John Coltrane began the decade in which he became immortal in typically audacious style. He quit the biggest jazz band in the world, led by Miles Davis, at arguably the peak of their fame. His early-’60s classics Giant Steps and “Live” at the Village Vanguard planted seeds for free and spiritual jazz, which flowered into teeming subgenres. Before he lost his fight with liver cancer at age 40, Coltrane released definitive albums in both modes, but they were hardly end points for an artist who often seemed to embody flux itself. He went from playing changes to reinventing them. His constant transformations illustrated a quintessential ’60s metaphor: Coltrane’s music rolled along too hard and fast to gather any moss.

In 1961, it picked up speed. A year before his vaunted classic quartet took shape, Coltrane assembled a band and then replaced individual members—not because their contributions were lacking, but because each iteration told him what to do next. Accompanied by pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassist Steve Davis, he released a profound take on Richard Rodgers’ “My Favorite Things” that got so much airplay it revitalized the soprano saxophone. Recording with a new label, Impulse!, Coltrane switched bass duties to 23-year-old Reggie Workman and backed his combo with a slew of auxiliary musicians. The result was the risky, perennially underrated Africa/Brass, which updated the big-band ensembles of yore with transatlantic clave beats and polyrhythms. Anomalous on the surface, such albums offered a blueprint for Coltrane’s future: screeching, unsettled melodies; bottom ends that churned and thrashed; a sprawling palette that mixed in music from India and Africa. Four years had passed since Coltrane quit heroin and resolved to become a “preacher” on his instrument, and now he eschewed the bohemian archness of giants like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie to propound an earnest, devotional relationship with his art. The rest of jazz soon followed suit: A decade later, musicians far and wide explored the spiritual caverns and world-spanning vistas that Coltrane uncovered at the dawn of the ’60s.

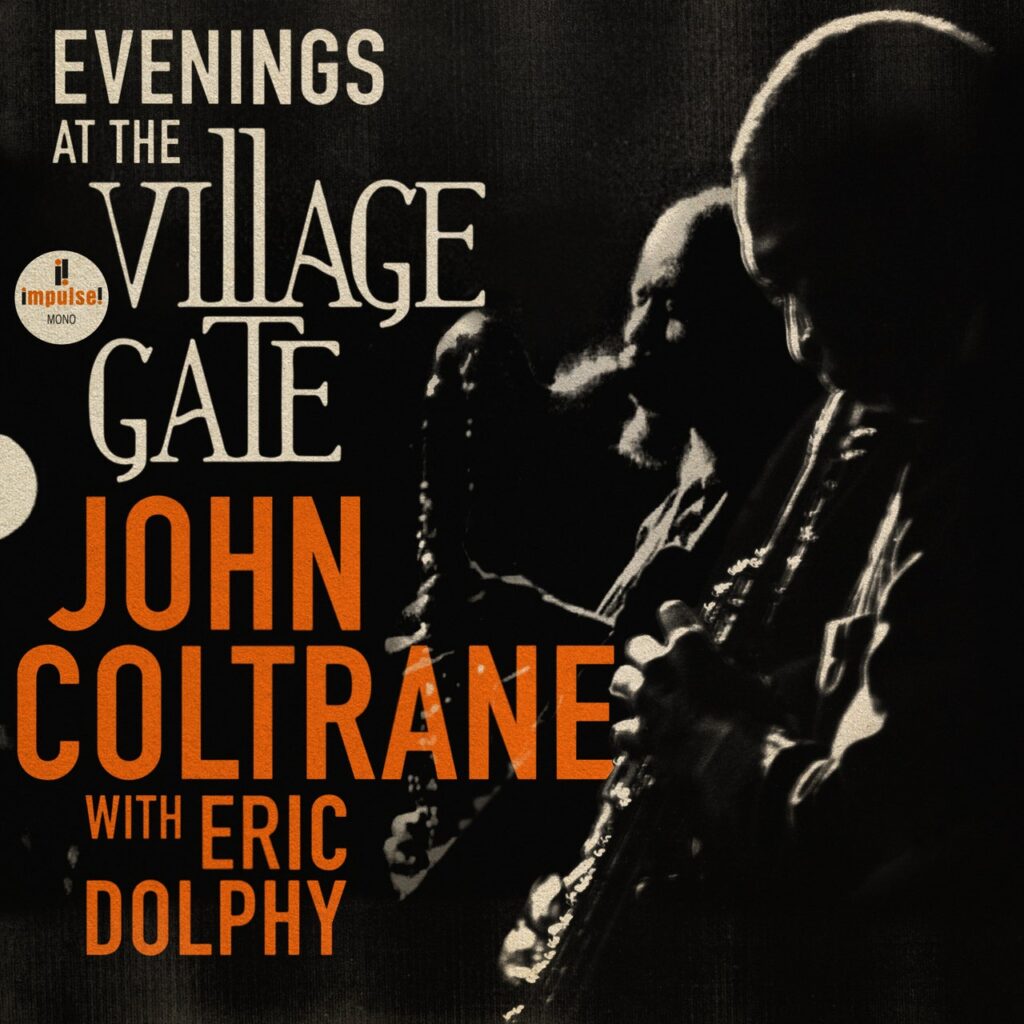

Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy, a new archival release, captures the 34-year-old artist as he comes to grips with his music’s remarkable possibilities. The album is culled from a couple of nights during an August and early September residency at the Village Gate, a since-shuttered Greenwich Village venue. Containing just five songs in 80 minutes, the set is nonetheless comprehensive. Coltrane plays a hit (“My Favorite Things”), a standard from before his era (1936’s “When Lights Are Low”), a song that he would not put out on record for several years (“Impressions”), and a couple of recordings that the world was about to hear in studio form (“Greensleeves” and “Africa”). The LP is a freeze-frame of jazz as it escapes the present and absconds to the future.

It also illuminates Coltrane’s work with a tragically short-lived fellow traveler, Eric Dolphy. Unlike Coltrane, who was keen on modality, Dolphy experimented without abandoning tonal concerns. He was a crackerjack soloist who could make any stray bleat from his mouthpiece sound soulful. The quartet welcomed him in the spring of ’61 as a featured sideman, and he left fingerprints on much of what Coltrane accomplished for the rest of the year. The multi-reedist orchestrated large sections of Africa/Brass in May and June, and his solos took over the bandstand while he gigged with the band that summer and fall. Just as Coltrane did for Miles Davis during their final shows together, Dolphy widened Coltrane’s canvas. The two had been friends for years. Coltrane even carried a photo of Dolphy with him after he died, at 36, in 1964, from a diabetic coma, hanging it on the walls of hotel rooms while he traveled. But the beauty of their interplay was tightly wound in the tension of two self-directed men with irrepressible appetites for innovation. Coltrane understood that he had to carve out space for Dolphy’s individuality within his band. He purportedly sat offstage during Dolphy’s solos at the Village Gate, magnanimously handing the reins to an artist who would express himself regardless.

Critics tout Coltrane’s soprano saxophone as the key that unlocked the door to spiritual jazz, yet Dolphy’s similarly unconventional instrumentation greased the hinges. The version of “My Favorite Things” on Evenings at the Village Gate begins with a prelude from Dolphy’s flute, airy and ascendant, before the main horn line offers solid footing. On the next track, “When Lights Are Low,” Dolphy’s bass clarinet simmers below Coltrane’s tea-kettle sax tones. Together, they liberate the cut from its worn page in the jazz fakebook.

Coltrane’s road to the avant-garde was built from his ability to compose, arrange, and imagine new roles for diverse instruments on his bandstands. He divided rhythm duties, writing static harmonies that pulsed through his piano lines, permitting more movement from drummers and bassists. On “Greensleeves,” Tyner’s hypnotic chords riff on the motif from “My Favorite Things.” Meanwhile, Jones tumbles out of a waltz and through a seemingly endless fill on the toms and cymbals. Some of the Village Gate dates featured a second bassist, Art Davis (no relation to Steve), who provided drones and allowed Workman to roam without restraints.

Album closer “Africa” emerged from one of those nights. It’s the only live rendition of the Africa/Brass centerpiece known to exist on tape. The song begins with applause, as the band teases a fleeting figure from a George Gershwin tune that Coltrane reinvented, “Summertime.” Davis plunks away regularly, enabling Tyner to sprint up and down the keys and Workman to navigate a searching bass solo. Africa/Brass was Coltrane’s most unusual album in the busy year of 1961, and it landed on shelves near the end of his run at the downtown venue. The inclusion from his latest, weirdest disc coaxes the audience to polite applause and probably some puzzlement, too.

Confusion was a frequent reality at the Village Gate, a hall that prided itself on its sometimes disarming variety. Comedy acts appeared after avant-garde jazz musicians. Experimental luminaries performed on the same stage as popular singers. During various appearances at the Gate, Coltrane faced skeptical audiences who had come to see folk singer Odetta, blues legend Lightnin’ Hopkins, and 19-year-old Aretha Franklin. The shows included on Evenings at the Village Gate were shot by photojournalist Herb Snitzer, who claimed that the room was half empty; he imagined Coltrane had made five or “maybe ten bucks” from the concert. The dog days of summer were in full swelter, and the venue had to lure listeners out of their homes and onto the sticky Village streets for dinner (bad service, but apparently tasty food!) and a show. Yet it’s hard to imagine that Coltrane and co. cared much about their audience. The sound from the stage is an elemental force blasting through the soporific climes, shaking the empty seats.

Across the hall, one spectator made a spontaneous decision. Twenty-four-year-old engineer and Village scenester Rich Alderson wanted to test the club’s sound system and also an old RCA 77-A ribbon microphone he had modified. Coltrane and club owner Art D’Lugoff never meant to cut a record, but Alderson captured a couple of evenings and then forgot about them. He soon moved on from the Village Gate—eventually, Alderson built the sound system for Bob Dylan’s mid-’60s tours—and the recordings were lost until a Dylan scholar discovered them by accident while doing research at the New York Public Library in 2017. Another piece in the puzzle of John Coltrane arrived, as it should, by improvisation and chance.

Still, the rudimentary production will frustrate fans who seek sonic perfection from mid-century pioneers. Tyner’s piano is muffled enough on “My Favorite Things” that his parts can sound like ghostly percussion unless you focus on them. Basslines are sometimes difficult to unearth from the tumult, with the notable exception of “Africa”—ditto Dolphy’s more delicate trills. Scores of Coltrane heads weaned themselves on the impressive fidelity of “Live” at the Village Vanguard and 1964’s Live at Birdland, both of which were captured with extreme stereo know-how by Rudy Van Gelder. Fans expecting this treatment may be displeased, but their reactions befit the artist—Coltrane never liked meeting expectations.

His Village Gate set offers us something beyond pristine audio: extraordinary energy. The parts we cannot clearly perceive murmur away, offering fullness to the music anyway. Improved sound quality wouldn’t make the listening experience more authentic—but it could make it fussy, more in keeping with sterile 21st-century airpods than an acoustically challenged Bleecker Street basement in the early ’60s. (This basement remained a venue, Le Poussin Rouge, after the Gate closed 30 years ago; the ground floor, naturally, has become a CVS.) Alderson placed his single mic near Elvin Jones, whose elastic drumming feels like a marvelous solo act. He flails against orthodoxy, rattles the bars of swing time and jeers at the expectations of consistency that percussionists have to shoulder. Ostensibly a timekeeper, Jones was the wildest member of Coltrane’s ’61 quartet, and perhaps as a result he was the last player of this era that Coltrane would replace.

At the end of the year, Workman left— his father was sick and Coltrane had a new trajectory in mind. Dolphy departed soon after, eventually joining Charles Mingus’ band for the second time, where his deft reedwork could take center stage. The quartet reshuffled as Coltrane surged forward. These Village Gate performances, though, continued to reverberate in his own music and in music at large. There were precedents for composers using two bassists, but arguably no one before Coltrane had saddled one bassist with roving lead parts and another with a stationary, raga-inflected drone. Coltrane battle-tested this dynamic at the Gate, and then developed it over the years. His experimentation signaled something both impractical and studied, a breakdown of big-band largesse into the endless permutations that opened to jazz musicians as ’50s conventions fractured into parallel universes of sound. Within a month of the Gate performances, Ornette Coleman released Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, which used two bassists. In 1966, Cecil Taylor doubled up bassists on his uncompromising Unit Structures. By 1970, Coltrane’s former boss Miles Davis was using two bassists on a game-changing release in a far different vein, Bitches Brew.

The poet and jazz critic Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones), in his gorgeous liner notes to Live at Birdland, called McCoy Tyner “the polished formalist of the group” and claimed that he played more cautiously than his bandmates. Baraka’s comment became writing on the wall—in 1965, Coltrane replaced Tyner with his wife, Alice Coltrane. But the saxophonist was merely trying out something new, not deriding something old. Perhaps because he died tragically young, it’s easy to imagine that Coltrane had a destination in mind with his music, some heavenly realm formed of sacred geometries and unceasing magic-hour light, where an even more classic quartet plays nonstop with Rudy Van Gelder perched behind the sound boards. In reality, had Coltrane lived to ripe old age, he would have continued to try out different styles, bands, influences and ideas, no doubt jamming with past collaborators along the way. Squabbles about sound quality, and comparisons between various iterations of his quartet, are never convincing: John Coltrane cared about change, not perfection.

He played “My Favorite Things” during his last recorded concert, in 1967, at the Olatunji Center for African Culture in Harlem. The version bears no similarity to the original except for a several-second phrase during a breathless solo. These familiar notes are surprising after an onslaught of free jazz, masterminded by a terminally ill genius who had passed through all sorts of flames in order to become the most transformative, intense and grating saxophonist in the world. Then again, Coltrane once said that he considered “My Favorite Things” to be the best recording he ever made. He liked the composition because he could play it fast or slow, because it “renews itself according to the impulse you give it,” because it was a good place to start.

On Evenings at the Village Gate, Coltrane treats his hit as raw material. He adapts it for another soloist, and rebuilds it into other tracks, one of which he dedicated to Africa. The experience recalls a quote that, like his music, has been referenced too often but retains its grandeur all the same: “I want to start in the middle of a sentence and then go both directions at once.” Coltrane reaches at once into the future and the place where music began. He touches the primeval and follows along with the changes.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.