The world has never been noisier. For people who grew up uncertain of being heard—and for people of color, queer people, and, most especially, Black trans folks, who grew up certain of being deliberately misunderstood, even silenced—not all the noise is good. But for more than half a century, Beverly Glenn-Copeland has been offering an alternate tuning.

His first two albums fused personal poetics to avant-jazz-folk; he spent the next 15 years or so split between playing in the house band of a beloved children’s television show and living deep in rural Canada, where his soundtrack was the woods. Meanwhile, the universe was feeding him songs through what he calls the Universal Broadcasting System. He made an album of them, 1986’s spellbinding, DX7-driven Keyboard Fantasies, whose mysteries found receptive ears when Invisible City Editions reissued it some three decades later. His groovy album Primal Prayer, originally released under the artist name Phynix in 2004, was reissued. There was also a reverent documentary, a career-spanning compilation, a live album documenting the astonishing strength of his versatile voice, a remix album proving few could better his originals, a Polaris Prize. His echoes were everywhere, old and ever new.

The Ones Ahead is the first album of new material since all this happened. It’s a remarkably assured statement of purpose. Crafted in collaboration with music director John Herberman, with chart arrangements by Carlie Howell and performances by Howell and other members of Indigo Rising, who back Glenn-Copeland on his rapturous live shows, the album is largely a staging ground for his vision and his voice.

And what a voice. “Harbour (Song for Elizabeth)” makes a warm bed of fretless bass and crisp, resonant piano. He confesses to his wife, “My heart aches/When your tears flow.” His vibrato is a blanket that stretches as he sings, then rumples as he sinks into a lower register: “But then spring breaks/And that’s all I know.” Love, queer love, is a force of nature. “Love Takes All” is darker, bolder. Drums rumble, a guitar slides like rain down trees. “What was grand or small,” he proclaims, as the word grand sounds like it’s stretching his throat into canyons, “love just takes it all.” Doesn’t it just. Doesn’t love just require everything to last.

Here, like Kate Bush in her Aerial days, Glenn-Copeland threads the quotidian and the mystical into knots. They secure him in “Lakeland Angel” as he and the titular siren trade serenades; the couple need each other, and tend to that need as simply as a hand splaying out across a keyboard, forming chords. The ties to Christian mysticism or Narnia LARPing might be a little too tight, for some, on “Prince Caspian’s Dream,” with its washes of cymbals and whistles. But these days, it might be forgiven to slip into dreaming of other worlds while dreaming up better versions of this one. One might, in the middle of a backlash summer in which friends are losing loved ones and enduring violence and wondering just how bad things might get still, experience a loneliness forgiven by Glenn-Copeland’s voice. Or at least I felt I was, while listening.

Elsewhere, Glenn-Copeland builds homes for himself and his loved ones in rhythm. Opener “Africa Calling” brings it home with call-and-response murmurings, lusciously recorded rustling percussion, and some lovely, bittersweet jazz piano toward the end. “Stand Anthem” is a rabble-rouser: A strident march begins, a dignified melody follows, and Glenn-Copeland leads a chorus towards action, articulating modern ills with confrontational earnestness. “People of the Loon” is more surreal, but no less committed to refusing cynicism. When I talked to him in 2020, he told a story of kayaking on a silent lake, and suddenly being surrounded by a circle of dancing birds. This song is itself a circle of mallet instruments, drums, streams of strings. “Come a little bit closer,” he and his group chant, “for each there must be room.” Like the best psychedelic visions, it’s a little silly, a little scary, equal parts pagan poetry and political organizing. (Get your samplers ready.)

The title track waltzes in with a gentle appeal for personal agency and collective responsibility intertwined with an almost biblical prophecy. “’Neath the starfields burnin’/I see the ones, I see the ones ahead/Circlin’ on the river,” he sings. “This world is our combined imagination/Your life, a personal creation.” Listen to other stories, then make up your own. In the astonishing closer, “No Other,” Glenn-Copeland refuses to accept the alienation this lousy world wants for him, for us. “I am a child of this world,” he proclaims. Amid martial drums and in marital bliss, and there’s that damn whistle again, he hears those who came before and he foresees us following his lead. It sounds turbulent and so sincere.

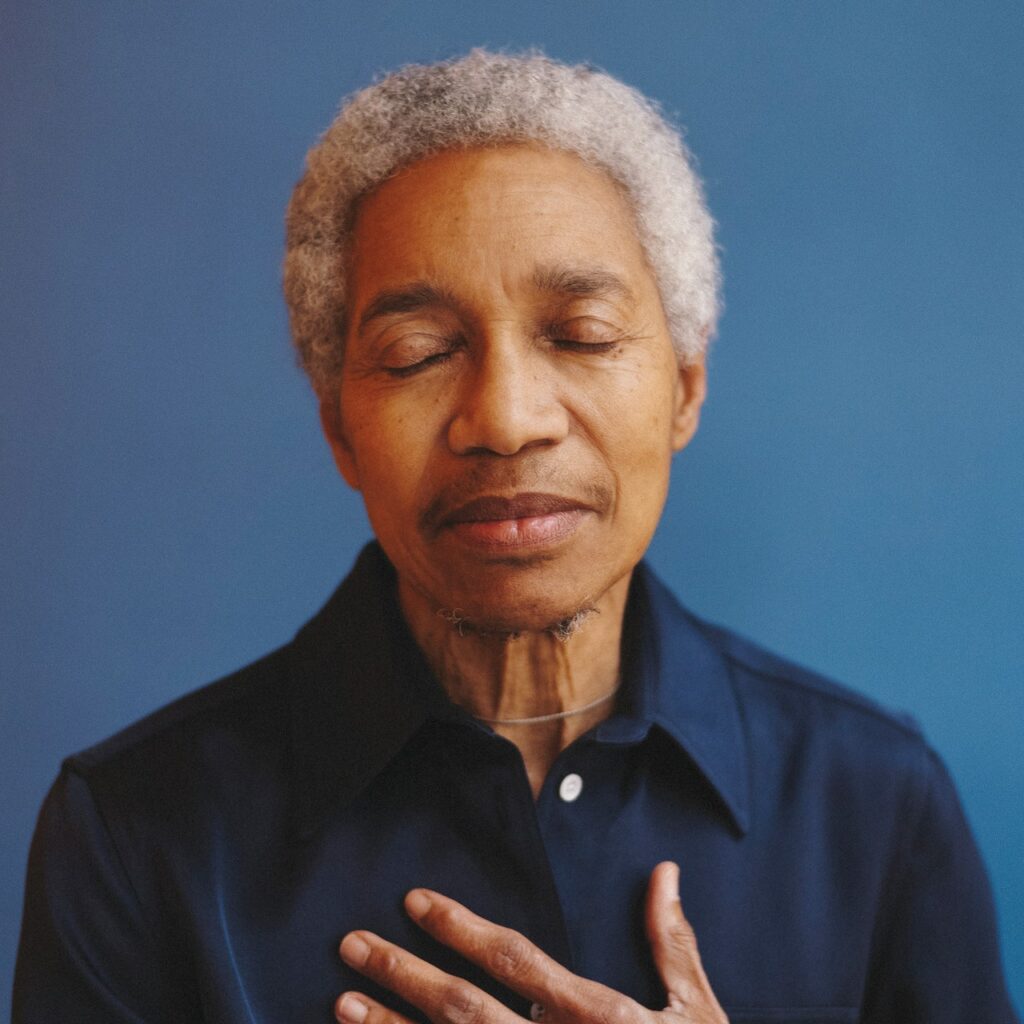

It’s deeply moving to witness Glenn-Copeland survive, to watch the next generations find their freedom in him. When the spotlight found him, it felt, in part, one of those rare moments when a true genius—a Black, Canadian trans man in his seventies who made one of the best electronic records of the 20th Century, who could coo like Billie Holiday and croon like Frank Sinatra and command like Buffy Saint-Marie and run like Beyoncé and probably even, if he wanted to, rip your soul in half like Diamanda Galás but instead chose to heal it like nobody else—was finally getting his due. Beverly Glenn-Copeland is an unprecedented talent who reminds us that each of us is rare. There’s so much more to hear, so many more of us to listen to. The Universal Broadcasting System is still switched on.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.