Something secret is happening in JR Seaton’s work as Call Super. Over the last decade, they have developed a private language for their largely instrumental electronic music, which skirts the edges of the dancefloor like a small woodland creature slinking through the underbrush. Pay attention to the track titles, and weird patterns and semi-rhymes emerge—apparent series like “Okko Ink,” “Ekko Ink,” and “Ekkles,” or Arpo and “Arpo Sunk”; vowel-heavy names like Suzi Ecto, “Sulu Sekou,” “Fluenka Mitsu”; the aliases Elmo Crumb and Ondo Fudd. These mysterious, staccato words and phrases, occasionally nodding playfully to Harpo Marx or Elmer Fudd, suggest a code that might unlock the secrets of the UK musician’s invented universe, if only we could crack it.

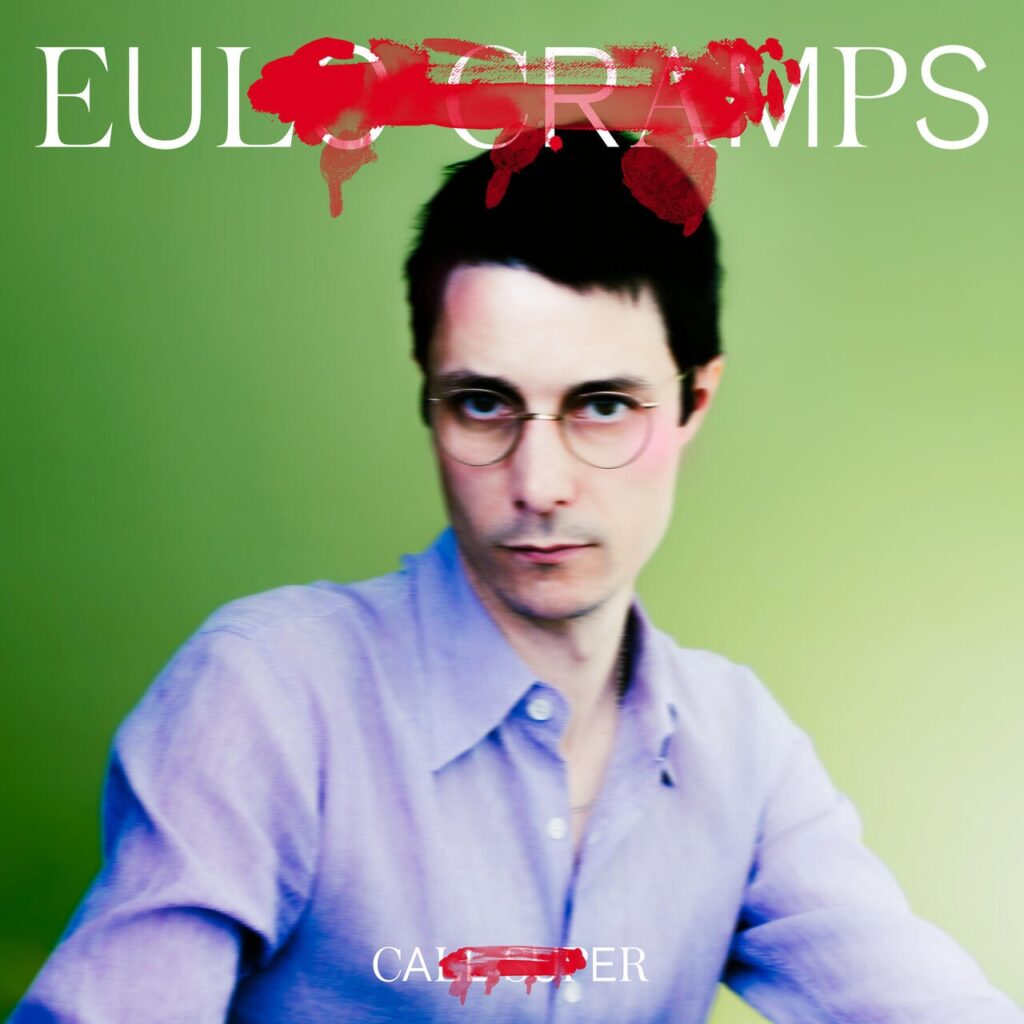

On Call Super’s fourth album, Eulo Cramps—there’s another one of those cryptic titles—this trail of breadcrumbs leads not out of the woods but deeper into it. Seaton started out in the early 2010s making stern, barnstorming club tracks, and they’ve never completely abandoned their dancefloor tendencies—just see the lush, quick-stepping “Swallow Me,” from last year, or the sparkling floor-fillers of 2021’s Cherry Drops I and II. But Call Super’s three previous albums have frequently strayed far from club convention, swapping four-on-the-floor beats and crowd-moving riffs for serpentine clarinet melodies and crinkly textures of tin foil and bubble wrap. Those motifs, indebted to both Jon Hassell’s ambient jazz and the electric-typewriter rhythms of early IDM, have become signature elements of Call Super’s music. On Eulo Cramps, they render their most holistic and beguiling vision yet.

The new album is part of a broader multimedia project, Tell Me I Didn’t Choose This, that will combine text, painting, and music. But even experienced in isolation, Eulo Cramps feels like a culmination of ideas that have been bubbling in Call Super’s work for years. It’s shot through with acoustic or acoustic-sounding instruments: piano, congas, drums, bells, and harp strings. Melancholy clarinet melodies—played by Seaton’s father, then multi-tracked into eerie harmonic clouds, or twisted and pitch-shifted into surreal, synthetic ribbons—form the tonal center of many tracks. Sounds jostle together, collide, and sometimes fuse, endowed with an unusually tactile heft. In some moments, it feels as if Seaton has daubed on keys with a sponge or putty knife, yielding thick, gloopy streaks; the high end bristles with metallic shards and wooden splinters. It’s the most vivid sound design of the producer’s career.

Three tracks toward the beginning tap into Call Super’s powerful rhythmic instincts: The rippling “Fly Back Stork” sounds like a forceful response to Ricardo Villalobos’ classic “Fools Garden (Black Conga),” while muscular drum fills propel “Sapling” and “Illumina Spin” along their rolling journeys. But little here sounds like typical dance music, and the deeper the album goes, the more things pull apart at the seams. The harp strings and clarinets of “Glossy Bingo Stain” proceed haltingly over uneven hand drums whose rhythm is difficult to parse. “Coppertone Elegy,” which sounds like the Cure’s Disintegration remade for the experimental techno set, layers scraping textures over glowing pads, acoustic guitar, and indistinct murmurs; there’s no center, just a boundless expansion. Occasionally, the crackle of an audio cable in a socket will interrupt the flow of a track. In the dirgelike “Clam Lute Wig,” it sounds like Seaton is reaching into the murk, rooting around to see what lurks there, and stirring up meditative chaos.

Even the album’s guest vocalists convey a similar sense of fragmentation. In “Sapling,” Canadian singer Eden Samara’s voice is split across the frequency spectrum like light through a prism; every so often, an intelligible phrase (“Your taste concealed”) will surface amid all the dappled accents. Something similar happens to Julia Holter’s high, breathy voice in “Illumina Spin,” vaporizing it into a lustrous mist. Even the spoken words of Berlin’s Elke Wardlaw, which run through the core of “Goldwood,” are processed in a way that suggests pulverization, lending her assonant rhymes an atomized, pointillistic feel.

This fractured aspect goes to the heart of the album’s underlying themes. Seaton has discussed Eulo Cramps in autobiographical terms, hinting at youthful traumas: They have said that “Coppertone Elegy” is about the multiple selves within us, while the closer “Years in the Hospital” engages the memory of a long period of illness. Beyond a stray word here or there, these inspirations may not translate to the listener, but that hardly matters. What’s clear is how carefully Seaton has approached every sound on the record, always avoiding the familiar path in favor of the one that burrows deeper inward, the better to flesh out the contours of their inner psyche. Eulo Cramps is that rarest of albums in dance-adjacent electronic music: a record as personal as it is original.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.