When Anjimile was a senior in high school, their conservative Presbyterian parents caught them emptying the household liquor cabinet. In response, they took Anjimile to church every week, even sent them to Christian counseling, hoping that the rebellious teenager would catch some religion and see the error of their ways. It didn’t take. But in that process, Anjimile discovered a newfound love for the words in the King James Bible, particularly its invocations of divine love. 2020’s Giver Taker—written in the early days of their recovery from alcohol addiction and at a time when they were still coming to terms with their gender identity—is littered with liturgical references and hymnal harmonies, as Anjimile draws on the vocabulary of their former faith to tell their story of survival, resilience, and spiritual rebirth.

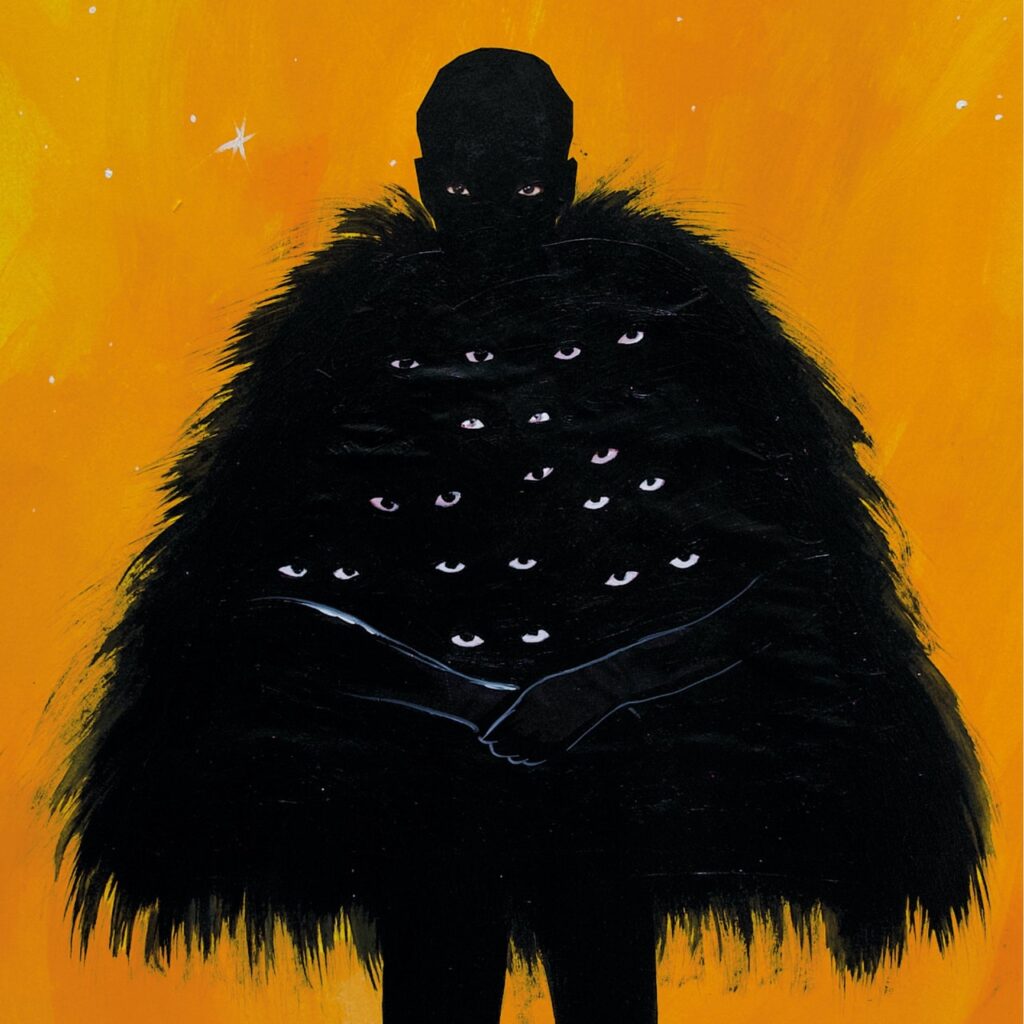

Anjimile turns to the Bible again for follow-up The King, but this time they’re channeling the righteous fury and fire-and-brimstone vengeance of Old Testament apocalyptica. Written during times of intense persecution, Jewish and early Christian apocalyptic writings represented a “literature of the oppressed,” their message of divine retribution particularly appealing to those who saw no hope for redemption in earthly politics. Anjimile taps into similar feelings of hopelessness and despondency—and a yearning for catastrophic justice—on The King, offering up an unflinching portrait of the anger and grief that comes with being Black and trans in an America that remains lethally dangerous for both.

The opening title track sets the tone with needle-sharp arpeggios strobing in the sky like a celestial sword fight. Anjimile invokes the Old Testament story of King Belshazzar and Daniel in a stinging indictment of the arrogance of American white supremacy. “Your silence a stain/The marking of Cain,” they hiss, throwing Biblical condemnation back in the faces of those who used religion to justify the enslavement of Black people. “Judge and Genesis/Make an end of this,” they plead on the grief-stricken “Genesis,” written in the wake of George Floyd’s lynching by four Minneapolis cops. It’s hard to tell whether they’re asking for personal deliverance or millenarian Armageddon. The raw, stinging guitar solo that closes out the track is heartbroken enough to suggest either possibility.

Anjimile plumbed depths of personal and generational trauma on Giver Taker—hitting rock bottom in a hospital bed, grappling with the homophobia and transphobia they’d faced from family—but that record was buoyed by gratitude for their newfound stability, for the simple fact of their survival. The King, not so much. Working with producer Shawn Everett, Anjimile strips away all that was bright and airy in their sound—the sunlit piano chords, the shimmering synths, the bouncy African polyrhythms. In its stead, there’s just Anjimile’s voice and some modified acoustic guitars. They use these two building blocks, and an array of innovative effects, to create an entire cosmos of sound, maintaining an atmosphere suffused with dread even as the individual compositions move between post-rock grandeur, sepulchral dirge, and sepia-tinged folk.

“Harley” drenches Anjimile’s finger-plucked guitar in layers of reverb, each note ringing out as a lonely echo in the murky darkness. The bit-crushed guitar lead of “Black Hole” sounds like an acoustic wave disintegrating under the pull of interstellar gravity. The jagged, marching chords of the scorching police-brutality protest anthem “Animal” sound like something Pretty Hate Machine-era Trent Reznor would have dreamt up, if forced to trade his synths for an acoustic guitar. The meaty menace of those chords throws in stark relief the hard-fought restraint of Anjimile’s vocals, as they sing of the dehumanizing rhetoric of white supremacy and its corrosive effect on Black consciousness (“If you treat me like an animal/ I’ll be an animal”).

There are a handful of moments of grace and gratitude, like the soothing croon and intricate finger-plucked guitar of “Father,” a song about the support Anjimile received from their parents when they entered rehab. But even parental love does not remain untouched by the darkness. “Am I your son? Could I be one?” they tenderly inquire on the expansive, post-rockish “Mother,” a gut-wrenching portrayal of the bewildering sense of rejection caused by their parents’ transphobia.

The King offers no light at the end of the tunnel, no promises of inevitable redemption. Grief and anger only give way to more grief and anger. What it does offer though, is an invitation to feel deeply, even—especially—the heartbreak, fear, and anger familiar to not just American Black and trans youth, but anyone whose identity has made them a target, left them feeling hopeless and powerless. Anjimile tells you to accept your suffering, not run away from it, lest your unattended wounds drag you into the abyss.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.