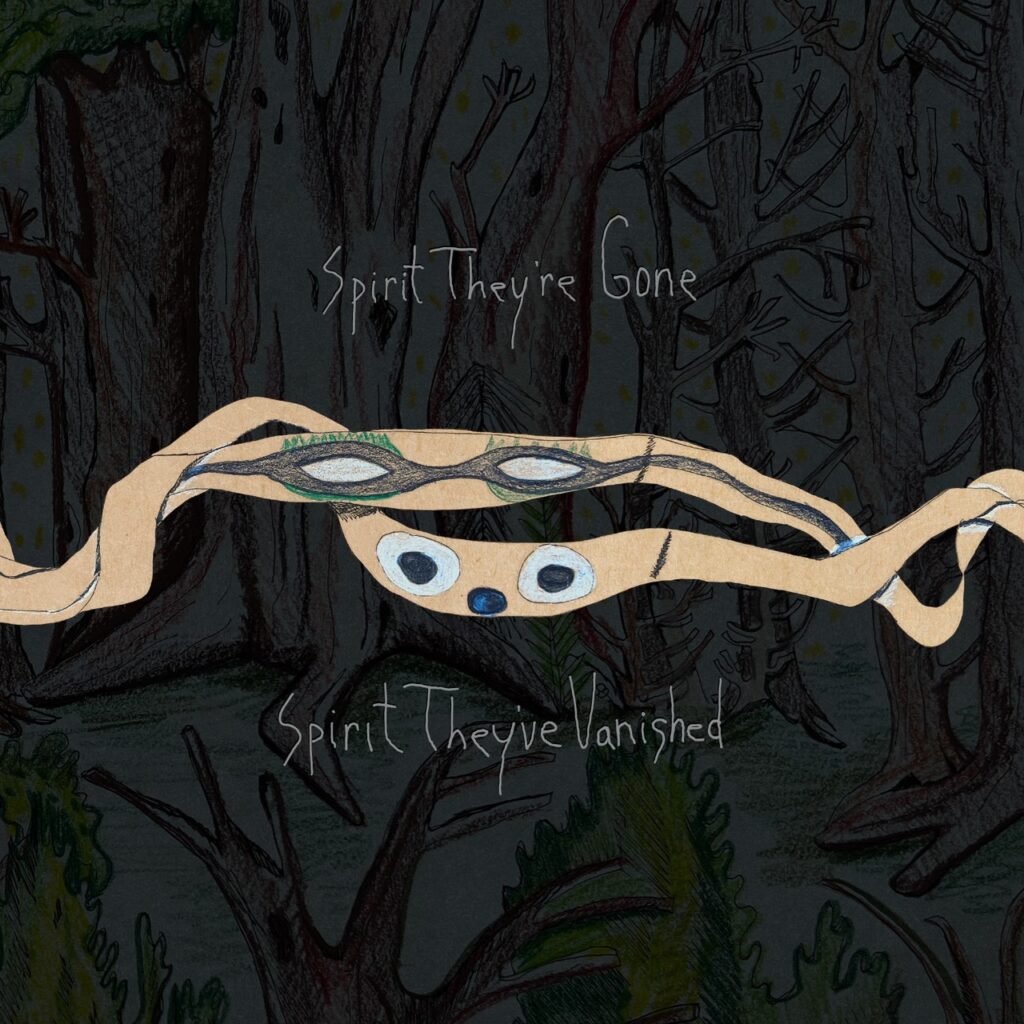

You probably know the story of Animal Collective, the band that started out making electronic-acoustic noise jams with lots of babbling and screaming, gradually learned to pull melodies and song structures from the iridescent muck, and eventually became indie-rock stars. Spirit They’re Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished, self-released in a tiny edition of CDs by the duo of Dave “Avey Tare” Portner and Noah “Panda Bear” Lennox in 2000, and now remastered and issued alongside an EP of previously unheard tracks from the same period, doesn’t quite fit that tidy narrative. Animal Collective’s de facto debut is a far more deliberate, ambitious, and even sophisticated album than a listener working their way backward through their catalog might expect, given the music that came soon after.

The likes of 2001’s Danse Manatee and 2003’s Here Comes the Indian (later retitled Ark) can give the impression that the band in its early years was driven mostly by intuition and enthusiasm, summoning whatever ecstatic racket their limited tools and proficiency would allow. But as is so often the case with artists who are labeled childlike outsiders or savants, it seems at least as likely that they cultivated their primal sensibility on purpose, because they were interested in its expressive and aesthetic possibilities. Revisiting Spirit They’re Gone two decades and 10 or so albums later makes clear that Animal Collective were not a bunch of naifs who donned silly names, twisted a few knobs on their SP-404s, and landed dizzily in the art-pop avant-garde. From the beginning, they knew what they were doing.

The subsequent Animal Collective release that Spirit They’re Gone most resembles is 2005’s Feels, in that it is more or less a rock album, albeit a highly idiosyncratic one. Portner and Lennox recorded it at Portner’s parents’ house, when both were just shy of drinking age, with future bandmate Josh “Deakin” Dibb engineering. Portner sang and played guitar, piano, and various electronics; Lennox played drums. The songs are long and elaborate, with dramatic dynamic and rhythmic shifts, more like progressive rock than anything else in their catalog. Portner’s lyrics reflect on childhood and look apprehensively toward what comes next, rendering the adolescent journey in imagery befitting a fairy tale.

The story goes that Portner had originally envisioned making a solo release, but was so moved by Lennox’s contributions that he gave him co-billing. It’s easy to understand why. Lennox’s drum parts are as important to the album’s uncanny atmosphere as Portner’s vocals. They often sound like the fills most rock drummers use to punctuate a section or transition from one to another, tumbling across toms and cymbals to build tension before locking back into the beat. But Lennox didn’t use them that way. Instead, he repeated these ornate sequences over and over, so that an entire six-minute song might live in the transitory moment of a drum fill, forever on its way. It’s a fitting technique for an album so focused on the passage of time.

Such active rhythms might overwhelm the songs or oppress the listener if it weren’t for Lennox’s light touch. He plays more like a jazz drummer than a rocker, landing hits like drizzle on a tin roof. Anyone who primarily associates Animal Collective with the pounding of a single floor tom may be surprised at how skillfully he finesses the kit here. His crucial decision to use brushes rather than drumsticks was apparently guided in part by the pair’s mutual appreciation for Love’s 1960s psych-folk landmark Forever Changes, a choice that points obliquely toward Animal Collective’s more mature work. Part of their greatness lies in the ability to absorb outside influences, assimilating rather than replicating them; Spirit They’re Gone sounds no more like Love than later albums sound like Frankie Knuckles or the Grateful Dead. Nor, for that matter, does it sound much like free jazz or reggae, despite the distinct imprint of the former on the stormy introduction of “Alvin Row” and the latter on the synth basslines across the album. The similarity to Jamaican music is most pronounced on “Chocolate Girl,” when that song’s initially jittery rhythms downshift into loping half-time for the chorus, and for a moment Avey Tare and Panda Bear are grooving just like Sly & Robbie.

Those faint glimpses of influence on Spirit They’re Gone are the exception. More often, the album is striking for how singular it sounds. How were these 20-year-olds, without the resounding validation that would come later, already so confidently in command of their own ideas, especially when their ideas were so strange, so free from received notions about how rock bands should operate, so feral, so potentially uncool? Which record in Portner’s collection could have possibly inspired the section of “La Rapet” when the drums fall away and all that’s left is a lonely acoustic guitar, a sound like crumpling paper, and his queasily pitch-shifted voice, cooing and sighing like a toddler? It’s the sound of Sung Tongs in miniature. What about their habit of adorning Spirit’s otherwise delicate arrangements with screeching, grating, headache-making high-frequency noise, somehow made beautiful by its surroundings? Pick almost any later album and you’ll hear some version of this impulse. And what made them so sure that such outré inclinations could share space on the same album—the same song, even—with music like the coda of “Alvin Row,” surging and heroic and easy to love, the sort of communal gesture that would eventually take them to the big stage? They started playing it live for the first time 16 years later, as if they wrote it with the future already in mind.

There are puzzling small decisions, perhaps indicative of the band’s lack of experience, that I imagine they might go back and change if they could. The omission of a bass part on “Penny Dreadfuls” slightly undermines its otherwise expertly paced arrangement, depriving it of a certain heft and grounding. The band was still figuring out which passages would begin to levitate with repetition and which would be better off played just once, and Portner’s surrealist poetry yielded the occasional awkward line, a combination that means “Bat You’ll Fly” ends with a full minute devoted to the chanted couplet “I feel so elusive in Houston/You feel so exclusively Houston.” Lennox abandons his restraint behind the kit for the final section of “Chocolate Girl,” and his copious cymbal crashes temporarily break the stillness of the album’s atmosphere, so that it sounds for a few moments like what it really was: a document of two young men jamming in a bedroom, rather than a transmission from a magical netherworld. The remastering job makes the album as a whole sound a little bigger and more present, but it can’t really fix issues like these, which is just as well. Part of the reason to reach for Spirit They’re Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished when you might otherwise play Feels or any other Animal Collective album is that sense of messy youthful aspiration and yearning.

The reissue also reveals another Animal Collective trademark already in place at this early stage: the quietly arresting album–companion EP. Five previously unreleased songs, collected under the title A Night at Mr. Raindrop’s Holistic Supermarket, reflect the themes of Spirit They’re Gone through an electronic funhouse mirror, replacing Lennox’s skittering percussion with dreamy sample collages and drum machines. The original songs, including a trancelike rework of “La Rapet” and an untitled track that presages the swampy synth ambience of Strawberry Jam, are good to great. The most interesting track for historical purposes, though, is a cover of Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams.” The arrangement reimagines the soft-rock classic as buzzing DIY dub, but otherwise it’s faithful to the original. A selection from one of the slickest and biggest-selling albums of all time seems an odd choice for this band, whose next few albums would approach pop the way an alien might approach a turkey sandwich. Maybe they knew bigger things were on the way.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.