Like his friend and colleague Julius Eastman, Arthur Russell was an artist with no spiritual homeland. He was a composer who made pop music, an introvert who haunted discos, an Iowa native who was neighbors with Allen Ginsberg. Also like Eastman, Russell has proven slipperier the harder we’ve grasped for him. No matter how many unheard works emerge from the vaults, there is the sense that we will never truly know him. Whether it’s country, dance-pop, or cello improvisation, a serene inscrutability beams out at you from his music, his only true signature.

The person who knew Russell most intimately was his partner, Tom Lee, and our vision of Arthur Russell, however spectral, is largely a product of his work. Russell was widely admired in his lifetime but only managed one studio album—1986’s World of Echo—and never took full advantage of his connections to figures like Ginsberg or Philip Glass. After Russell’s death from AIDS in 1992, Lee tasked himself with sorting through the thousands of poorly labeled tapes Russell left behind. Working with Steve Knutson of Audika Records, Lee has fleshed out Russell’s catalog with extraordinary care.

The albums that Audika has released—including masterpieces like Calling Out Of Context, Love Is Overtaking Me, and Iowa Dream—have redefined what it means to tend to a musical legacy. Each release feels like a coherent piece of a larger picture—a remarkable feat, considering that it doesn’t seem to be at all the way Russell worked. He never stopped working on music that always sounded unfinished, switching endlessly between projects. But Lee and Knutson have taken his unruly, wide-ranging muse and transformed it into a catalog. The result feels less like a discography than a neural map of Russell’s creative process.

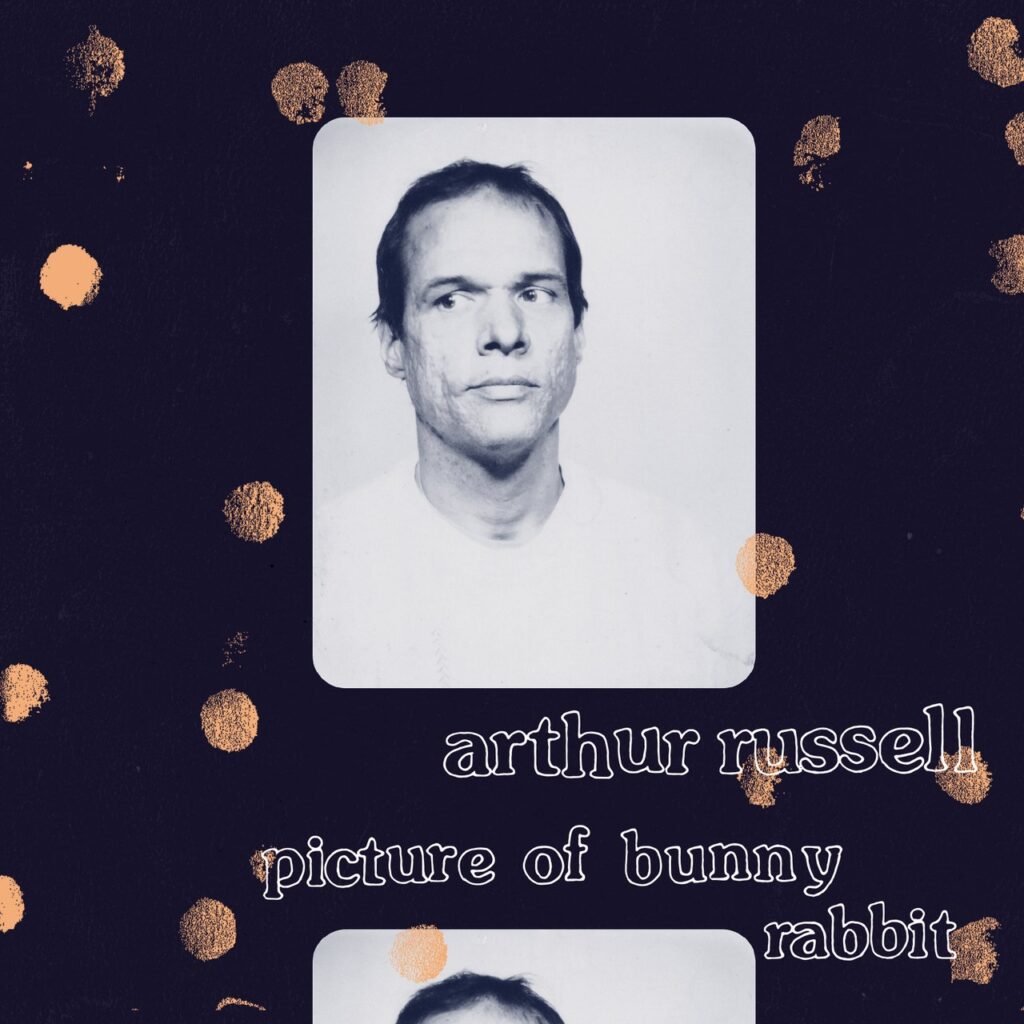

For evidence of their grace, consider the fact that the pair waited until 2023 to release this. The nine pieces on Picture of Bunny Rabbit closely resemble the by-now-hallowed World of Echo, both in sound and in spirit. Russell wrote and recorded many of the pieces in the same sessions, and they feel like an extension of that album’s haunted, lunar sound world, with Russell’s voice and cello sending lonely ripples out to die on an ocean of reverb. Picture of Bunny Rabbit offers the chill of encountering more of a beloved artist’s classic work in the moment they made it.

There’s something near-holy about overhearing Russell in this magic half-light again. This was the first atmosphere in which many of us first encountered him—dust motes spinning slowly in light, air stilled, his voice and cello the tenor of murmured prayers. You can almost never make out precisely what Russell is saying, save for alluring phrases that come through crystal-clear: “The very idea,” from “Telling No One,” or “It’s the only day” from “Not Checking Up,” a song in which Russell seems to mumble dreamily about watching an old loved one from afar. Russell was enraptured by ambient sound—blenders, buses, subways, whirring fans—and it seemed important to him that his music fold into the hum of everyday life. “Do you want to know who this person is?” Russell sighs on “Very Reason,” before drifting away again. His music is like a fish tank, his voice swimming mutely by, fixing you with its wide unreadable eye.

When we listen to Picture of Bunny Rabbit, we hear Russell as Knutson and Lee hear him, and many works on the album bear the unmistakable mark of their co-creation. The numbered “Fuzzbuster” pieces that break up the tracklist come from a test pressing unearthed by Russell’s mother and sister. They fit intuitively, like Terrence Malick shots of clouds and sky in between dialogue. “In the Light of a Miracle” is a stunning creation, and it wouldn’t exist without Knutson, who edited and shaped its sublime seven minutes out of a much longer improvisation. Who knows how many unproductive hours and minutes Knutsen logged listening to these tapes before his ears perked up: the bouncing bow pattern, the high vocal melody, seemingly calling from across a distant hill. But the piece, as it exists here, is an exalted clearing, a revelation among a discography of revelations: “Holding in the light/Reaching in the light,” Russell repeats, his voice dancing like a wisp out of your peripheral vision.

For Russell, World of Echo was just one tributary in a vast river of music. It was one mode, one style. He didn’t make academic distinctions, and he didn’t make emotional ones, either—his dance music is suffused with the same unearthly longing as his composed works. All of his work pointed to the same luminous spot in the distance—a hazy glowing light that it seemed like only Russell could see.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.