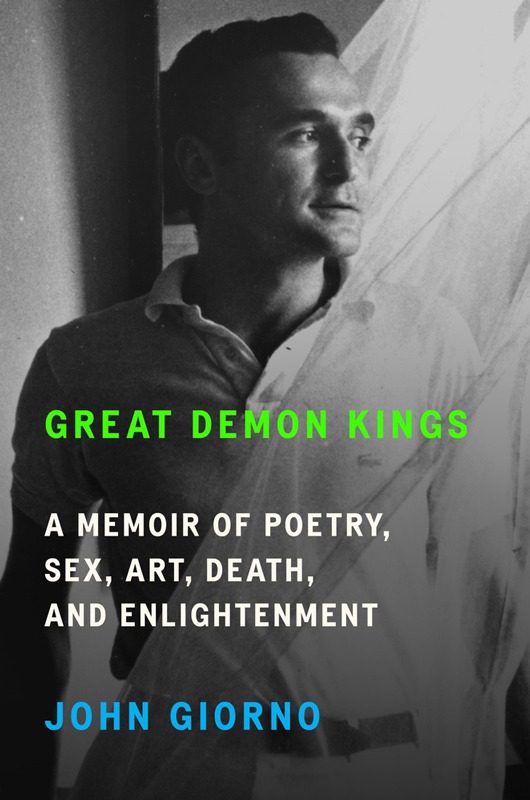

By now, it seems as if we’ve read, seen, and heard about every reaction possible to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, since it’s been the fodder for countless stories meant to explain to later generations why it was a pivotal point in history. But nothing quite prepared me for a tender moment between Andy Warhol and poet John Giorno 80 pages into his memoir, Great Demon Kings, on that day in 1963.

“Andy and I grabbed each other, hugged and hugged, pressing our bodies together, trembling. We both started crying, weeping big fat tears. We pressed our faces together and kissed. It was the first time we had ever properly kissed, sober and intentional. It had the sweet taste of kissing death. It was exhilarating, like when you get kicked in the head and see stars.”

This sweet side of Warhol, typically portrayed as the enigmatic weirdo with the bad wigs and monosyllabic catchphrases, is one that we’ve rarely seen portrayed. This scene comes after earlier descriptions of oral sex and hand jobs between the two, and after Warhol records Giorno sleeping for weeks so that he could premiere his nearly six-hour-long art film Sleep. It’s a few pages before they end up at a kooky meeting with Salvador Dali and his wife, Gala, at the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis hotel in Manhattan. And that’s followed by more gallery openings, party hopping, paintings — and more sex and poppers. Giorno — who up until this point is a Wall Street drone with poetic aspirations — is obviously giddy with all this bon vivant FOMO fun, until their friendship ends with a whimper, primarily because Warhol failed to invite his sidekick (whom he perpetually introduces as “a young poet” to all the movers and shakers they bump into) to a big party to honor old-guard poet John Asbury.

It’s these effervescent moments that make Giorno’s book such essential, joyous reading as we follow his adventures meeting soon-to-be-famous artists, dancers, musicians, and writers of Sixties New York. He spent 25 years writing the book, and thankfully completed it just a week before he died last year at the age of 82. Although he may be mostly forgotten by younger generations, Giorno’s influence on poetry, art, and performance culture continues to be great. Now, thanks to his diligence in documenting so many personal details — and floridly annotating so many behind-the-scenes affairs — he has a chance to be reconsidered and credited with being one of the great gay sex-positive pioneers of the late 20th century.

The most marvelous thing about Great Demon Kings is that Giorno doesn’t shy away from writing about sex. In quick succession, he’s not only the erstwhile lover of Warhol, but soon he jumps from artist Brion Gysin to painters Robert Rauschenberg to Jasper Johns. He still has time to take his intense bond with an aging William S. Burroughs — the “sacred demon” with whom he feels a deep “karmic connection” — to a new realm when they get naked and eventually screw, which is described with such lucid vulgarity that it may make you reconsider the power of sex for perpetuity. Giorno is well aware that these artists have been mostly neutered by their legendary statuses, and he’s helpful in explaining why his entitled, bourgeois background allowed him more freedom to feel liberated from societal restrictions of the period.

“I was annoyed by all the gay artists … who never allowed themselves to use gay images in their art, because they did not want to ruin their careers or compromise their ability to make money in a homophobic world. But I also understood. They mostly came from poor families, and I was from the upper-middle class, which gave me the privilege to do what I wanted. And poets have nothing to lose anyway.”

Giorno’s “heroic aspiration” was to take homoeroticism “to another level” in his work. He employs pornographic imagery in his poetry, reveling in the subversive nature of guerrilla publishing just as the Supreme Court ruled Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer was not obscene. He also collaborates with Bob Moog, using his early synthesizer invention to create sound compositions just as it begins to revolutionize rock & roll. But Giorno’s biggest feat was his Dial-a-Poem, launched in 1968, which allowed people to call a phone number and hear a different prerecorded poet reading for two minutes (John Cage read from Silence, Frank O’Hara from Lunch Poems, Jim Carroll from The Basketball Diaries, etc.). He credits it with ushering in a “new era of telecommunications, bringing poetry to millions of people,” until it was eventually made obsolete by the internet.

Reading the breezy, delicious accounts of so many art world and literary luminaries certainly focuses attention on them in a refreshing way. And despite all of Giorno’s own creative accomplishments, one can feel his frustration at never getting his time to shine fully. At one point, he admits that for all his noble attempts at connecting, he could be “just a shameless hustler.” Later, he admits his frustration that Anne Waldman published a poem about a summer visit with Jasper Johns in Nags Head to which Giorno invited her, and there’s no mention of him: “I was a bit shocked. It felt all too familiar: As I had been with Andy, and then Bob, I was being edited out of my lovers’ stories.”

Giorno eventually finds his second act in life after he journeys to India and studies Buddhism at the urging of his former hero, now “nemesis,” Allen Ginsberg. Although his crisis of consciousness finally seems under control, Giorno continues to be baffled by life’s inequities, giving a very moving account of his testicular cancer, stating: “Wisdom arose in life as metaphors, and having my ball cut off symbolized the complete failure of everything I believed, hoped, and aspired to.”

Dreamers have been coming, and hopefully will continue to come, to New York looking for a romantic notion of an artist’s life. In some ways, Great Demon Kings feels like a counterbalance to Patti Smith’s Just Kids, which touches on similar themes for a later generation also pulled into this orbit of creative genius. Smith did an excellent job of myth building in her book, excising anything that could be construed to make her look obviously ambitious or silly, pretentious or intolerant, whereas Giorno wallows in all the messy details: the gossip, the jealousies, the star-fuckery, and the blatant grandiosity. The fact that it won’t receive the same type of rabid and critical accolades as Just Kids is a shame. Part of that is because poets who don’t put music to their words aren’t often celebrated as widely — especially when they’re pushing boundaries of pornography, sexuality, and have little time for elegiac prose or “good taste.” The other reason why Demon Kings won’t get as many kudos is due to the writing itself; Giorno often goes for blunt details wrapped in cosmic language that’s not the type of thing that is easily applauded by snooty awards boards and literary aficionados (I’ll never forget the threesome between him and William Burroughs and Ginsberg for its quotidian imagery that ends with the oddly pompous addition that they were all “very respectful of the sacred quality of the moment.”)

Hopefully the book will connect with readers, those hungry to see that queer, sex-positive energy thrived long before the Stonewall uprising made 1969 a milestone for LGBTQ liberation and that one of the ways to battle for love and sexual freedom is to dedicate one’s life, and work, and whole existence in a celebratory pursuit of those very things.