and she could see the future.”

But onstage in Newport, Carlile—to borrow a coveted Mitchell barb—“made some value judgments in a self-important voice,” having checked any ostensible self-awareness backstage. That much even seemed clear simply from early images of the day, where Carlile matched Mitchell, seating herself on an ostentatious Victorian throne and singing into a gilded microphone. (This happened again this June, at a second public Joni Jam.) It is the sort of undeserved equivalence that, even before hearing a note, at least made me wonder how Carlile, who can be a wonderfully boisterous singer, would work with Mitchell, not just around her.

Now on tape, Carlile’s approach to the songs borders on suffocation. At best, she offers serviceable readings of standards, over-singing “Carey” and “Shine” with church-camp gusto and letting Mitchell get in a harmony edgewise. At her worst, though, she distracts from and even drowns out Mitchell, with a maddening insistence on having a say during every track. Her Mariah-lite melisma at the end of “A Case of You,” her unnecessary edict to “Kick ass, Joni Mitchell” before an astounding instrumental of “Just Like a Train,” her incessant humming and whispered phrases during the back half of an otherwise sublime “Both Sides Now”: Carlile is constantly reminding the audience that she’s here, that she’s partially responsible for this. She is such an insistent and pandering presence throughout these songs that, when Mitchell begins Gershwin’s “Summertime” like she’s slinking through some smoky jazz lounge, you half-expect the sidekick to answer “Bradley’s on the microphone with Ras M.G.” (Later, Carlile settles for “Tell ’em what time it is, Joni.”)

This overzealousness pervades the entire performance. The motley troupe’s righteous energy during opener “Big Yellow Taxi” or the choral finale of “The Circle Game” never truly wanes, even during the relatively quiet tunes. Goldsmith, for instance, does an admirable job fronting “Amelia” and “Come in From the Cold,” a perspicacious 1991 single that’s thankfully been salvaged here. His tone is plain and kind, as if offering Mitchell an open invitation to meet near the middle. She accepts it haltingly on “Amelia” but then readily on “Come in From the Cold,” their voices interweaving with an uncertainty tailor-made for the song’s senses of self-discovery and doubt. It is one of At Newport’s few examples of clear vulnerability and risk.

As with Celisse Henderson’s bold interpretation of “Help Me,” even that moment is soon overrun with other voices and instruments, Carlile’s army of Lucius, Mumford, and the like coming down to clutter the clearing. The results subsume the eccentricity, elegance, and innovation of Mitchell’s work, applying a kind of conventional Disney gloss that is the most elementary musical takeaway of the entire Laurel Canyon scene. At Newport is like a selfie snapped from some overwhelming vista, where the faces of the subjects accidentally crowd out the actual sight they’re there to behold. That subsequent Joni Jam this June corrected some of these issues, but here, on tape, they glare and grate.

At Newport does get one thing exactly right, a sometimes-neglected aspect of Mitchell’s career: her humor or, more exactly, her laughter. Even as she has mapped the darkest recesses of our hearts, Mitchell wrote with wit so incisive it was frequently overlooked or even ignored by those who saw her as only lachrymose. But on stage, she’s always been engaged and disarming, constantly ready with a howl or a bon mot. Just listen to the way she cracks during Miles of Aisles when a fan yells “Joni, you have more class than Mick Jagger, Richard Nixon, or Gomer Pyle combined.” Without a word, she obviates every aloof image.

Her laughter is the first thing you hear after the chords of “Big Yellow Taxi” are strummed, the last sound of “Summertime,” and the ellipsis she lets hang following “The Circle Game,” one of the sharpest songs about aging and the perfect exit here. That deep, assuring laugh feels like a better testament to her continued vitality than the album itself. “So fun,” she says when it’s all over. It is one of the very few bits of At Newport that gets better the more times you hear it, the more times you try to relive this surprise.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.