Jason Lytle is an unlikely spokesman for our electronic companions. As an amateur skateboarder growing up in the Northern California city of Modesto, the Grandaddy frontman aspired to a career working in the elements: a fireman, or perhaps a park ranger. Instead, a skateboarding injury forced him inside, where he befriended circuits and sequencers and rediscovered an early love for the guitar. Joined by bassist Kevin Garcia and percussionist Aaron Burtch, Lytle released a series of early Grandaddy EPs before the band put out their debut, 1997’s lovably unrefined Under the Western Freeway. Their breakout second album, 2000’s The Sophtware Slump, drew comparisons to the sci-fi surveillance state of Radiohead’s OK Computer. Combining the disillusionment of nearby Stockton, California slackers Pavement with kaleidoscopic synths and surprisingly poignant lyrics about broken vacuums, Grandaddy brokered an uneasy peace between the flagging post-grunge landscape of American indie rock and the impending digital dominance of electronica.

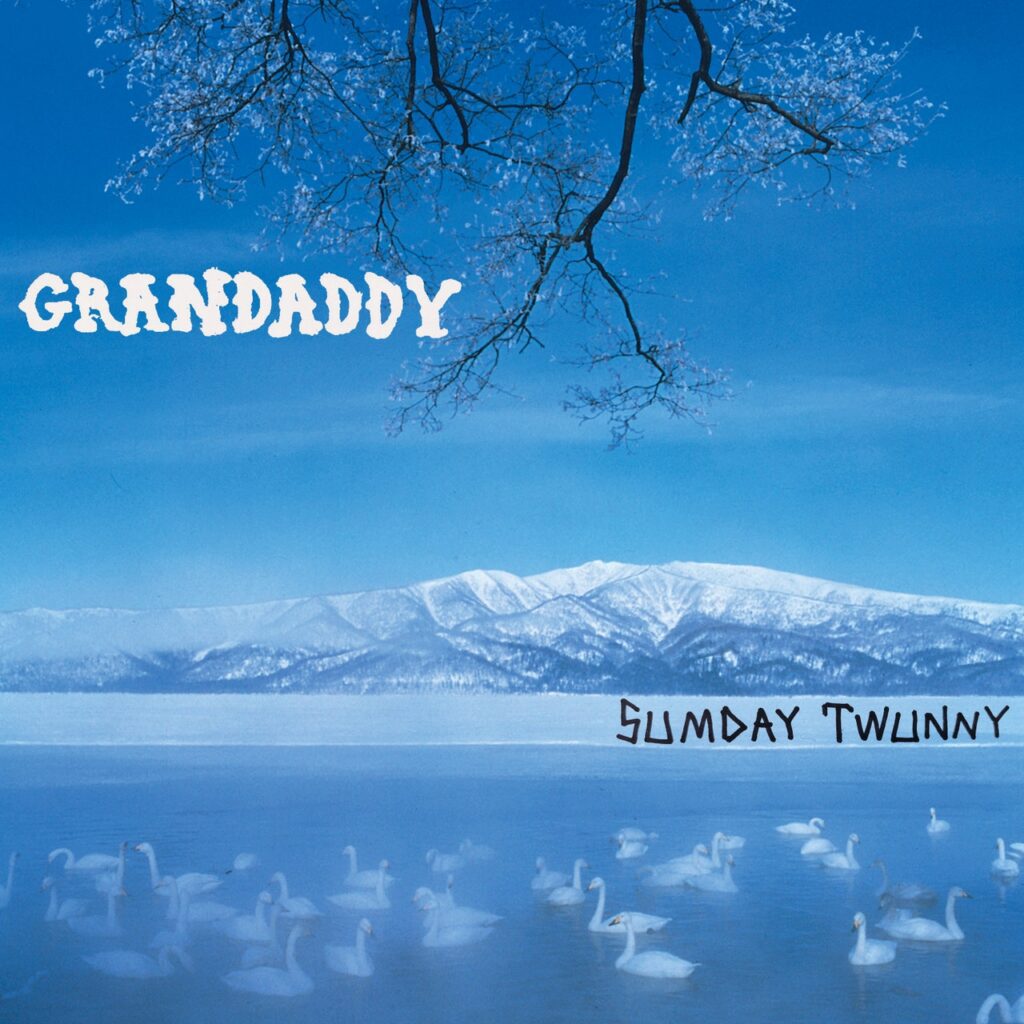

But after years of endless touring, Lytle and his bandmates were waning. It wasn’t just the physical trials of life on the road—they were tired of singing about dead humanoids and abandoned appliances night after night. For their third album, 2003’s Sumday, they went into Lytle’s home studio with a few explicit goals. “It had to be more optimistic and it had to be more concise,” guitarist Jim Fairchild recalled. The bar was low—their last album opened with a nine-minute epic about an alienated astronaut—but while song lengths averaged out at a much more reasonable four minutes, Lytle still revealed new anxieties about the future, even as he tried to unplug. For the album’s 20th anniversary, Grandaddy have released a box set that includes remastered recordings, four-track demos, and a collection of unreleased songs from contemporaneous studio sessions. Lytle’s ambivalent premonitions of our digital age, underscored by a growing listlessness in the face of capitalism’s death drive, sound both quaint and prescient in our hyper-mediated present.

Even at the time, Sumday stood apart from its predecessors. “Now It’s On” roars with a confidence and cautious hope that breaks from the existential woes of The Sophtware Slump and its wayward space cadets. “Once you’re outside you won’t want to hide anymore,” Lytle sings over a palm muted guitar, his rosy outlook finally catching up to his perpetually sanguine vocals. And though there are layers of pixelated texture on songs like “O.K. With My Decay,” analog instruments dominate the record’s sound, apt for an album about returning to nature. “Saddest Vacant Lot in All the World,” brimming with Grandaddy’s characteristic layer of ambient noise, demonstrates that Lytle can build worlds just as bleak as his digital dystopias from only a piano. The cassette demos, which for the most part keep the same shape and feeling as their fully realized versions, similarly showcase what his music might have sounded like if he fully explored this stripped-down setting: “The Go in the Go-for-It” is transformed from a buzzy, hunched over rock song to a plaintive ballad.

The reissue also includes a dozen songs from the cutting room floor, now released as their own album under the name Excess Baggage. Grandaddy obsessives, who have dutifully cataloged the band’s myriad unreleased demos and live performances, will recognize most of the material: “The Town Where I’m Livin Now” existed as a live cut for years before Lytle released an official version under his own name. Others like “Derek Spears” only existed in shaky YouTube videos. The tale of an itinerant eccentric down on his luck, it’s a peek into the lives Lytle observed in Modesto— “He says he made 90K a year before he hurt his back”—but he shelved the song because “the only people who really get this song are people who live in the Central Valley.” Other songs, like “Running Cable at Shiva’s,” sound right at home next to Sumday’s “Stray Dog and the Chocolate Shake,” with chirping keyboard synths and lyrics about the “slightly living dead.” The close-miked “Dearest Descrambler,” a song so thin it threatens to vaporize at any moment, crash lands with an evergreen economic anxiety: “Is it too late for me to master a trade?”

Compared to their contemporaries—Mercury Rev, Sparklehorse, the Flaming Lips—Grandaddy excelled at demystifying the terrifying unknown, even if that familiarity still bred contempt. Rather than foretelling a future of epic battles against robot armies or pianos crumbling into the sea, their songs described people in a world much like ours, existentially vacant and starving for meaning. Lytle’s androids weren’t paranoid, they were idle; his robots weren’t evil-natured, but lonely. He turned his lens at the inner lives of machines, finding their rusting husks as tragic as a washed up drunk at last call: limousines without a celebrity to chauffeur, factory robots toiling in the dark, emails crying out in our inboxes for the gaze of a weary human eye. Perhaps it was this ability to connect fears of the future with the quotidian angst of our daily lives that made David Bowie, progenitor of the lonely space age explorer, such a huge fan in his later years.

Where Grandaddy’s previous albums focused on our tactile, external interactions with technology, Sumday hinted at the ways it was beginning to change us from within. “The Group Who Couldn’t Say” follows a team of office workers who win a trip to the great outdoors, only to find themselves too stunned by nature’s beauty to speak. Even lyrics that should sound dated in our post-iPhone parlance—“Her drag-and-click had never yielded anything as perfect as a dragonfly”—are resonant in their sense of wonder. It speaks to the same thirst for escape that sends startup lackeys to Burning Man every year, but cloaked in hazy synths and soft “doo doo doots,” it remains a picturesque vignette rather than a superficial quest for salvation. On Sumday, Lytle presented a world where we become so accustomed to technology that its absence is felt more strongly than its omnipresence.

While Sumday presented an idyllic exit for Grandaddy, it also forecasted the beginning of the end. Touring and recording had taken its toll, and Lytle harbored a desire to escape the constant churn of album cycles. “I feel so far away from home,” he sang mournfully on “El Caminos in the West.” In interviews, he spoke about the band’s future with palpable exhaustion: “If I don’t end up dying in the process, I might benefit from another life after music. I won’t try to extend the dream until it becomes pathetic.” As he put it on “The Go in the Go-For-It,” the industry “tried to wreck” his head, and he wanted out. Sumday, then, is his journey to rediscover the world outside of his studio, the would-be park ranger moving through life like “wind blowing through the leaves.”

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.