The year Donald Trump was carried into office on a frothing anti-immigrant platform, there were an estimated 10.5 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States. Roughly two-thirds had been here for more than a decade. Prior administrations had abysmal records, but generally acknowledged that the U.S. was enriched by the immigrants who chose to build their lives here. It’s why Ronald Reagan granted amnesty to some 3 million undocumented immigrants, why George W. Bush supported a path to legal citizenship, why Barack Obama — labeled “deporter-in-chief” after removing nearly 3 million people — also created DACA to protect immigrants brought to the U.S. as children.

But from the start, Trump embraced a rabid xenophobia once restricted to the furthest fringe in modern American politics, slashing refugee admissions, rescinding DACA, and ratcheting up arrests of longtime residents. All of that was before the pandemic hit, shutting down immigration courts, turning detention centers into viral tinderboxes, and giving the administration cover to institute some of its most draconian measures yet.

A year ago, Rolling Stone began documenting the stories of immigrants around the country who are fighting removal, waylaid in detention centers or mired in endless court proceedings, with the stability and safety of their families hanging in the balance. (Last names have been withheld out of concern over retaliation.)

“There was a moment in the story when we were in a church in Mississippi for the celebration of a Quinceanera, filled with Guatemalans dressed in their traditional clothing,” says photographer Federica Valabrega, herself an immigrant from Italy. “All I could hear was their Mayan dialect, and I remember having chills. I felt so included and so close to the immigrants reciting prayers in their own dialect to keep their identity intact. I felt ‘we were all immigrants’ in a foreign country trying to make ends meet, while never forgetting where we came from.”

Along with video producer Reed Dunlea and writer Tessa Stuart, Valabrega documented people who’ve lived and worked in the U.S. for years — some with little memory of their birth country — who now face removal. Beto, a 25-year-old DACA recipient, was deported back to a country he hadn’t seen since he was nine. Ignacio, a father of three, may be forced to leave his family and the town he’s lived in for more than three decades.

But despite the administration’s best efforts to drive them away, these families share a determination to hang on to the lives they’ve made here. “What we want is the same as any Americans,” says Hormis, Ignacio’s wife. “We dream of buying a house, like anyone. We have a family, we have a dog. We’re hardworking people that love the country. That’s why we’re here.”

Here are those families’ stories.

Alfredo | Queens, New York

A family strains under the pressure of uncertainty as the father awaits a ruling on his removal

Alfredo, a cook in New York, is fighting an order of removal.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

In July 2018, Alfredo boarded a Greyhound bus in New York City bound for Seattle, to meet with his brother. “I was super excited,” Alfredo says. “It looked like we were going to have months of work.” But near Buffalo, New York, the driver announced that the bus was being diverted into Canada. “That’s when things started to make a turn.”

Searches of Greyhound and other bus lines by Customs and Border Protection increased dramatically in the first year of the Trump administration. An internal CBP memo called it an opportunity “the likes of which we have not seen in a decade,” and was signed, “Happy hunting!”

Alfredo, who had his Mexican passport and a driver’s license from Washington state, where he lived after first immigrating to the U.S. from Puebla, Mexico, without papers in 2004, was taken into custody by Canadian authorities, then sent to an ICE detention center near Buffalo, where he spent 20 days while his wife raised money for his bond back home in Queens.

Alfredo, 38, has since had a work permit approved, but he’s still waiting to find out if he will be deported; his next court date is not until 2021. Before the pandemic, he was working at a Mexican restaurant in Manhattan, but he doesn’t know if that job will ever come back. He says he feels depressed and unsure of his future, and that the ordeal has ended his marriage.

“With the stress of what was going on, she didn’t want to be involved with the case, so she kind of distanced herself,” Alfredo says. They share joint custody of their three kids: Eduardo, seven; Valentina, six; and Hector, five. “When I’m with them, I try to stay relaxed, not sort of transmit to them what’s going on — the emotion of what’s going on,” he says. But he can tell that they worry. “Whenever they see police, they hug me and say, ‘Oh, there’s cops over there, let’s go this way.’ It really affected them.”

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I try to stay positive,” says Alfredo, “mostly for the kids.”

Rosalína | Ossining, New York

A nanny contracts coronavirus as she fights for the return of her husband from Guatemala

Jorge and Rosalína are both from Guatemala, but they met and fell in love in Ossining, New York, a small village on the Hudson River where Jorge worked in a deli for 13 years. In 2008, they returned to Guatemala and opened a general store, but it wasn’t long before the threatening phone calls started — gangs demanding that Jorge deposit money for them into a bank account. “And that if he didn’t, the kids would pay,” Rosalína recalls.

The family crossed back into the U.S. on Christmas Eve 2016, seeking asylum from gang violence and extortion. Rosalína and the kids were allowed to go back to Ossining, where she works as a nanny, to await hearings, but Jorge was detained for eight months, then deported. In 2018, he attempted to cross again and spent almost two years in a Texas detention center, working as a cook for $3 a day, before he was deported in December. He’s in hiding in Guatemala, even as his asylum case is still being appealed.

Their daughter Angelica, 19, speaks to her dad often, but not about the gangs. “I don’t have the courage to speak about it,” she says. A grocery worker, Angelica contracted the coronavirus in March, at the same time as her mother. They have both recovered, but “it hasn’t been easy,” says Rosalína. “I know the kids are watching me, so I tell them we’ve got to keep going.”

Rosalína, a nanny, had to isolate from the kids she takes care of for months during COVID. Both she and her daughter, Angelica, 19, contracted the virus.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

Fredy | Carthage, Mississippi

After living in the U.S. for 18 years, a father is swept up in the largest coordinated workplace raid in ICE history

Fredy at his daughter Marleny’s quinceañera, a few months after the raid.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

Fredy was driving a bus in Guatemala some 20 years ago when the woman who would become his wife got on. “That’s where everything started,” he says. She came to the United States first; he followed on foot in 2002.

They settled in Mississippi, where he found work at a chicken-processing plant. “I started from the very bottom — in the area where they cut the breast in half,” he says, but worked his way up, becoming a janitor, then a painter, and finally a mechanic. That’s what he was doing in August 2019 when he and 679 other undocumented workers were swept up in the largest coordinated workplace raid in ICE history.

The day he was detained, he couldn’t stop thinking about his wife and four children, about his oldest daughter, Marleny, and the 15th birthday she had coming up. “In that moment, many things were running through my mind because my family was home and I didn’t know anything about them,” he says. “All my sons and daughters were born here. If we take them there, they are going to be immigrants like us.”

The raid ostensibly targeted the executives at seven Mississippi plants, but to date none of them have been prosecuted. An ICE official expects that all of the workers, including Fredy, who was released with an ankle monitor, will be deported. A few months after the raid, many of them gathered to celebrate Fredy’s daughter’s quinceañera. “Even though we are going through tough times, the best solution is to come together, spend time together, and forget our sorrows,” he says.

Fredy’s final hearing was set for June, but Rolling Stone has been unable to contact him since early spring, around the same time COVID-19 swept through his community — dozens of cases were reported at the same plants raided months earlier.

Back in November, Fredy said he hoped the Trump administration realized it was wrong: “They left a lot of children without parents. With our kids, we can give back. A doctor, a lawyer — our daughters and sons can become that. If we have done something wrong, it was not because we want to take from your country, but because we want to give something good.”

“Even though we are going through tough times, the best solution is to come together, spend time together, and forget our sorrows,” Fredy said of Marleny’s quinceañera.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

Beto | Chicago, Illinois

A birthday hiking trip turns into a nightmare for a former DACA recipient

Beto, a construction worker from Chicago, in custody in Iowa before being deported.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

“Fresh air — that’s what I miss the most,” Beto said from behind the glass at the Hardin County Jail in Eldora, Iowa, back in February. Over the previous nine months, he’d lost 30 pounds as he bounced between three different county jails that had contracts to hold ICE detainees.

Last May, he and three friends went hiking in Colorado to celebrate his 25th birthday. Beto, who arrived in Illinois from Guadalajara, Mexico, with his parents on a tourist visa when he was nine, was napping in the back seat on the drive home when the car was pulled over for speeding.

They were booked for possession of marijuana, but the charges were soon dropped. His friends were citizens: “They went home. I didn’t go home,” he says. Beto had been a DACA recipient, but when the Trump administration rescinded DACA in 2017, his status was thrown into limbo. With support from his community in Chicago, Beto made bail. But in June, in the midst of the pandemic, he was called back to Iowa for a hearing. If he failed to show, he was told, his $25,000 bond would be forfeited and a warrant would be put out for his arrest.

Beto was detained at the hearing, transferred to Nebraska, given a flimsy mask for protection, put on a plane to Texas, then driven across the border to Reynosa, Mexico. From there, he had to find his way to an uncle in Guadalajara, more than 600 miles away. Just one week later, the Supreme Court declared that Trump had ended DACA illegally. “It’s a place I don’t recognize,” he said on the phone from Mexico in June. “I’ve been trying to adapt, but it’s difficult. My life belongs over there, with my parents and my family.”

Ignacio & Hormis | Wolcott, New York

A married couple — one a citizen, and one undocumented — fights to keep their family together

“The government treated him like a criminal when he hadn’t done anything but work,” says Hormis.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

Ignacio came to the United States some 31 years ago, on foot through Tijuana, when he was just 18. “I don’t remember much about Mexico,” he says, now 49. But he does remember when he first met Hormis. She arrived from Mexico at the apple orchard where he worked in 2003. They married two years later, settled into the steady rhythm of life at the orchard that they now supervise, and had three sons.

In December 2016, Ignacio was putting the kids on the school bus when he noticed a black sedan parked a few doors down. It was ICE. “The kids got back from school and asked where their dad was,” Hormis says. She told the oldest child the truth, but initially kept it from their two younger sons: “I had to lie and tell them he had gone to work someplace far.”

Released after six months on $15,000 bond, Ignacio was given an order of removal; the family is appealing and also applying for a green card based on his marriage to Hormis, who became a citizen in 2017. If he’s deported, she and their sons will stay in Wolcott. But it won’t be easy without him: When COVID struck, Hormis had to cut back hours at the orchard to home-school the kids. “I tell them not to worry,” says Ignacio. “I might not be there, but they’re in my heart, wherever I am.”

Suyapa | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A domestic-abuse survivor gets a visa after two years of hiding, and emerges to a pandemic

In her room at First United, with her sons Junior and Jeison. “People in the church are supportive,” she says.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone

For 562 days, Suyapa and four of her children lived on the second floor of the First United Methodist Church of Germantown in Philadelphia. She came to the United States in 2014 after her oldest daughter was granted asylum. A victim of domestic violence, Suyapa, 38, had applied for a special visa, but ICE refused to defer her deportation while the application made its way through the system. That’s why the family sought refuge inside the church. She just didn’t expect to be there as long as she was.

“It’s not so easy being in the sanctuary — the girls are closed in,” Suyapa said in September. “God gives me strength. People in the church are supportive.” Once a month, Suyapa cooked dinner for the parishioners; she hopes to one day open a Honduran restaurant.

On March 12th, Suyapa’s visa was finally approved, and she left First United for the first time in nearly two years — just as the country was going into lockdown for COVID.

Almost immediately, Suyapa got sick with symptoms of COVID. She recovered, but amid the economic crisis, she’s struggled to find work. “I feel safe,” she says. “It’s just when the rent is due, I start to worry.”

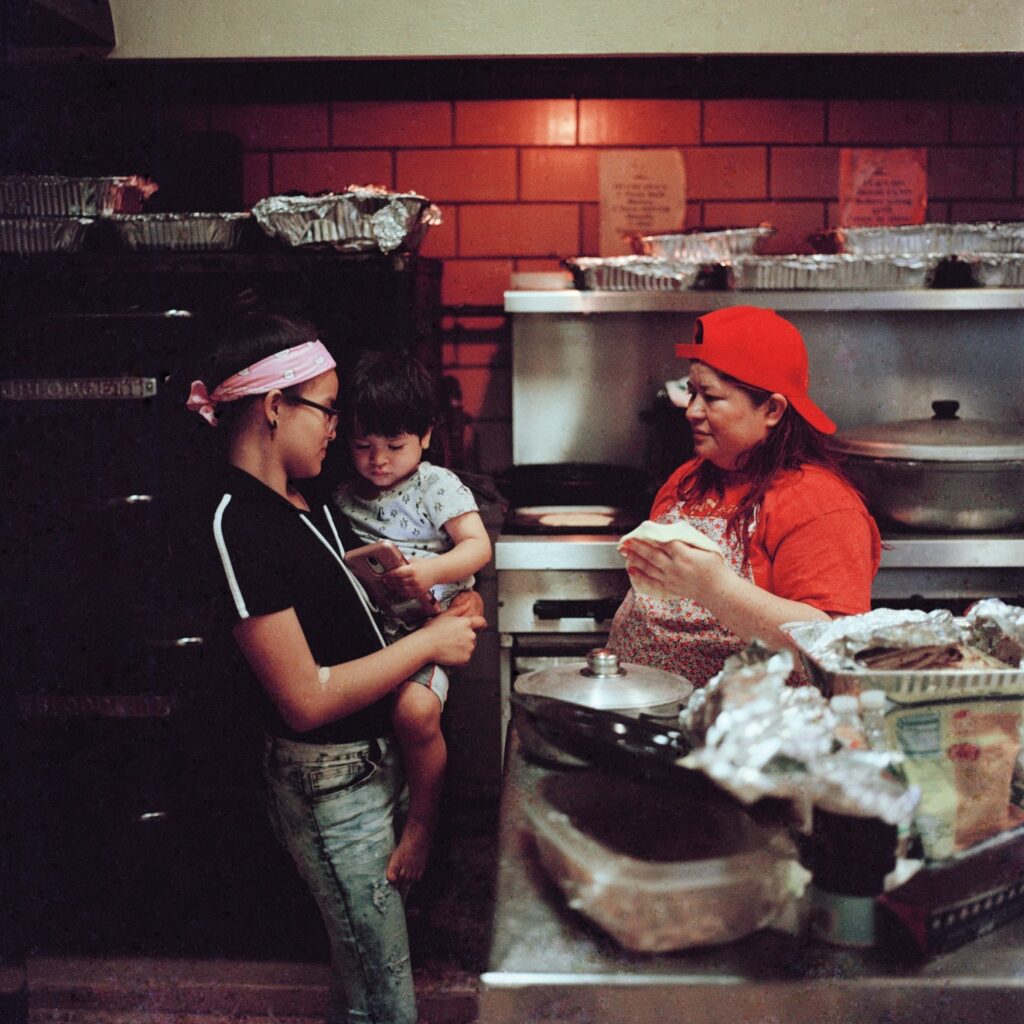

Suyapa, who would cook for the parishioners once a month, dreams of opening a Honduran restaurant.

Federica Valabrega for Rolling Stone