Inside the Race to End the Pandemic

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine put their lives on hold to create a Covid-19 vaccine — and with the weight of the world on their shoulders, there's no end in sight

This spring, doing rounds in the Covid-19 units at the University of Maryland School of Medicine hospital in Baltimore, Dr. Kirsten Lyke saw more than 130 patients each day. Some were under observation after developing symptoms like shortness of breath, dry cough, and fever. Others were on ventilators. Many initially tested negative for the virus, only to have a more precise follow-up test indicate that they did, in fact, have Covid-19.

Sometimes, it happened fast. Newly diagnosed Covid patients — who required only a few liters of oxygen when they were admitted — could end up on life support by the following morning. People who only a few months prior would have been considered too young to have their lives seriously threatened by a virus filled the beds. To protect her young son from exposure to the novel coronavirus, Lyke moved him in with a close friend of hers in Philadelphia.

By mid-May, much of the hospital had been converted into Covid wards, including three now operating as Covid ICUs. In those wards, an iPad was positioned beside each bed, with its camera and two-way speakers switched on around the clock. Down the hall, doctors and nurses hovered over monitors in a room converted into the pandemic version of Mission Control. Though many patients were on ventilators and unable to communicate, this setup allowed the medical staff to keep an eye on them, minimizing contact.

Dressed in personal protective equipment from head-to-toe, Lyke and her colleagues would enter the ward to the chorus of overlapping beeps coming from the ventilators and monitoring equipment — an aural reminder of the urgency of their work. Being part of a team whose members risked their lives to care for other people resulted in a formidable bond, Lyke tells Rolling Stone. “It really felt like we were in a war together.”

But the hospital wasn’t the only battleground. About 100 feet away, across a tree-lined street on the medical campus, was UMSOM’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health. There, Lyke was the co-principal investigator on the first phase of the Pfizer Covid vaccine trial. Doing both jobs meant long days for the physician — she started at 6 a.m., four hours before her hospital shift began, and went well into the night. By mid-May, as Maryland hit more than 1,000 new cases daily, the research was also at its peak, and Lyke spent her days dashing between the hospital and the research laboratory. Everything was happening in real-time: treating people hospitalized for Covid, while simultaneously trying to create a vaccine. “I don’t think there has ever been an experience like this in modern medical science,” Lyke says. “We’ve done other trials where we have a sense of urgency, but this one is off the charts.” To track this historic progress, Rolling Stone conducted months-long interviews with the doctors and scientists at the forefront of this research to see how, as the death-toll rises, a potentially world-saving vaccine is coming together.

Instead of bags filled with fluids and liquid medications, in the halls of the Center for Vaccine Development, blue surgical gowns hang from IV poles, alongside cardboard boxes full of supplies. At first glance, it could be any hospital from the early Twenty-First century: clean and minimal, with white and gray walls and just enough light-oak finishings to give it a little warmth. But within seconds of entering the building, it’s clear that this isn’t a typical medical facility. The energy is different. Instead of patients fighting for their lives, volunteers eagerly roll up their sleeves as they take to the high-backed, padded sea-foam green chairs, to make the process smoother for the nurses administering their experimental vaccine candidates.

Overall, developing a vaccine for Covid has been very different from any inoculation that came before it. First, there’s the speed: The initial cases of non-travel-related Covid in the United States were confirmed at the end of February; Less than a month later, Pfizer announced that it had partnered with German biotech company BioNTech to develop a Covid-19 vaccine. They were banking on the combination of BioNTech’s expertise in mRNA vaccines with Pfizer’s manufacturing capabilities and familiarity with the American regulatory processes to get them to the finish line as quickly and safely as possible. On May 4th, 2020, the team at UMSOM vaccinated their first volunteer, kicking off the phase-one clinical trials in the United States. Trials at the three other sites — New York University, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, and the University of Rochester — soon followed.

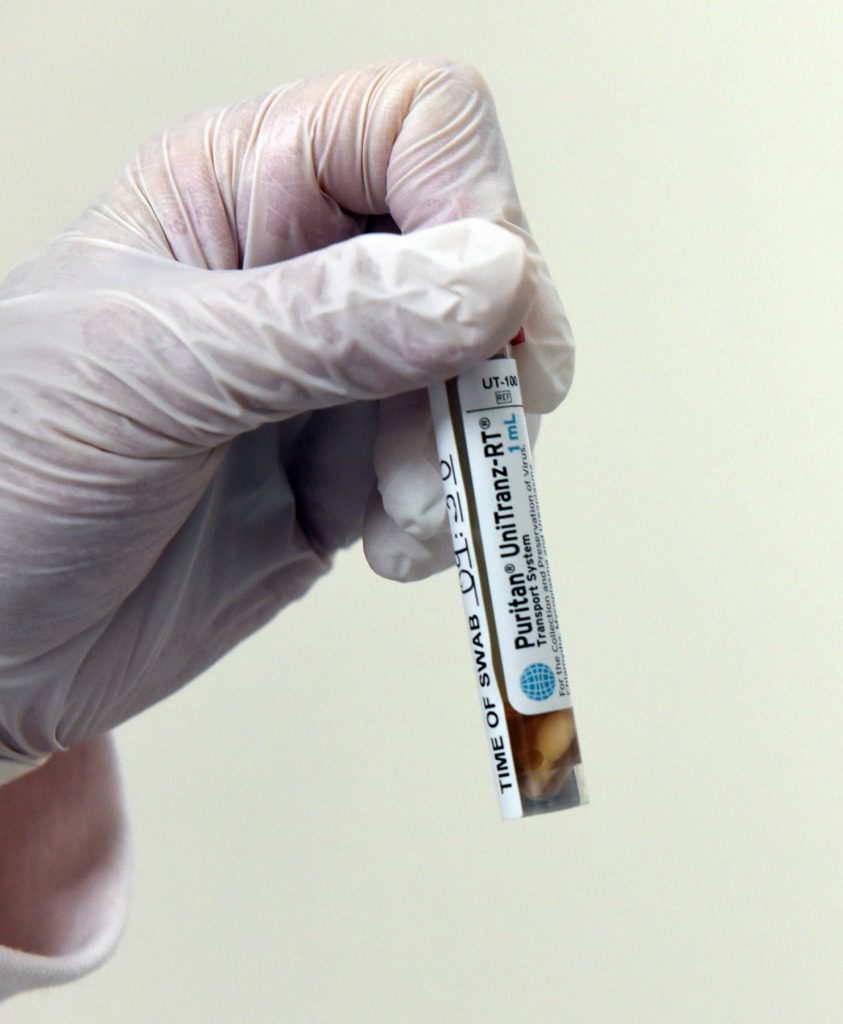

A vial of one vaccine being tested in the Pfizer trial at the University Of Maryland School of Medicine.

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Unlike many vaccines — which can contain the entire virus, whether live, dead or alive in a weakened form — the messenger (m) RNA is essentially a piece of genetic code that instructs cells to make a protein. In this case, it’s portions of the coronavirus spike protein. “We’re basically tricking our bodies into thinking that it’s seeing the virus, and to produce antibodies to fight Covid-19, when all it’s really seeing is the spike protein,” Lyke explains. “The protein acts like a ‘red flag’, which our bodies attack in the form of an immune response, and which we hope will provide protection against the coronavirus.”

Typically, a phase-one trial would have between 40 and 60 participants, and take between 12 and 18 months to get FDA approval and for testing to get off the ground. This one involved enrolling approximately 250 volunteers across four sites and many different arms, and came together in three weeks. Instead of taking several months to review the trial, the FDA took eight days. “Every step along the way, it’s just been 24/7,” says Lyke, who is also a professor of medicine at UMSOM. “We still have the same safety milestones, [and] we’re still monitoring the volunteers very carefully.”

The interdisciplinary center at the CVD — comprised of 35 faculty members and 120 nurses, lab techs, pharmacists, and other staff — employs some of the most experienced vaccine researchers in the country. There’s Lyke, whose background in malaria and tropical diseases — as well as her experience treating Covid patients — means that she knows what the virus looks like on the ground. There’s Dr. Wilbur Chen, an experienced cholera researcher and advisor to the governor who is responsible for communicating the scientific aspects of Covid and the vaccine trial to the general public. There’s Lisa Chrisley, the trial’s clinical research manager, who supervises a staff of 20 to ensure that even the minute details of the operation are in order. Each person has spent their career honing the specialized skills and knowledge that would eventually put them in the position to lead groundbreaking vaccine research around the world. “Pretty much every step along the way, everyone just dropped everything and immediately launched into their portion of getting this moving forward,” Lyke says. After working to develop life-saving vaccines in other countries, the members selected for this team joined forces to face a threat to global health that hit close to home.

Along with the research staff, the volunteers also played an integral role in the story of the vaccine trial. Ranging in age from 22 to 83, the 87 volunteers at the CVD included everyone from college students to construction workers to a national pickleball champion. “In general, there was a real spirit of altruism,” Lyke says, adding that many of the participants asked if they could donate their volunteer compensation. “All were grateful and excited to participate.”

Every week of the trial, the participants received escalating doses of the vaccine, which were randomized and blinded — meaning that neither the participants nor researchers know which iteration of the potential vaccine they’re getting. To make things more complicated, the trial wasn’t testing a single vaccine: initially there were four permutations administered in three different doses, meaning there were a total of 12 distinct combinations. The permutation that had the most promising results and was the best tolerated across age groups has moved on to its final phase, where it is currently being tested in 44,000 people nationwide.

When testing a vaccine to respond to a virus that has only been around for a few months, there’s no existing formula for the vaccine itself, or for the operational needs of the clinical trial. Even under the most straightforward circumstances, vaccine research is logistically complex, requiring team members to take on multiple responsibilities, all while navigating federal regulations and each study’s individual design.

Everything has to be made from scratch, from the case-report forms, to the electronic databases, to the training seminars for those working in the lab and with the resulting data. And though this all had to be done relatively quickly, the team understood that the Pfizer phase-one trial would likely be the first of many, and developed forms and other procedures that could be used for future Covid research. For example, back in May, before the trial was up and running, Lyke created a general protocol for recruiting volunteers for any type of Covid-19-related studies, including vaccine trials, plasma research, and serologic studies. “It gave us a template to start to look at the Covid vaccine effort in an overarching way — not just for Pfizer, but for future studies,” Lyke says.

With countless moving pieces — along with the new issues that crop up as a trial progresses — it’s crucial to have someone overseeing the entire operation. In this case, it’s Lisa Chrisley, a 20-year veteran of the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health. Her colleagues refer to her as the “backbone” of the study, in awe of her ability to keep the operation not only running smoothly and safely, but doing so at unprecedented speed. In addition to being a registered nurse, Chrisley’s position as the clinical research manager for the Pfizer vaccine trial made her responsible for supervising the approximately 20 staff members working on various aspects of the research — from interacting with the participants, to trainings, to making sure there are supplies, to liaising between the lab, pharmacy, and regulatory staff. And while the research deals with a novel virus, Chrisley is confident in the ability of the team. “Since 9/11, we’ve been on the frontline of public health. We’ve been through smallpox, anthrax, bird flu, Ebola, Zika, H1N1,” she says. “This is what we do.”

Following medical school, doctors complete a notoriously stressful one-year internship. It involves working long hours, dealing with intense pressure, and spending every second or third night at the hospital. But what makes it bearable is knowing there is a set end point, says Dr. Kathleen Neuzil, the director of the CVD, who frequently uses this analogy as a way to illustrate the specific stress that comes with performing this type of exhausting and demanding work with no certainty as to when it will end. “There’s a lot that makes the Covid vaccine trial unique, including that we’re really moving with unparalleled speed,” says Neuzil, who, along with Lyke, is a co-principal investigator of the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine trial.

David Rach, a graduate student at the University of Maryland, was the first to be vaccinated in the Pfizer vaccine study.

University of Maryland School of Medicine

An expert in both the science and policy of vaccine research — she’s served on committees for both the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control — Neuzil’s background in advocacy complements Lyke’s clinical and research experience, making them a formidable pair to battle the vaccine’s distinctive challenges. These include everything from operating at a significantly faster pace without compromising safety, to concerns over team members’ own health. “We have learned risk mitigation. We’ve learned to be smart. We’ve learned to work in teams, because you’re never quite sure what’s going to happen, who might get sick or pulled away,” Neuzil says.

Since the beginning of March, Neuzil has worked seven days a week — in the hospital for 10 or 11 hours, then catching up on work after dinner. “I am the director, and I like to be here if I’m requiring staff to be here,” she says. Her days begin at 5 a.m., and can involve 6:30 a.m. dial-ins for calls with teams working on vaccination development in Africa or Europe, for which she serves as a strategic advisor. After that, Neuzil spends most mornings working on and overseeing the multiple studies taking place at the CVD, including the Covid-19 vaccine trials. Beyond the CVD, she is also consulting on the organization of a multitude of clinical trials taking place throughout the United States, as well as serving on a number of national advisory committees.

Yet despite her global scope, Neuzil says that some of the stress of the job comes from the fact that the vaccine team has collectively lost four relatives to the virus. “It’s very personal to all of us,” she says. “And you know you have some ability to change the trajectory. But you can’t pretend that you have control over it. And the uncertainty is so large: How long is this going to last? How is this virus going to surprise us today?”

Meanwhile, Lyke’s combined responsibilities have given her a rare perspective on the pandemic. “Seeing both sides of the equation — both treating patients directly and then going into the lab and trying to figure out the vaccine — they’re both so necessary,” she explains. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime scenario. Even when I’m rounding with my team in the hospital, we just stop and we’re like, ‘This is surreal. I can’t believe we’re doing this.’”

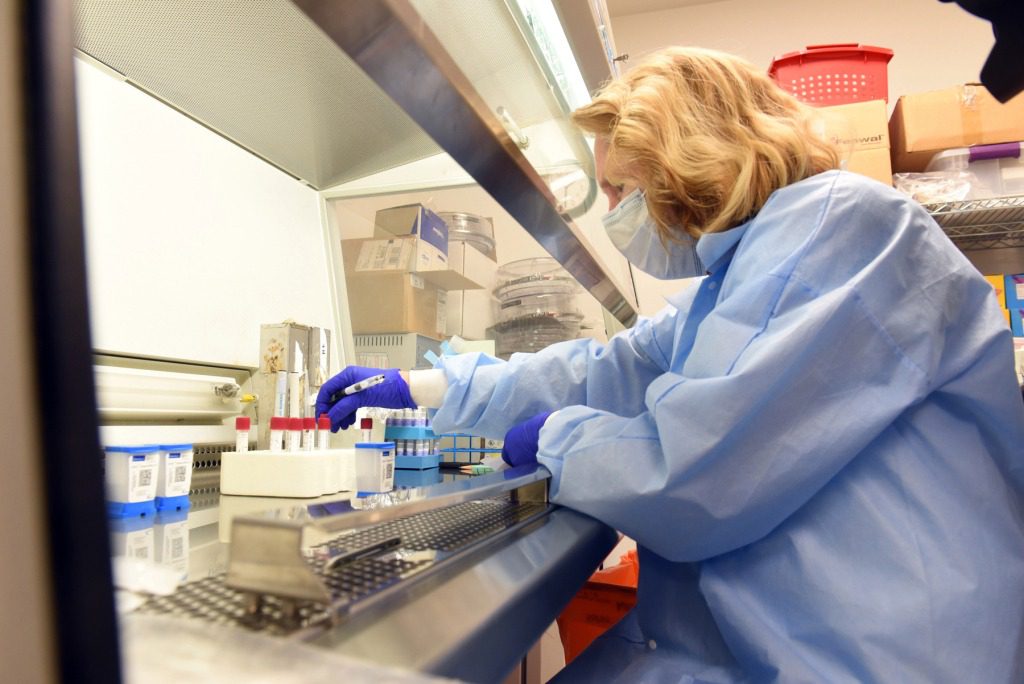

Kathy Strauss, a laboratory specialist on the team, says that while she feels the pressure of this particular trial, there’s nothing else she’d rather be working on. “If [Lyke] hadn’t asked me to do this, I would have been just devastated — crushed,” she tells Rolling Stone. Her role in the Covid vaccine trial involves utilizing a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method — previously developed with colleagues while working on a malaria vaccine — to determine whether subjects have the disease. In the Covid trial, blood drawn from a participant is smeared on a slide and examined under a powerful microscope to determine whether the person has developed immune cells. The blood smears are used both as part of the screening process to ensure that volunteers are healthy enough to participate, as well as during the trial, to monitor any changes in their blood.

Antibody tests to determine COVID status can’t always detect whether someone has the virus, but the highly sensitive PCR method uses the RNA of the virus to determine whether the participant is Covid-19 positive before receiving the vaccine. “This [trial] is similar to our malaria vaccine studies, but a lot more intense for obvious reasons, because with malaria, if we catch it, we can treat it,” Strauss explains. “The threat of death isn’t hanging over you like it is here.”

For Strauss, the stress and excitement of being part of this historic vaccine trial has manifested in the form of excess energy. “I mean, you cannot make a mistake during these [trials],” she says. “My biggest problem has been calming down.”

As the public face of the UMSOM vaccine trial, Dr. Wilbur Chen received an onslaught of angry emails and phone calls during the first several weeks of the study — primarily from people who were upset about how long businesses had been shut down. Serving as a liaison between the research team and those on the policy side of things, Chen has been in regular communication with the Maryland Department of Health, and serves on Governor Larry Hogan’s Covid-19 Task Force. Prior to Covid, Chen’s role as the chief of the adult clinical studies section at the CVD primarily involved conducting vaccine research — including serving as the principal investigator of the 2009 influenza national vaccine trials, and participating in research on Ebola and Zika.

Once Covid hit and Pfizer’s phase-one clinical trials began, Chen’s responsibilities shifted, and he spent most of his days outside the lab, taking calls and attending meetings. “I basically lend out my expertise to multiple groups to try to be the voice of reason, communicating the scientific basis for decisions made during this Covid-19 pandemic,” Chen tells Rolling Stone. “We would tell people that this is unprecedented — this is historic — but they didn’t always get it. It was frustrating on a daily basis, because we were trying to protect people — not trying to take away liberties.” Fortunately, once Maryland began to reopen, Chen says that the angry messages became few and far between.

Other members of the vaccine development team have also dealt with people with a wide range of perspectives: from those who think this is all a hoax and that vaccines are harmful, to those who believe in science but don’t necessarily understand the complexities of vaccine development. Chrisley, for one, understands that people are frustrated, and says this adds to the pressure she feels working on this trial. “I don’t know when we’re going to have a vaccine,” she told Rolling Stone in May. “I know we’re working as quickly as we can, but also ensuring that we maintain the safety of our participants and that we’re doing good science. And a vaccine will be ready absolutely as soon as we can do it in that manner.”

On one hand, Lyke says that it’s interesting to see people relying on science to come up with the solution to the pandemic. “But at the same time, you also see this fringe element, who are rearing up against the science and trying to say, ‘Well, you know, this is all fake,’ or, ‘You know, the numbers aren’t as bad as you’re making it out to be, and we should open up society and get on with it,’” she says.

Lab specialist Kathy Strauss conducts PCR testing as part of the Pfizer mRNA Covid-19 vaccine study. To decompress from her work, she makes monographs inspired by Covid-19 and other viruses.

University of Maryland School of Medicine

While there is some historical precedent for politicizing aspects of pandemics, John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza, says that the current situation is much different than the climate during the 1918 flu pandemic. First, the 1918 flu was much deadlier, so “nobody thought it was a hoax at any time,” he tells Rolling Stone. Also, the political impact of the 1918 pandemic tended to be localized, and not partisan. “Most cities had closing orders,” Barry says. “There was some pushback from the business community, primarily from bars, which were major players in a lot of political machines.” But unlike today, this type of political impact was on an insider-level, not a widespread disbelief in science split along party lines.

Lyke doesn’t waste her energy on partisan conspiracy theories. “Everyone on earth is equally susceptible to this virus, and if we don’t act together, it doesn’t really matter what state is opening up and which are remaining closed,” she says.

But it’s not only political: some people may be skeptical of the seriousness of Covid-19 and the recommended public health measures because information on the virus has been constantly evolving since January. “In public health, we usually like to be consistent [in our messaging]. But in this instance, we can’t,” Neuzil told Rolling Stone in May. “We don’t know enough about this virus, and so it’s better to be right than to be consistent. I understand that the public has heard different messages, so I think there’s been some expected pushback.” Still, after working nonstop for weeks or months on end, leaving the hospital and seeing people dismissing public health guidelines can feel personal. “It is a little disheartening when I go home, and I see so many people walking around without a face mask and not social distancing,” Lyke says. “It feels like the world thinks that this is ending. But it’s not.”

Over the course of the nearly five months since the Pfizer phase-one Covid vaccine trials began at the CVD, the team has had to adapt to constant updates to the trial — based on data emerging from the other sites — as well as keeping up with their ongoing research aiming to find effective treatments, including one trial involving the antiviral drug Remdesivir. The process has meant that people like Chrisley — who, in addition to the Pfizer vaccine trial, also oversaw two of the treatment studies — have witnessed the sheer magnitude of the pandemic. “We’ve seen firsthand how this virus ravages the body, and it doesn’t care about gender or age, or even if you have other health problems,” she says. “I mean, this virus is no joke.”

Though the team will be following up with the volunteers over the next two years, they gave their final doses for the Pfizer phase-one Covid vaccine trial in July. Based on the findings from the CVD and other testing sites, one of the vaccine candidates (BNT162b2 at 30 micrograms) was selected to move forward to the final stage of clinical trials. “We found it to be well tolerated, with near equivalent immune response in the elderly,” says Lyke, who, along with her colleagues, published their findings in the journal Nature in August.

Pfizer’s final phase of clinical trials began in July and includes approximately 120 clinical investigational sites around the world — but UMSOM is not one of them. Instead, Lyke, Neuzil, and their team are now conducting the phase-three trials for a Covid-19 vaccine candidate developed by Moderna — the first to be implemented under Operation Warp Speed, a multi-agency collaboration meant to accelerate the development, manufacturing and distribution of a Covid-19 vaccine. As a Vaccine Testing and Evaluation Unit for the NIH, the CVD is obligated to participate in phase-three trials for an NIH-funded vaccine, Lyke says, and Moderna got to that point first. But again, she emphasizes that the goal of the Pfizer and Moderna trials — as well as the others in progress around the world — is to find a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine to help slow the pandemic and save lives. “I would definitely term it as a ‘race against the virus’ and, in no way, a race against any other vaccine strategies or teams,” she explains. “I think all of us hope that many, many vaccine development teams are successful given the complexities of manufacturing and the sheer numbers of doses required.”

With both Pfizer and Moderna in the final stages of their respective Covid-19 vaccine trials, the focus now is on timing, in terms of if or when a vaccine candidate receives FDA approval, but more importantly, on a feasible timeline for manufacturing and distributing the vaccine to the public. When the Pfizer phase-one trial began in May, Chen thought that the absolute soonest there would be a licensed and available Covid-19 vaccine would be in 12 to 18 months. Now, he thinks that we could have clear efficacy data on the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine candidates by the fall or early winter. If that scenario plays out, Chen predicts that both companies will file their applications for licensure with the FDA shortly thereafter. Then, he says, it would take the FDA a few months to quickly review the applications and make a determination.

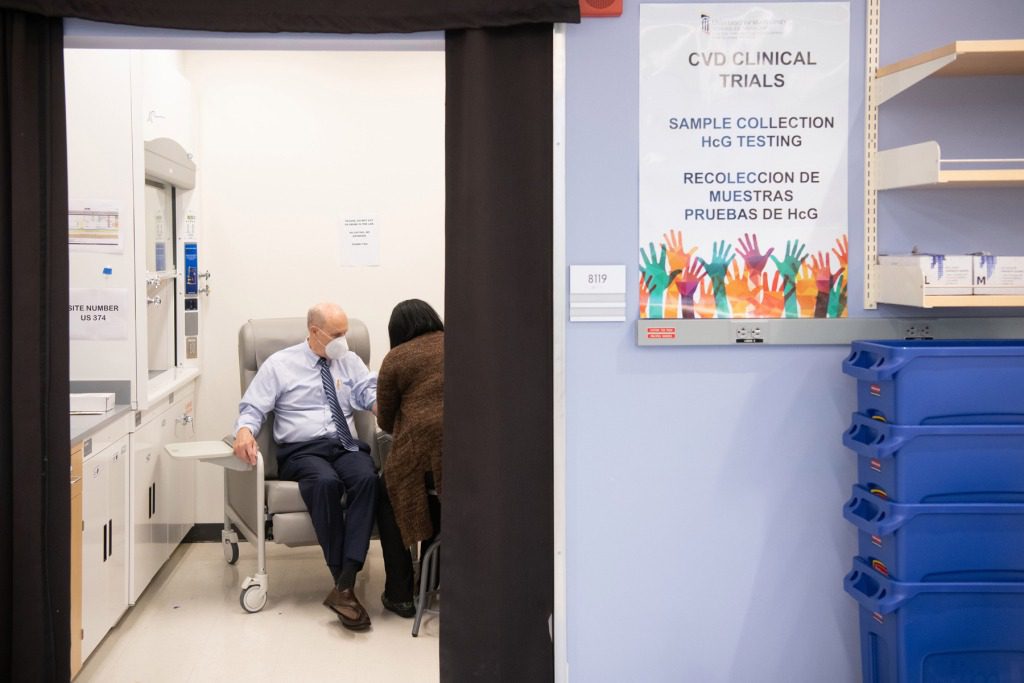

University of Maryland Baltimore President Dr. Bruce Jarrell participating in the Moderna mRNA Vaccine Trial.

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Meanwhile, Donald Trump has spent the past few weeks accusing the FDA of intentionally slowing down the approval process for Covid-19 treatments and vaccines, and has doubled-down on his claims that a Covid-19 vaccine could be ready by Election Day. The discussion even made it to the stage at the first presidential debate, when moderator Chris Wallace pressed Trump on his timeline, noting that CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield recently said that it would be summer 2021 before the vaccine was widely available. “Well, I’ve spoken to the companies and we can have it a lot sooner,” Trump responded on Tuesday night. “It’s a very political thing because people like this would rather make it political than save lives.”

Concerns over whether Trump may pressure the FDA into prematurely approving a Covid-19 vaccine mounted on September 2nd, when the CDC notified public health officials in all 50 states that they should be ready to distribute a vaccine by the end of October or early November. Chen believes that this was a partially political maneuver, though also points out that it will take a significant amount of preparation for states and territories to begin even limited distribution of a vaccine, so it’s not unreasonable for the CDC to request that they start the logistical planning now. When the FDA eventually does license a vaccine, there will need to be a “gradual ‘roll-out,’” he explains, noting that it will take time to produce 300 million doses of the vaccine. “The limited number of initial doses would be administered to prioritized populations.” However, Chen does not think it is realistic that there will be a fully licensed Covid-19 vaccine by November 3rd, 2020 — though he is optimistic about having one by November 3rd, 2021.

Since everything started, Strauss, a laboratory specialist in the trial, hasn’t slept more than three or four hours a night. Her 10-minute commute doesn’t give her much of a chance to decompress, and by the time she gets home, she’s still buzzing with excess energy from her day at work. She changes clothes, then takes her rescue Australian blue heeler cattle dog for a two-mile walk. Once she returns to her home in a small town just outside Baltimore, she heads to the room that prompted her to purchase this particular house: her art studio.

Flooded with natural light from three large windows, Strauss’s workbench is covered in paper, rulers, and supplies for painting and embroidery. She is currently working on a monotype, which involves painting on glass with printing ink and then transferring the image onto paper. “You have to do it really carefully,” she tells Rolling Stone. “That’s what a monotype is — you get one print.”

At the beginning of the trial, Strauss would come home and pace. But she soon realized that retreating to her studio was a more effective way to calm her racing thoughts. “When you’re at work, you’re so focused,” she says. “The stakes are so high for this because of what’s going on in the rest of the world.” To help deal with some of the stress, Strauss has been allowing herself three cigarettes each day, for the first time since college.

But her primary release has been making art. “All my work is about viruses right now, because that’s the only thing I can do to get rid of this,” she says. Her last three pieces are monotypes of the novel coronavirus, but even before the pandemic, she was working on a series she calls “Infectivity,” featuring other viruses, as well as bacteria. Much like her work in the lab, there is no room for error with monotypes: you have one shot at getting it right.