Saleh and Daoud Al-Kuwaity were giants in Iraq. The brothers played violin and oud in the courts of kings and composed new standards for the greatest singers of the Arab world, reshaping Iraqi classical music for the 20th century. But when they emigrated to Israel in the early 1950s, their stature and earning power plummeted; they sank from concert halls to private parties. “My father sold eggs,” Daoud’s daughter remembered in the documentary Iraq N’ Roll. After all, they were Arabs. Still, they retained their fame in Iraq—for a time, until Saddam Hussein had their works redesignated as anonymous folk songs. After all, they were Jews.

Born in Kuwait, with Iranian and Iraqi ancestry, Saleh and Daoud were part of the Middle Eastern and North African Jewish diaspora that came to be called Mizrahi after the State of Israel was formed. As the great Iraqi Jewish musician Yair Dalal put it in the documentary, “It was an identity with a question mark,” and it did not align with the cultural establishment’s European biases. “Their entire journey was blotted out” in both their ancestral and chosen homelands, Iraq N’ Roll director Gili Gaon told Haaretz. Because of this, Saleh and Daoud forbade their children to pursue music. “But it returned in the grandchildren,” Dalal said, moved to tears by the playing and singing of a younger musician named Dudu Tassa.

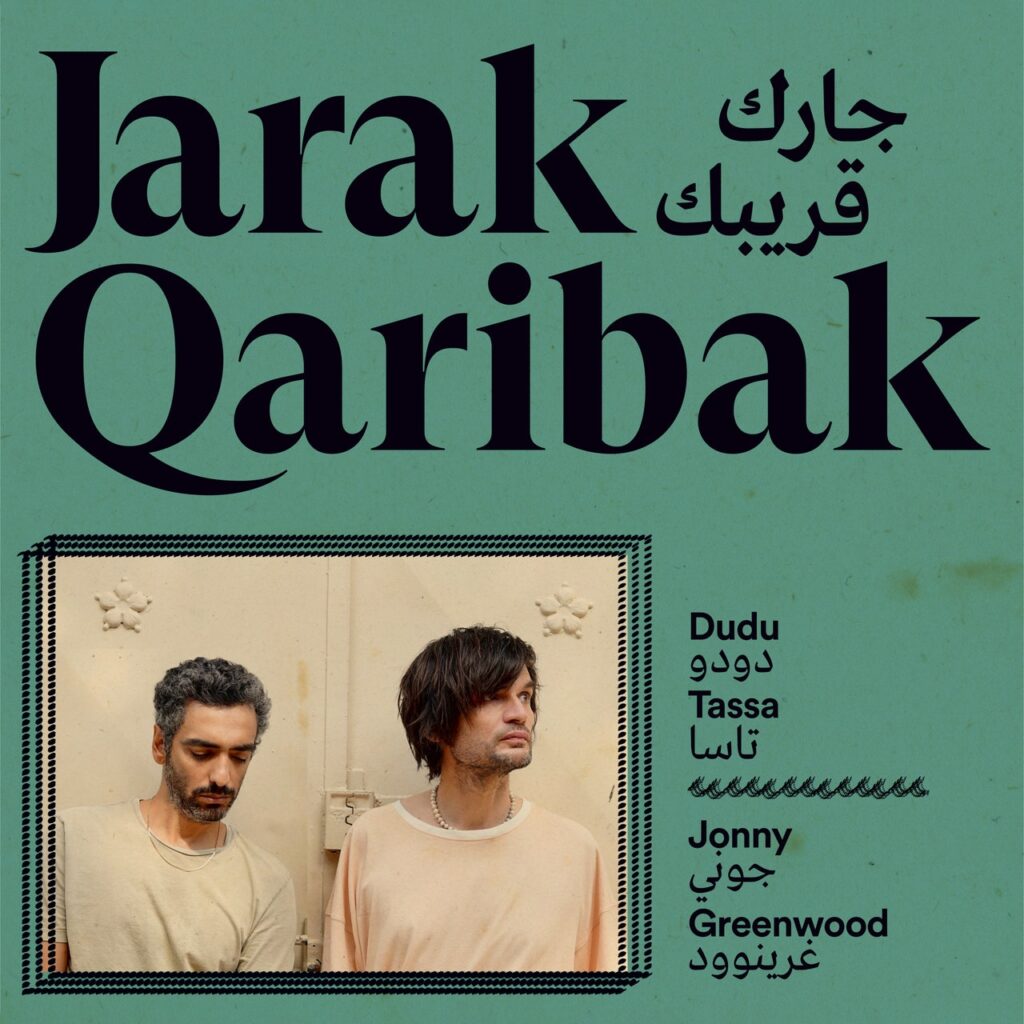

Tassa is the grandson of Daoud and the grand-nephew of Saleh. His music, sung in Hebrew and Arabic, is big in Israel but less known in the States, and to a foreign newcomer, he seems like a slightly scruffier Chris Martin: a polished, generous rock-and-ballad performer of evident popular appeal. Since 2011, Tassa has been reviving Saleh and Daoud’s music and prestige with his rock band the Kuwaitis, which Radiohead once took on a U.S. tour. Their guitarist, England’s Jonny Greenwood—who is married to Israeli artist Sharona Katan—also played on the Tassa-penned 2009 song “Eize Yom.” Thus the conditions were set for Jarak Qaribak, an altogether extraordinary album that seems to create new pieces for the geopolitical puzzle of its backstory, as if doing so might be the solution to eventually completing it.

The title means something like “Your neighbor is your friend,” and the singers come from all over the Middle East. In a quietly ingenious touch for a study of imbricate identity, all of them sing songs from countries they aren’t from. The album consists almost entirely of Arabic love songs, an ancient, refined tradition admired the world over, and one that contains far more than eloquent longing. Take the spark and highlight of the project, a Lebanese song called “Taq ou-Dub,” rendered as a palpitating dance track where sweet flutes reel with tangy plucks. Palestinian singer Nour Freteikh softly bends the title’s three percussive syllables into an adhesive hook. It’s even zestier if you know it means “take a hike,” and the whole thing is basically a Swiftian excoriation of an ex.

While this song was recorded live, most of the vocalists recorded in their home countries. Greenwood and Tassa traveled between Oxford and Tel Aviv to make the music with players of brass, strings, keyboards, and Middle Eastern instruments. Ariel Qassis plays the silky Arabian zither called the qanun, while Mustafa Amal plays the rebab, a spike lute found throughout Islamic culture. There are bamboo pipes and, of course, the intricate intervals and supple slides of the fretless oud. Tassa and Greenwood blend in standard rock kit; the former sings on an electro-cinematic version of the Moroccan song “Lhla Yzid Ikhtar,” while the latter has described the production vision as Kraftwerk in 1970s Cairo. The use of drum machines instead of computers helps to give the piecemeal recording its warm, live feeling.

It would be miserly to call these songs simple covers: The range of interpretation between the microtonal scales and interwound melodies of Eastern music and the harmonizing octaves of the West is too wide for that. Yet the album’s arrangement closes the distance with skill and sensitivity, flowing easily from electronic music to torch songs to classical bricolage. But the difficulty of this musical bridge-building pales next to what it took for this project to exist at all. Tassa has hinted at what one would imagine to be considerable bureaucratic and diplomatic efforts behind getting some of these artists to work with him or one another. Thus the record is organically, even experimentally, political—not narrowly or expressly.

On the other hand, it never would have come about without Greenwood and Tassa choosing to use their clout to do something hard and rewarding. There’s no other circumstance in which the Egyptian singer Ahmed Doma would give a suave account of the Algerian Ahmed Wahby’s “Djit Nishrab,” and Iraq’s Karrar Alsaadi would travel to Tel Aviv to commandingly sing a Yemeni song, and Dubai’s Safae Essafi would fashion a sleeper hit from an Israeli song, “Ahibak,” with its ’60s spy-jazz groove, like fingers running over a beaded curtain. And there’s a tune by Tassa’s great-uncle Saleh, at last restored to his proper place in this story, in a haunting yet poppy rendition by two Tunisian singers. Jarak Qaribak is a rich, fascinating case of music both carrying history and shaping the future, redrawing the limits of the possible in specific, limited, yet meaningful ways.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.