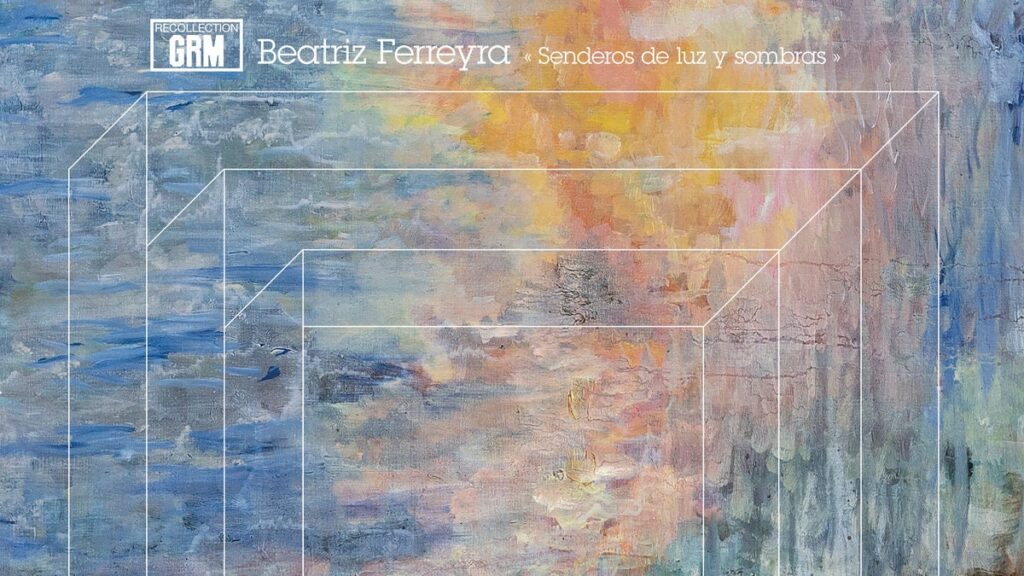

Part and parcel of Beatriz Ferreyra’s compositional practice is the act of surrendering to music. “I do not think of anything,” she’s explained; “the sounds with their colors, their shapes, and their dynamics take me by the hand and take me where they want.” The pioneering Argentine experimentalist has decades of work that are sprawling in this way, grandiose in both ambition and impact because of sound’s unpredictable, commandeering nature. Her 1972 composition Siesta Blanca transmogrifies Astor Piazzolla tangos into elemental sensations of cold and heat. Dans un point infini, from decades later, is a longform epic built on screeching, manipulated strings. Her latest album features what is perhaps her loftiest work: a 30-minute composition written between 2016 and 2020 titled Senderos de luz y sombras (“Paths of light and shadows”). A 16-channel piece commissioned by the French state, it looks to the origins of the universe and the unconscious mind for inspiration; as always, she’s drawn to the mysterious processes that animate life itself.

Its first half, “Senderos abismales,” begins with a slow crescendo that feels like being sucked into a vortex. Amid its agitated electronics is a familiar clatter, like that of a door being locked: a signpost for the way this music aims to entrap. The actual results are mixed. Ferreyra is at her best here when finding ways to ground her oblique electroacoustic cacophonies in the everyday, such as when gusts of wind and speeding cars sound like they’re rushing past you, their familiar sonics magnified to the point of being hyperreal. There’s a science-fiction affect to a lot of music in the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM) tradition, but if the music is constantly shifting, then it’s hard to feel immersed when every step of an evolution isn’t allowed to shine. In the middle of “Senderos abismales,” revving motor vehicles seem to materialize out of primordial goo, but they quickly fade to drab, droning hums. If Ferreyra’s fascination with the universe’s beginnings includes matter-antimatter annihilation, then she’s begrudgingly successful: Flashes of energy are indeed created, but they’re instantaneous, fleeting.

A lot of writing about Ferreyra’s music notes her time with Pierre Schaeffer, founder of the GRM, but her stints with Bernard Baschet—the late instrument builder and sound sculptor to whom this record is dedicated—are insightful too. Baschet, along with his brother François, were invested in constructing novel sounds, and pieces such as Iranon and Chronophagie have an exploratory sense of wonder. Ferreyra also dedicates Senderos to another experimental titan: Bernard Parmegiani. After hearing an unfinished version of Violostries in the 1960s, Ferreyra was emboldened: “Everything is possible,” she remembers thinking. Whether with tape music or instruments made from metal and glass, these artists’ works helped Ferreyra see that she could conjure entire worlds from relatively simple means.