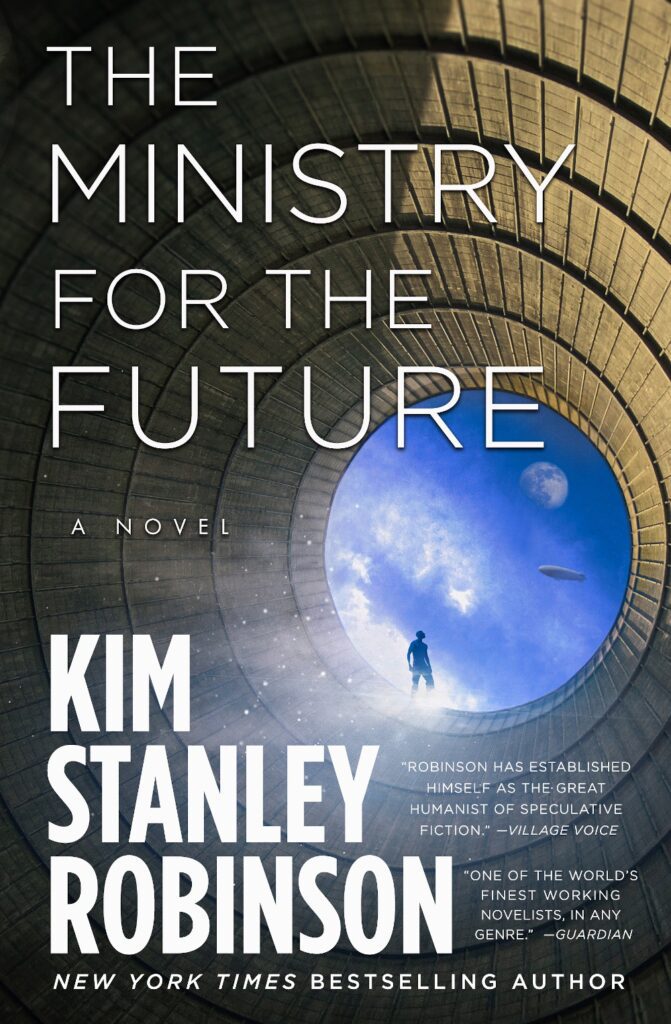

Who knew that in this dark hour of the climate crisis hope would arrive in the form of a 563-page novel by a sci-fi writer best known for a trilogy about establishing a human civilization on Mars? But alas, that’s what Kim Stanley Robinson – the author of 20 books and one of the most respected science fiction writers working today — has given us with The Ministry for the Future. It’s a trip through the carbon-fueled chaos of the coming decades, with engineers working desperately to stop melting glaciers from sliding into the sea, avenging eco-terrorists downing so many airliners that people are afraid to fly, and bankers re-inventing the economy in real time in a desperate attempt to avert extinction.

Robinson has a geeky, exuberant imagination and likes to pick up pieces of the world and examine them like a geologist examines rocks. In the novel’s 106 chapters, he riffs on blockchain technology, Jevon’s Paradox, carbon taxes, ice sheet dynamics, quantitative easing, among other things. He pays a lot of attention to how money moves around in a carbon-based economy, and may understand the financial underpinnings of the climate crisis better than any writer I’ve encountered. But he’s not afraid to get weird: He writes short chapters from the point of view of a carbon molecule, a photon, and a caribou.

He also has a compelling heroine in Mary Murphy, an Irish ex-diplomat who runs a Zurich-based UN agency called the Ministry for the Future (thus the title of the book), who is up against corrupt politicians and petro-state billionaires. In the aftermath of a horrific heat wave that kills 20 million people in India – Robinson describes thousands being “poached” in a lake where they fled to escape the heat — the Ministry sponsors various technological tricks to try to slow the warming, including dyeing the Arctic Ocean yellow so it stops absorbing sunlight. But the real drama is Murphy’s confrontations with a handful of central bankers around the world who help break the petro-billionaires and shift the economy away from fossil fuels. Meanwhile, debt strikes by students and uprisings by migratory workers send millions of people marching in the streets. It all feels plausible, in a holographic, sci-fi kinda way. In the end, Robinson achieves something unexpected: He transforms the existential crisis we face into a modern fairy tale of resilience and redemption.

Rolling Stone talked to Robinson about the role of science in a sci-fi novel, violence as a political tool, and why he thinks it’s time to buy out the oil companies.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Author Kim Stanley Robinson

Sean Curtin*

What was in your head when you sat down to write The Ministry for the Future?

I had written about climate before, but it was always offset into a future that was distant enough that there was a gap between now and then. I didn’t want the gap this time. I wanted it to start from now, go out about 30 years, create a plausible future history that was, to my way of thinking, a best-case scenario. But also one you can believe in. So that was the goal going in. And I did want to suggest that despite the extreme danger that we’re facing, a good global response could dodge the mass extinction event. My whole notion of utopia has come down to just survival of the many species that are in danger. If we dodge the mass extinction event, we can cope with everything else that might happen later.

This book opens with a brutal heat wave in India that kills millions of people. What inspired you to start with that?

Well, I’m terrified that it will happen. And so it struck me that a slap to the face, a warning shot, might be a good way to begin. Because it’s just a reading experience, and I’m a novelist. But as a citizen, looking at the news about wet-bulb temperatures [a measure of heat plus humidity], I began to realize that the crowd that advocates for adaptation and says, “Oh, well if we get a 3-degree Celsius rise, we’ll just adapt to that. We can adapt to anything,” they were wrong on that. We actually might quickly hit temperatures that will cook people. When I understood what a wet-bulb temperature could do and how limited our ability is to adapt, and how power grids will fail, and then there will be mass death, well, it struck me the danger that we’re in needed to be emphasized.

As a nonfiction writer who writes about climate change, I’m interested in how you think about scientific accuracy in writing your novels. I mean, it’s a different standard than when you’re writing about terraforming Mars, right? With climate, you’re writing about the real future that we are inventing for ourselves here.

Yeah. I come at it as a novelist. I want, first, to write a good novel. And so what my aesthetic says to me is that a good novel is very engaged with the reality principal. I don’t believe in fantasy novels. The reality principal is that when you’re reading a novel and you come to something you say, “Yeah, that’s right. That’s the way life is.” This is what you read novels for, is that vibe, that feeling. And I want that.

So I try to stick to the sciences as closely as I can, even in my Mars novels. I don’t break the laws of physics. I don’t like fantasy. And I do live with a scientist. My wife [Lisa Nowell, a chemist with the U.S. Geological Survey] is really quite tough on my manuscripts in terms of accuracy and tone. And also, because of her I spend a life with scientists. I watch how they work. I watch how they think. I’m entertained by them. They strike me as funny people. And that’s good. I mean, lucky for me, right?

In the book, the heat wave in India is what galvanizes political action. It reminded me of a discussion I had years ago. I was out in the North Atlantic with some scientists and we were talking about what was going to wake people up to the climate crisis. And one said, “Well, when a big hurricane comes along and wipes out a major American city, then people are going to wake up.” And that was right before Katrina. And then we had Sandy, and Harvey. And nothing really changed. There was no great political awakening.

Well, in my novel, I make it very clear that these events happen, it galvanizes action, and then nobody changes and nobody does anything. And I’m very interested in this cognitive error in the human brain that people don’t believe it can ever happen to them until they’re actually getting hammered personally. And even then, you read about these people dying of Covid who are claiming it to be impossible as they die. Michael Lewis was writing about the federal government in his book The Fifth Element, talking about a town in Ohio that got wiped out by a tornado, and we went to the town 10 miles to the north and they were saying, “Well, it can’t happen to us. They’re in the tornado track and we’re not.” As if there’s such a thing as a tornado track. It’s amazing.

So I would agree with your observation that there’s no one event. That’s one of the reasons why I went to wet-bulb, the temperature deaths, the mass deaths that might happen. [That] might radicalize that one country long enough to wake people up. What I wanted to show was some places would get better, other places wouldn’t care, and that it really would take a full 30 years of concerted action. And so I kept coming back to the international agencies where we coordinate international diplomacy, and also the central banks. The idea that if investment capital will only go to the highest rate of return, then we are truly cooked. We’re doomed.

One of the striking things about your work on climate is that it is so deeply meshed in the financial system. There’s a notion among many people on the left that solving the climate crisis is incompatible with capitalism as we know it today. Do you share that idea?

Well, I am a leftist, an American leftist, and I’m saying just as a practicality that overthrowing capitalism is too messy, too much blowback, and too lengthy of a process. We’ve got a nation-state system and a financial order, and we’ve got a crisis that has to be dealt with in the next 10 to 20 years. So I’m looking at the tools at hand. Tax structures, sure. And essentially, I’m talking about a stepwise reform that after enough steps have been taken, you get to something that is truly post-capitalist that might take huge elements from the standard socialist techniques.

I mean, I’m a member of the DSA [Democratic Socialists of America]. I love the whole injection of progressive left into the Democratic Party. I loved Bernie. I love Biden. I love anything that looks to me like it’ll be fast and effective. So quantitative easing. The quantitative easing of 2008 is really suggestive. If that money were targeted, not given to the banks to do their usual stupid gambling of going to the highest rate of return. None of these mitigation projects are going to be the highest rate of return. They aren’t profitable as such. It’s just that they save the world. So I’m arguing [for] the kind of hyper-reformist platform. I take the tools that we have in hand, try to wield them from a leftist and an environmentalist perspective.

There is a lot of eco-terrorism and eco-sabotage in Ministry. As the urgency of the climate crisis grows, this seems likely to occur in the real world, too. What are your thoughts about violence as a political tool?

As a middle-class American, a privileged white, American man, advocating violence is an irresponsibility, because it’s other people that are going to get hurt by that. And also, my feeling is that even the violence would only be to try to jumpstart better legislation. Without better laws, the violence would just be pointless violence. And so when I wrote the book, I was trying to walk a fine line and say to people, “This kind of step is likely to happen.” Because there’s going to be people far angrier, who are at the sharp end of the stick, who’ve seen people die, who get radicalized and are going to do violent things that might be stupid violent things, or they might be quite smart violent things, depending on who’s doing it and what for.

And so to my mind, I think sabotage, which would be destruction of property rather than human beings, sure. But violence against humans? No. I would rather see the laws change fast, and do it by way of logic and reason. But we’re not very logical, individually or socially.

Is there a disconnect between the scenario that you put forward hopefully in the book and the one in your heart of hearts you think is going to play out in the real world?

Yes. But this [book] is a deliberate political act to continue to insist that if the best-case scenario came to pass, it wouldn’t be so bad. We could actually create a prosperous world of advocacy for everybody and keep all the animals alive. It’s technically possible, which is to say physically possible. So it’s a story that needs to be told.

And then my own personal opinions, they’re all over the map. They aren’t always very hopeful like that book is. But they’re also irrelevant. I’m just a bourgeoisie suburban house husband. What I think might happen is irrelevant to my political positions and my novels, because you can’t predict the future. I mean, I wrote a novel in which the Soviet Union was lasting for, I don’t know, it was set maybe a century or a half-century in the future. I published that novel in 1988. And so my sense of what can really be predicted is very — I don’t even think that’s what science-fiction novels are trying to do. We’re not trying to predict the future. We’re running scenarios for their current political lessons, if there are any.

The two aspects of your book that I find at once inspiring and maybe a little implausible are, first, the idea that the UN becomes a force for change. And second, you have a line in the book that says, “Legislation does it in the end.” In other words, that we will pass laws and legislation that will grapple with the climate crisis in a meaningful way.

Well, yes. But I will say this. Rule of law, as weak a reed as it is, is all we got. If we don’t have rule of law, if you were to say some virtuous eco-warriors were somehow to seize power and enforce a virtuous action. Well, no. That scenario doesn’t play. It won’t happen that way. So it’s rule of law or nothing.

You write a lot about geoengineering in Ministry – pumping water onto glaciers to slow the melt, spraying particles in the sky to cool down the atmosphere. A few years ago I wrote a book about geoengineering called How to Cool the Planet. I learned that most scientists talked about geoengineering the way they would talk about sex – it was not something they wanted to discuss publicly. That’s changing, slowly. It seems to me that, for better or worse, it’s inevitable that we’re going to try some of these large technological interventions. And the more open we are about it, the better we can understand the risks and science.

Right. I’m with you on that. I feel like the intense prejudice against the idea of geoengineering coming mostly from the progressive environmentalist left, where I am, is a category error and is not paying attention to the realities of the danger that we’re in. And sometimes they are false. This notion that whatever we do we’re going to get Snowpiercer or whatever, or it’s just an excuse for rich people to continue doing what they’re doing. Well some of that’s wrong, and you know this. You put dust in the atmosphere and five years later it’s gone. It’s an experiment that won’t go awry and kill the world. And then some of it is just outdated. The situation that we’re in now, niceties about protecting the feelings of the rich are going to be completely irrelevant if we are in desperate need. So it all needs to be on the table, like you said. Openly discussed.

But it’s also true that geoengineering is pretty incompatible with Green New Deal-thinking.

I feel like my job as a science-fiction writer is to press the point that making something politically incorrect when you’re in an emergency is a stupid move and isn’t paying attention to reality itself. And there’s so much conformity, there’s so much ideological conformity, but also conceptual ignorance. I love the Green New Deal. I love HR109 [the Green New Deal resolution introduced by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez]. That’s really a smart document. It’s not naïve. It’s not primitive. It’s a fully articulated plan that takes in a lot of social elements that are very smartly done. So this is not a naïve crowd. There’s something hubristic about the phrase geoengineering, and it looks like a Silicon Valley techno silver-bullet fix that is against the grain of the total program that the left is insisting on, which I totally agree with.

But on the other hand, I’m in a nice position. Being a science-fiction writer, I can say, “Wait. Let’s put everything back on the table.” I’m willing to say, “Look, nobody’s done a proper analysis of nuclear power. Maybe it’s a bridge technology and maybe we need the U.S. Navy to build our entire electrical grid.” I mean, I put that in Ministry. “And go with nuclear for another 100 years until we get the clean energy laid out.” Now that may be wrong. It may be that we bypass that moment, and that clean energy is so good, so cheap and so quantitative that there’s no need to mess with something as dangerous as nuclear. But it all needs to be on the table. There should be no pieties, no political truisms at this point.

With Biden about to become president, the dark days of the climate movement in America may be ending. How hopeful are you right now about the direction things are going?

Well, much more than I would’ve been if Biden hadn’t won. I’m hoping that there will be pressures and forces bigger than Biden and his team that will shove them in the right directions. I met John Kerry in McMurdo Station in Antarctica. He was Secretary of State. He had a month to go. It was December of 2016. And he was great. He gave an hour talk improvised after staying awake about 24 hours. I was really impressed at his grasp of the situation and his ability to synthesize and go to the most important points. But again, it’s not going to be an individual game, and the fossil fuel industries and the other big fossil fuel countries, the petro states, they’re all important too.

This is why I keep coming back to quantitative easing. You’re going to have to pay off the oil companies. You’re going to have to pay off the petro states. They’ll need compensation, because their fiduciary responsibilities and their national priorities for the power of their own nation states are intensely tied up with these fossil fuels. And so we’re going to have to pay to keep it in the ground. And so you can regard that as blackmail or you can regard that as just business as usual, as a stranded asset that still has a value to us by not being burned. I mean, it’s a real financial value. Saving the world has a financial value that needs to be paid, and so we call it quantitative easing. So I’m hoping that the ordinary mechanisms of the Democratic Party and the American government will mesh with the Paris Agreement.

You have faith that the Paris Agreement will reassert itself?

Yes. This is another leftist truism that isn’t true, that the Paris Agreement is irrelevant or meaningless or not good enough or whatever. It’s the framework by which we’re going to make all this happen. It’s a major event in world history. It is obviously toothless and it doesn’t call for enough and the voluntary commitments by the individual nation states are only about half of what’s necessary. But it’s what we’ve got. And to dismiss it out of hand, and then what’s the replacement? Instantaneous world revolution? I mean, give me a break. It’s so crazily idealistic where the perfect is being the enemy of the good.

The hardest thing to grasp about the climate crisis, and something that your book does so well, is imagining the totality of the transformation that needs to happen here. Sometimes I’m skeptical that we’ll ever be able to bend our minds around it.

Well, yes. But this is where I have a lot of faith in the novel as an artistic form. It’s very capacious, it takes in a lot of junk, it’s not a slim or efficient art form. It’s a baggy monster. And my novel is a baggy monster. But the novel is about the social totality. And what’s cool about being a science fiction writer is the planet is part of the social totality. It’s a citizen, it’s an actor in the actor network, it’s part of our body.

This is what I love about the responses to The Ministry so far, is people want a sense of their totality, which is clearly an imaginary act because the totality’s too big to be comprehended. But it can be imagined in novels. The novel is a 19th-century, old fashioned form that’s been superseded by the movies. Sometimes it looks like maybe its run its course like epic poetry, or plays in verse. But it’s not really true. People still read novels. And so as a novelist, I love that. And if it helps the political situation, then all the better.