There’s an ancient Chinese proverb that parents like to tell their kids whenever they start getting angry or worked up. It literally translates to “A quiet heart will naturally keep you calm and cool.” The idea, in Asian culture, is that it’s better to keep your mouth shut rather than to cause a fuss, for fear of attracting unwanted attention on yourself — or your family.

I still vividly recall a moment when I followed that maxim, already so firmly ingrained in me. I was seven years old when two white classmates tripped me up in the schoolyard during recess, and proceeded to punch me in the back of my head as I folded my undeveloped body into the ground for protection. Twenty minutes later, I was standing up, forced to face the wall of my classroom as our teacher held me for detention, having been convinced by the bullies that I was to blame for the fight. “You shouldn’t have provoked them,” she said, with a shake of the head that at once expressed disgust at my actions while simultaneously freeing the other boys to leave the room scot-free.

I wanted to speak up and defend myself, but between the tears on my cheeks and the welts on my body, I was too bruised and too scared to know what to do — or what to say. And so, I did the most Asian thing that I could think of: I apologized.

“I’m sorry I made them angry,” I said, through stuttered sobs. “I won’t do it again.”

I knew apologizing would make the situation go away, even if it didn’t make things right. But in that moment, facing the alabaster walls of my grade-school classroom, I had never felt more ashamed of my silence — or more alone.

With the recent rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and violence against the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community, many cultural leaders, educators, and advocates have urged us that it’s time to reject what we’ve been taught, and start speaking up — and fighting back — against the hateful rhetoric and injustices brought upon the community.

Rolling Stone spoke to six Asian American leaders to discuss the wave of anti-Asian sentiment in the country, the long-held stereotypes we need to overcome, and the steps we can all take to ensure that Asian voices are no longer buried but, rather, at the forefront of change.

We’re done apologizing. And we’re done staying silent. Here’s how Asians — and their allies — can start using their voices to take action, demand justice, and shatter the “model minority” myth once and for all.

Anti-Asian racism is nothing new. Why do you think it’s finally getting more attention in the press and mainstream these days?

Lin Chen (CEO and founder of Pink Moon): I think many, many factors contributed to the mainstream acknowledgment of Asian suffering. Covid-19 was introduced into an already hostile sociopolitical climate in the U.S., which caused many to react violently or aggressively towards Asian folks. The spike in racially-motivated attacks and hate crimes rose dramatically as a result, and because of social media, people took notice, even when the mainstream media wasn’t covering the incidents. Over time, the mounting number of hate crimes and awareness on social media forced mainstream media to pay attention.

Barbara Jean Reyes (poet, writer, and professor): I think the fast answer to this question is “China Virus.” Asians have been scapegoated in American history for economic catastrophes, for polluting American cultural and racial purity, and when “China Virus” became something those in power spoke into our current context and posted on social media, then Chinese people, and by extension, Asian-appearing people in this country, became the scapegoats for the pandemic, for all the illness and death, joblessness. Americans have historically ridiculed Chinese people for all the “weird shit they eat,” so when news emerged of the coronavirus coming from bats, how easy was it for Americans to come back out with these stupid jokes?

Casey Mecija (assistant professor at the Department of Communication Studies at York University): The rise of anti-Asian violence emerges in a political climate where Chinese people have been blamed and targeted for the Covid-19 pandemic. Trump’s unyielding anti-Asian sentiment, in particular, his attacks on Chinese people, have fueled, if not condoned, anti-Asian violence. So, this is a moment where anti-Asian violence is being exposed on the heels of a devastating pandemic and in the midst of ongoing violence against black people.

“Anti-Asian racism is having a moment of cultural currency, but ‘we’ know that it’s always been here.”

What role has social media played in the ability to amplify the anti-Asian attacks, but also amplify Asian voices in response to these incidents?

Reyes: Social media has allowed us to document incidents of violence otherwise dismissed by the mainstream, when it was individual Asian people’s testimonies versus an immovable block of American righteousness and exceptionalism. In this age of surveillance, all of the footage of us going about our lives in public spaces is admissible evidence. But so many Americans still want to believe these are always isolated incidents.

Mecija: Anti-Asian racism is having a moment of cultural currency, but “we” know that it’s always been here. Social media is forcing confrontation with images, videos, and news headlines that are being circulated and exchanged for empathy and political mobilization. However, this racism is not new, and this empathy is tinged by an ephemeral character that we’ve witnessed and have felt before.

XiXi Yang (journalist and founding member of the Asian Women Alliance): I credit much of the mainstream coverage of AAPI hate crimes to the fact that the new generation of Asian Americans is not afraid to “show receipts” on social media. The sad reality of the Asian American identity is that we’ve often been asked to “prove” racism. While previous generations have relied on authorities and federal institutions to recognize threat and enact policy changes, the new generation is taking it upon themselves to hold individuals and brands accountable to #StopAAPIHate. Social media is so instrumental in amplifying our voices and pressuring mainstream media, authorities, and federal institutions to show us through actions that they’re listening. By posting and sharing graphic videos and photos documenting anti-Asian hate crimes, we are dismantling the harmful “model minority” stereotype while educating others on what it’s like to be Asian American today.

There’s this idea that Asians are sometimes encouraged not to speak out or cause a fuss, for fear of bringing unwanted attention and shame on the family. Where do you think this stems from?

Mecija: My parents migrated to Canada from the Philippines with a reverence for their new host country. The move to Canada provided them with the opportunity to build a life outside of the poverty and political unrest they faced in the Philippines, and a feeling of indebtedness to the nation informed how my sisters and I were parented. My sisters and I were raised in a small, predominantly white city called Brantford. We were never taught Tagalog, the most widely spoken language in the Philippines, and we were discouraged from trying to mimic its sounds so that our learning of English would not be interrupted. My parents were fearful that if we spoke their language, we might acquire accents that were, to them, explicit markers of difference.

My parents understood success as being able to seamlessly assimilate into the expectations, etiquettes, and behaviors that were demanded of them by whiteness. They performed the expected comportments, or what scholar Robert Diaz might call the “ruse of respectability.” The desire to belong or deflect the trauma of racism conditioned my parents’ emphasis on fitting in or outdoing our white counterparts, but can you really blame them for wanting to protect their children from the pain of difference?

Reyes: The image of the brown person keeping their head down, being industrious and productive, and not making a fuss is the image of the good colonial subject. This is also the power of the myth called the “American Dream;” if we are not well-behaved, if we do not conform, then we will never succeed in their universities and corporations, and we will never gain acceptance in this country.

Lin Chen: I think structural racism has held us back from taking action — racist actions and words are meant to belittle us and make us feel afraid. So many people stay quiet because they think it’s the only way to stay safe. But our collective voice is growing, and I hope that people are listening.

Ashley Rachel Villa (lawyer, CEO and partner at Rare Global, and member of the Asian Women Alliance): We’ve always been taught that hard work will always get you through. Our parents valued work ethic and getting the job done, no complaints. So keeping your head down and doing the work was normal, because it supported the family and long-term stability. The older generation was happy to have that; that was enough — the opportunity to be alive in America. They wouldn’t think of demanding more. They saw mistreatment as yet another obstacle they’d overcome.

Bing Chen (president and co-founder of Gold Rush, an accelerator helping to create and empower more C-suite Asian leaders): Being “well-behaved” is certainly a shared experience among some whose parents came here, often with very little but themselves. While it may have made sense for the time, as history has consistently shown us through the Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese internment, and now record-high AAPI crimes, when you don’t speak up, you’re more than just erased — you’re attacked.

Yang: I grew up in a traditional Chinese immigrant family where I was taught to just blend in and not “rock the boat.” After years of not speaking up, I finally came to the realization that it hasn’t gotten better; I’m not on the boat anymore. I am just as American as anyone else and I belong here. This is my home. As a proud American, it is my responsibility to speak on my experiences to inspire others and hopefully pave the way for a better future.

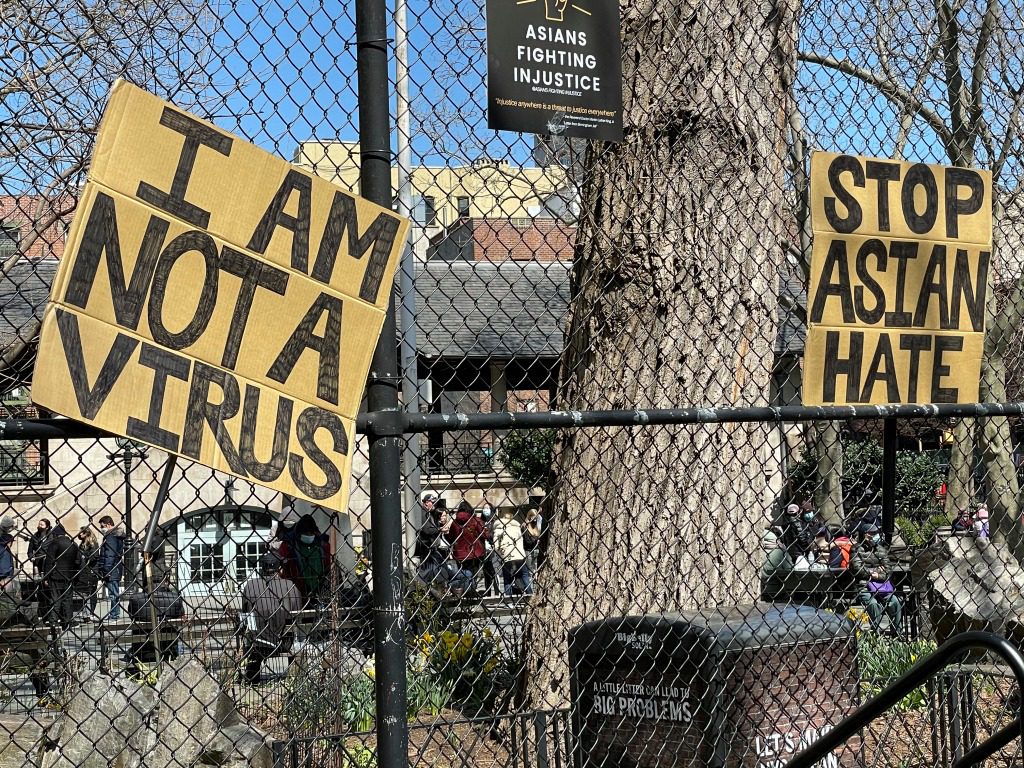

Rally to “Stop Asian Hate” at Columbus Park in New York

STRF/STAR MAX/IPx

Can you think of examples in your career where you felt like you had to hide your voice? Or maybe you had your voice silenced because you were Asian?

Yang: Throughout my career as an on-camera entertainment journalist, the biggest challenge I’ve had to overcome is not just finding success, but rather finding success without compromising who I am. The first red-carpet film premiere I got credentialed to cover, the head of the studio publicity firm put me in the “international press” section of the carpet, even though I explained to them I was working for a domestic U.S. outlet. The first hosting job I almost booked, the casting director told me that although I had “great energy” and “good delivery,” they weren’t exactly thinking Asian for the “ethnic/diverse female host” role. The first on-air guest-hosting gig I booked at a cable entertainment news network, someone made the suggestion to me that if I would change my name to something easier to pronounce, the executives would consider offering me a full-time employment contract.

Lin Chen: There have been several instances throughout my career where I’ve felt that others weren’t perceptive to my voice, or the voices of my Asian clients. I specifically remember helping a brand with formulas based in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and another brand that formulated with traditional Mongolian ingredients. Both brands had major pushback from retailers, since they claimed that their customer base wouldn’t understand or appreciate those formulation perspectives. It was disheartening and exhausting to have retailers ignore the beautiful and unique perspectives that these brands had to offer.

As I launched the Pink Moon brand and web shop, I felt like I needed to silence my thoughts and feelings about Gua Sha. The inaugural launch to the Pink Moon line was the Rose Quartz Gua Sha Facial Tool. For me, that launch was a love letter to my heritage, but I felt like I couldn’t openly discuss it too much. I also felt like I couldn’t talk about the growing cultural appropriation of the Gua Sha practice or tool until recently.

Villa: As a woman in my early career, there were many moments where I had to keep my head down, do the work, and ignore harassment. Becoming an entrepreneur, building a women-run company, and co-founding a women’s nonprofit has been my way of embracing my voice, speaking out, and creating opportunities for women, with women. It’s given me the confidence in my life and work. And yet, like many Asian women I know, it’s not been easy to deal with recent events. There are so many feelings we are currently processing, like why is it so hard for us, Asian people and Asian women, to speak up for our own culture, when we are inspired to use our voice for other things? I think as a whole community we are reckoning with all the things we have internalized and repressed as a result of our Asian-ness. I think we are waking up now.

How has Asian trauma been minimized in society over the years? Why do you think that is?

Mecija: While incidents of rising hate crimes against Asian people can be written about, quantified and archived, the trauma associated with racism and racial difference is not so easily articulated. Scholars David Eng, Shinhee Han, and Anne Anlin Cheng have named the psychic, immaterial and deep-seated impacts of racial experience as “racial melancholia.” The term stems from psychoanalytic theories of mourning and melancholia first introduced by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

Mourning is something everyone encounters. You experience a loss; you mourn it and then get over it. For example, you might lose a grandparent, and after some time has passed you replace the feeling of grief with something else, and you move past it in some ways. Melancholia is trickier. Instead of loss being a part of someone’s world that they can eventually get over, when you are melancholic, the loss becomes the world itself. The loss swallows you and it becomes deeply a part of who you are. Melancholia is mourning without end.

I bring up racial melancholia because it captures the loss and isolation experienced by racialized people that is caused by an unattainable whiteness. Racial melancholia also turns our attention to how having a proximity to whiteness has levied the unrecognizability of Asian pain and injury. The stereotype that Asians are the model minority places us in a position where we hesitate to complain or question the institutions that have granted many Asians’ access to socioeconomic ascendence. Asians are often signified as immigrants who overcome adversity by working hard. The transgenerational inheritance of “being grateful” supersedes any holistic recognition of the trauma that may have been endured in the process of attempting to fit in.

Reyes: The fact that so many Asian Americans are trying to appeal to the humanity and goodwill of white dominance is telling. In white dominance, we were never human beings. Our nations have been invaded and pillaged, our elders, our families violated in American wars in Asia. That trauma has always been minimized as acts of violence portrayed as individual acts, rather than the deliberate campaigns to terrorize the people into submission.

What exactly does the idea of the model minority mean and how does it fit into what’s happening today?

Mecija: First widely promoted in The New York Times by William Peterson in 1966, the myth of the model minority obscures histories of anti-Asian racism. The term makes reference to minority groups that achieve high levels of socioeconomic capital and places them in opposition to other immigrant populations. In an article for The New York Times, titled “Success Story: Japanese-American Style,” Peterson emphasized that hard work helped Japanese Americans to overcome racism. The underlying logic of the myth of the model minority suggests that if Asians can be successful despite racism, then other racialized groups should be able to achieve the same success. Never mind centuries of institutional racism and a history of genocide and slavery that have differently denied black and indigenous people of resources. The model minority not only veils racist history, but it also negates any socioeconomic disparities within Asian communities; we’re not all the same.

How were you able to push back against some of the Asian stereotypes that may have been placed on you, both in your everyday life and career?

Bing Chen: As a third-culture kid who was often the only API in certain spaces he was in (which continues to this day), I was always forced to thrive as “the only one.” But over time, being unique became a weapon — not a deficiency. When my father died when I was 14, this was only cemented: You have one life, it is shorter than you think, so are you spending it like it’s yours or someone else’s? That experience — seeing the end for someone you love — is my thrust for everything. I have little patience for anything that’s not good-natured and impactful because I know what’s at stake; I know how much life we can give, but also how soon it can be taken.

Villa: I went to law school because my parents, like most immigrant Asian parents, didn’t believe in careers in marketing and communications — they dreamed of me having a nine-to-five job, with stability, working for your vacations. Those were the examples they had of making it in America. Once I got out of law school, the world was beginning to change, with digital media, new-age marketing, and entrepreneurship. All of a sudden, I saw women living lives with an amount of creativity, freedom, and control that I never thought possible. My first and longest-standing client, Jenn Im, is a YouTube pioneer who first showed me that Asian American women could carve out their own space in digital media, drive a new industry, and have a lasting career on their own terms. So, I strongly believe that examples are what inspire — that led me to take a leap of faith to build my company and strengthen my voice.

Lin Chen: The impetus for starting Pink Moon was actually a breakup. I had just gotten out of a toxic relationship, and I was in the process of trying to rediscover myself and reclaim my life’s journey. Beauty rituals became a true source of self-care for me and actually helped me tremendously on my healing journey. Eventually, it became apparent that I needed to help others who were just as passionate about the power of beauty rituals. As I was dreaming of how to do this, I encountered some saddening realities about how little Asian women (and other women of color) are represented in the business side of the beauty industry. Truthfully, learning those facts only fueled my desire and made me dream bigger. I want Pink Moon to become a space of empowerment and representation.

Why is it important for Asians to speak up for themselves, and speak out against the racist rhetoric that’s being perpetuated right now?

Reyes: If we are still holding on to that model-minority image, going to great lengths to demonstrate our American loyalty and hoping for their acceptance, we need to let that go. If we are choosing to sit in darkness, disconnected from our own histories of resistance, we need to do better than this. I am an educator, and I cannot emphasize enough that we take our education into our own hands as individuals and collectives, unlearn the colonial histories we’ve been fed, in which America has presented itself as benevolent and heroic, and which we’ve come to accept as the only truth. Let that self-knowledge determine our actions, in service of our people, for the well-being of our people.

“If we are still holding onto that model-minority image … we need to let that go.”

Yang: Asian Americans have stayed silent in the past due to fear, and things have not improved. We can’t afford to stay silent anymore. We must find the courage within to speak up and hold individuals and companies accountable. The hashtag #StopAsianHate is a movement, not just a moment. In order for progress, we have to take this moment to truly encourage members outside of our communities to learn about the Asian American history.

Bing Chen: The beauty of starting your own company is you are the ceiling you set. That’s not to say there aren’t persistent biases (women of color still account for fewer dollars of venture capital raised due to systemic access issues, misogyny, and other biases). But it is to say that starting your own house is one way to accelerate economic growth rather than trying to take someone else’s. If you ask many API founders, they actually identify their race as one dimension that can contribute positively to their company’s outcomes because of their unique lens on traditional issues.

New Yorkers United against Anti-Asian Violence and White Supremacy meet outside City Hall in New York.

STRF/STAR MAX/IPx

What are some concrete steps we can take to help stop AAPI hate?

Lin Chen: Truthfully, I’m still in the process of learning how I can do better for myself and my community. It’s truly a process, but I do think that having conversations is the best place to start, whether those conversations take place with your family, your friends, or a larger public audience.

Villa: I think hearing lived stories about experiences with racism from Asian leaders in the media has been moving and eye-opening to the whole community. More people coming forward has helped others feel less ashamed and alone. I hope we can work together to destigmatize talking about these experiences so that we can support each other and empower each other.

Bing Chen: Punitive safety measures are only one-half of the battle — the more pernicious and foundational issue that causes this racism is socioeconomic inequity. We need to invest in and promote more authentic, prominent portrayals of our community worldwide and invest (financially) in our ability to invest in our communities, whether that be investing in small businesses or patronizing existing ones. When a people are seen the way they want to be seen and occupy influential spaces where they can make decisions that benefit all, they’re able to more easily control their community’s safety and societal progression.

Related: What You Can Do About Anti-Asian Violence

What do you want non-Asian friends and allies to know?

Mecija: I think it’s a time to collectively examine and work through racial grief rather than jump to resolutions, policies, and slogans that skip the important process of recognizing the emotional injury caused by white supremacy. I’m not suggesting that these types of responses are counterproductive, rather, I think there’s a melancholic substance that needs careful attention and care. I certainly feel that within myself. There is a deep, cutting sadness and anger that occurs when a white police officer excuses a white terrorist for killing six Asian women because he had a “bad day.” I’m on a group text with other Asian women and we have created a space for shared anger and sadness in all its fullness and without hesitation. This small, collective gesture has provided much-needed relief and support. It’s not so much a question around what we deserve but an insistence that this is not a moment to wage competing grievances or calculate who is the most injured or who is in the most pain. This is instead a moment to recognize that there is pain that is deserving of care. My hope is that we can build meaningful coalitions that work across difference towards an ethic of care and accountability.

Yang: Now is the time for our non-Asian friends and colleagues to show us through their actions that they’re listening. As opposed to denying racism or telling us how to feel, there is so much power in listening to an entire community’s hurt.

“My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.”

What is your hope for the Asian community moving forward?

Lin Chen: I hope that we continue to walk in solidarity with one another. We need to keep advocating for ourselves, uplifting one another, and working to dispel the model-minority myth.

Bing Chen: It can be scary for some people to speak up (as my own mother still worries I’m putting my life in jeopardy), but the other side of speaking up isn’t always danger — it can be a better life. Moreover, this model-minority myth-laden behavior still implicitly pits minorities against each other, and when that happens, only incumbents win.

Reyes: I would encourage folks to be emboldened by your fellow Asian Americans who speak publicly and with authority for our own communities’ perspectives, needs, and demands. I would encourage members of the Asian American community to learn about our American histories of resistance, of solidarity-building with other BIPOC, of which the arts has always been a vital part.

I started out as a young, shy, aspiring writer with private notebooks of poetry I was afraid to show anybody. Of course, there is therapeutic value to this, using the page for catharsis. It wasn’t until I found mentors and teachers that I learned what power our communities have always had, that it became easier to speak. Audre Lorde wrote in her essay “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action”: “My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you.”