The only essential moment on Stone, the sixth album by beloved metal transmogrifiers Baroness, arrives just four minutes after the record begins and lasts only 30 seconds. As the band reaches the end of the chugging chorus that anchors “Last Word,” its newest member, Gina Gleason, rushes ahead, her guitar line swiveling like some snaky Chuck Berry lead that coils so tightly it snaps, leaving her to reassemble the pieces in a rush of squealing notes. It is a perfect guitar solo, a thrill ride so disorientating you’re left to wonder where you are not just in the song but in the world.

Gleason’s paroxysm complete, Baroness retreat into a haze of tremolo guitars, reorienting themselves until they can return to the tune’s main premise—that is, a plodding and byzantine reflection on mortality that suggests the Foo Fighters for a particularly bookish biker gang. Neither “Last Word” nor Stone ever returns to the ecstatic heights of Gleason’s shuddering solo. By record’s end, you may wonder if Baroness can reach them at all.

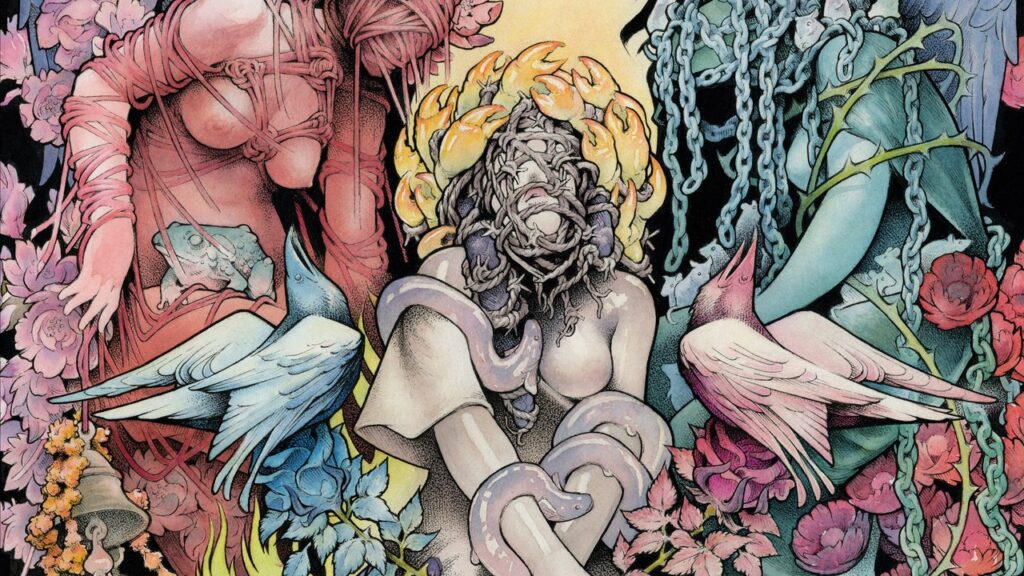

Baroness emerged in the mid-’00s as perhaps the most exciting and versatile band in a teeming renaissance of Southern metal. Leader John Baizley paired his strong-jawed stentorian bark with an unfailing sense of melody and real compositional ambition—think the Allman Brothers Band, Pink Floyd, and even Genesis, strained through the malevolence of swampy Southern forebears like Eyehategod. Even as the lineup often shifted, they made stepwise career moves, signing to genre bastion Relapse for a series of stunning records. After a devastating 2012 bus crash splintered the lineup, Baroness regrouped, launched their own label, and pursued slightly more commercial impulses, meting out eccentricity inside wildly accessible songs. “Shock Me,” the Grammy-nominated powerhouse from 2015’s Purple, should still be a radio staple, as should “Tourniquet,” from 2019’s Gold & Grey. At multiple points during the last 15 years, Baroness seemed on the verge of becoming a very big rock band.

But Baroness decided to downsize for Stone, their first album in four years, converting an Airbnb along the mountainous edge of Pennsylvania and New York into a studio where they could do everything themselves. This marked the first time that the same group of musicians who recorded the prior Baroness album reconvened to make the next one. Stone, however, begs for an outsider’s input, for someone to have said, “No, that’s not it.” So much of Stone feels like stitched-together composites of what has worked well in the past. Momentum is often squandered, and the electrifying bits rarely rise into something more.

Several minutes after Gleason’s blessed solo, for instance, “Last Word” wanders into a repetitious wash of electric jazz, as if Baroness didn’t know where else to go. These individual pieces are interesting enough, sure; note for note, Baroness remain one of the most remarkable and capable bands at the intersection of heavy metal, hard rock, and psychedelia. But this is Baroness as disjointed prog, their songs now composed of rusting spare parts that don’t work together. “Anodyne” is a pouncing rock song, its four-on-the-floor march boosting a tremendous Baizley hook. As it dips and dives into assorted breakdowns, bridges, and solos, however, Baroness never capitalize on their own might, never overwhelm or even exhilarate. Then it just stops, as if both tape and ideas simply ran out.

Baroness do try a few novel sounds, but they don’t fare much better. Early on, they devote a quarter of the album to a three-song suite that may be the nadir of their career. A ringer for an overly fussy Clutch jam, “Beneath the Rose” slams into “Choir,” a laughable spoken-word tale about Satan’s mistress murmured above an elementary Motorik improvisation. The triptych ends, mercifully, with a minute-long folk farewell that might have made a lo-fi Shrimper Records mixtape in an off year. You can almost picture Baroness in their Appalachian Airbnb, throwing things at the wall just to pretend they stuck.

The songs get stronger toward the end. With its forlorn acoustic preamble slowly yielding to shout-out-loud aplomb, “Magnolia” summons a frail body slipping into extravagantly engraved armor, formidable but delicate in the way Baroness’ best songs have always been. “Under the Wheel,” written by bassist Nick Jost, takes a similar dynamic path from somber to stomping. But its textures—crosshatched dissonance, fluttering falsetto, preening basslines—feel fresh for Baroness.

Even the acoustic closer, “Bloom,” is a corrective for the six-string bauble that begins Stone, a placeholder that even Baizley admits was little more than a mood-setter. “I lost my scepter/I lost my wings,” Baizley and Gleason coo in this sweet little country hymn of mortal homecoming. “Leave me a simple life.” By the time a gentle noise collage marks its end, Stone feels like you’ve sat through a half-hour mixtape of Baroness’ past flotsam just to arrive, possibly, at a 15-minute suggestion of its future.

Baizley often contemplates oblivion and the end during Stone, with bells tolling and suns setting and pyres burning. But near the close of “Under the Wheel,” the album’s clear winner, he sings, “So take the best of us/And burn the rest,” stretching the syllables into an unexpected hook that feels optimistic, as if he looks forward to the serotiny that can come with fire. There is at least a hint of hopeful concession there, of rising above some temporary station by recognizing something’s got to change. Now they just have to set flame to the pieces of the past they no longer need.