Gloria Cazares can’t tell you if she’s going to have a good day or a bad day. Some mornings, she wakes up, makes breakfast, and does a few chores around the house. Other mornings, she can’t get out of bed. The thought of cooking a meal is overwhelming. She scrolls her phone and bursts into tears if she comes across photos of Jackie, her nine-year-old daughter and one of 19 children and two teachers killed on May 24, 2022, when a gunman opened fire at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas.

Jackie was upbeat and enthusiastic, with long brown hair and big brown eyes. She had dreams of traveling the world one day — Paris was at the top of her list. Cazares still takes care of Jackie’s four dogs and talks about how much she wanted to be a veterinarian. There are memories that make her smile; some tear her apart. “I never know how I’m going to react,” Cazares says. “Sometimes, it’s remembering her smile, her laugh, her eyes, and it just breaks your heart. There’s so much that she’s going to miss out on.”

For the last year, Cazares has been caught in the unpredictability of grief. But there’s one thing that’s kept her moving: the fight to reduce gun violence across the country. She’s taken up the cause alongside many of the parents and loved ones of Uvalde victims and over the last few months, they’ve focused their efforts on HB 2744, a state bill which would raise the minimum age to purchase some semi-automatic rifles from 18 to 21 — something they believe would have prevented the tragedy in Uvalde, particularly because the gunman legally purchased two AR platform rifles just days after he turned 18. HB 2744 faces an uphill battle, but it’s just one of many efforts the families are working on as they seek change and demand accountability for what happened that day.

Gloria and Jacinto Cazares stand with their daughter Jazmin at a press conference in Washington, D.C., on July 27, 2022, months after losing their youngest child Jackie Cazares during the shooting in Uvalde, Texas.

Anna Rose Layden/Getty Images

They’ve channeled some of their energy into Lives Robbed, a nonprofit organization created by several parents of the victims, including Cazares. The idea came up in the months after the shooting, as the families began spending more time together at vigils and demonstrations, urging action from leaders in Texas. They became a constant presence at the Texas State Capitol in Austin, where they called out Governor Gregg Abbott and other Texas representatives. They also traveled to Washington, D.C. several times to testify before Congress and encourage the Senate to pass gun reform laws. It was during one of those trips that they began discussing Lives Robbed. “We thought, ‘Let’s try doing something. Let’s form something,’” Cazares remembers.

Organizations like Lives Robbed have come together in the aftermath of mass shootings before: After Sandy Hook, families and loved ones created Sandy Hook Promise and the Newtown Action Alliance, which both work to prevent gun violence and create safer schools across the country. Students joined forces to launch March for Our Lives, a youth-empowered non-profit, in the wake of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The Uvalde families had met with several people from organizations like these in other communities, and they wanted to find their own ways to make change. “We were always getting help from other organizations and we thought, ‘You know what? It’s time for us to get in there and start helping others,” Cazares says.

Lives Robbed includes the organization’s president Kimberly Mata-Rubio, a journalist who used to work at the local newspaper, the Uvalde Leader-News. She lost her 10-year-old daughter Lexi, a bright, ambitious kid who loved playing softball and basketball, and who always did well in school. “She was competitive, driven, definitely a bit of an overachiever,” Mata-Rubio says. “She would get nervous before tests. She really wanted to be great. She was great.”

Berlinda Arreola, the step-grandmother of 10-year-old victim Amerie Jo Garza, also became an outspoken member of the group, as well as its secretary. Garza was just six months old when she came into Arreola’s life, and Arreola always loved how artistic and creative she was. Garza loved to draw, and she was especially good at sculpting little objects out of clay. “She was so talented, and she was just so friendly,” Arreola says. “She trusted everybody.”

One of the mothers who joined Lives Robbed was a kindergarten teacher named Veronica Mata, whose youngest daughter Tess was among the victims. Mata had a hard time getting pregnant after she had her oldest daughter, Faith, and though Tess was almost 11 years younger than her sister, the girls were close. Tess loved sparkly dresses and makeup, but she was also a big baseball fan who cheered for the Houston Astros. “Tess was the light of our life. She kept us going,” Mata says. “She was spontaneous, and she was just very outspoken. When she didn’t like something, she was going to tell you that she didn’t like it. But she had the biggest heart.”

Mata says Faith, who took care of the family immediately after they lost Tess, wasn’t sure if she should go back to college at Texas State when the school year started. ” I knew that that was something that Tess wouldn’t want her to do,” Mata says. She thought Faith might be more willing to finish out her studies if she got back to work in the classroom. She’s one of the newer members of Lives Robbed member, joining as another way to keep Tess’s memory alive. “It’s all new to all of us,” she says.

Like Mata, none of the family members had a lot of experience with politics or lobbying efforts before the tragedy. Arreola says she hadn’t ever been involved in gun reform legislation or debates. “When Sandy Hook happened, I followed their story,” Arreola remembers. “But my biggest regret now is not following through with Sandy Hook and helping them with gun reform and school safety, because here we are 10 years later, asking for the same thing that they asked for.”

AS SOON AS LIVES ROBBED formed in October 2022, its members immediately began working. They attended meetings and urged updates from an investigation currently in process by the Texas Public Safety Commission. They rallied in Austin on Gun Safety Advocacy Day in February, standing alongside other families that have faced or lost loved ones to gun violence. In April, they spent almost 13 hours waiting to testify in favor of gun reform before the Texas state House committee, where Democratic state Rep. Joe Moody shared horrific details from an inquiry into the shooting conducted by lawmakers.

All the while, the group has continued sharing the stories of their loved ones with others to amplify their message. “Our work is at the ground-level,” Mata-Rubio says. “It’s moms saying, ‘Hey, if you’re a mom, a dad, a sister, a brother, then this is your fight. Join us.’”

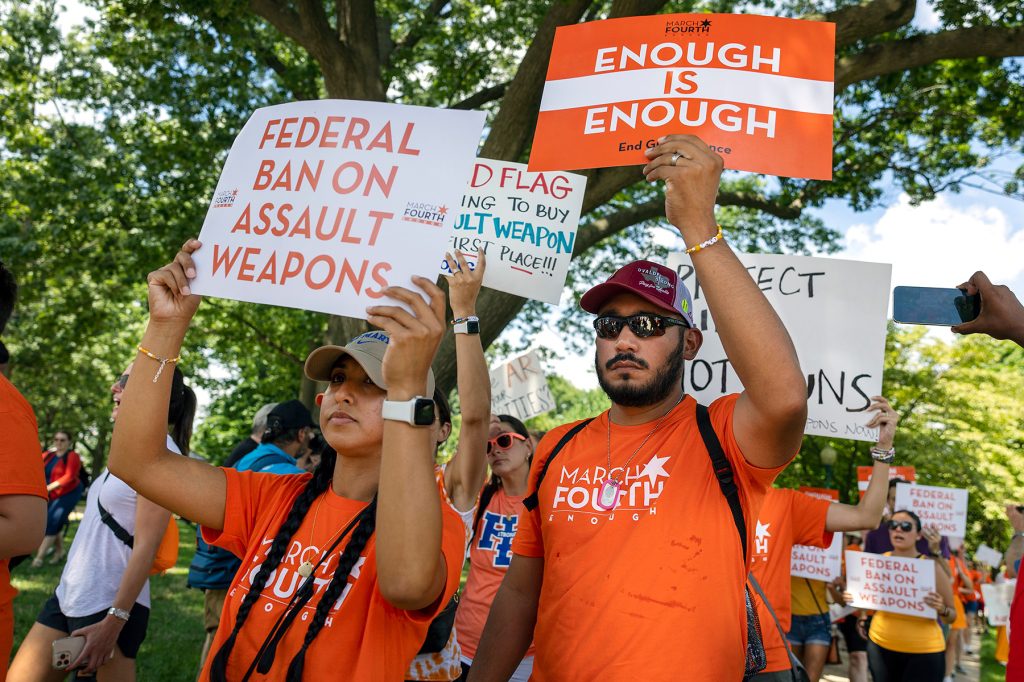

Kimberly Mata-Rubio, who lost her daughter Lexi in the Uvalde, Texas school shooting, marches in a rally calling for a federal ban on assault weapons on July 13, 2022 in Washington, DC.

Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Still, the work hasn’t been easy, and it hasn’t always been well-received, especially in their own community of Uvalde, where gun reform conversations are contentious. “Uvalde’s that town that just doesn’t like change or doesn’t like to [stir] the pot, so to speak — just leave things alone, leave things the way they are. And so, when things like this happen, people just don’t understand the affected,” Arreola says. Historically, the county has backed conservative values, voting for every Republican presidential candidate since 1968.

The community grew more divided as details about the incident continued to emerge. State and local law enforcement officials delivered a shifting, muddled explanation about what happened. In June 2022, video came out showing that law enforcement officials waited 77 minutes to confront the gunman, who barricaded himself between two adjoining fourth-grade classrooms. Several children, including Amerie, reportedly called 911 and urged police to help them.

A joint investigation by the Washington Post, ProPublica, and the Texas Tribune found evidence that, in addition to law enforcement’s delay confronting the shooter, there were also communication lapses, systemic failures, and a lack of critical resources that kept victims from getting immediate medical treatment. According to documents they uncovered, a girl matching Jackie’s description likely survived for more than an hour after she was shot. But by the time medical personnel reached her and put her in an ambulance, it was too late: She died on the way to the hospital.

In December, a group of survivors and family members filed a $27 billion class-action lawsuit in federal court against the town of Uvalde, the school district, and multiple law enforcement agencies and officers. The lawsuit cites “the indelible and forever-lasting trauma” of survivors and the families of the victims. Meanwhile, DPS has not provided an update on its official investigation, despite promising it would wrap before the one-year mark. “We haven’t heard anything at all,” Mata says disappointedly. “We hope that we’ll hear something soon, hopefully that we’ll get something by May 24, but they’ve been stonewalling that as well.”

The families have instead focused on specific legislation. In May, they appeared to make some progress toward passing House Bill 2744: In a last-minute vote, the bill passed out of committee 8-5. Though the Texas Calendars Committee missed a deadline to set a date for the House to vote on the bill, some Democrats have promised to continue trying until the session ends on May 29. Moody, for example, went on the House floor in May and proposed adding the age cap to another existing gun reform amendment as a way to get it across the line.

None of this has dissuaded the parents of Lives Robbed. “Just like we can never turn around and see our daughters again, we’re not going to turn around and walk away,” Mata says.

Cazares knows the work they’re doing is exhausting. “It’s emotionally draining. Being out of town or doing these hearings or talking to the representatives, lobbying, it’s extremely difficult,” she says. However, her plan is to keep going to honor Jackie. “I didn’t choose to do this, she says. “But I really don’t have a choice now.”

AS THE ONE-YEAR ANNIVERSARY of the tragedy approaches, the members of Lives Robbed have been planning activities to honor their children and loved ones. That hasn’t been easy: “It’s very hard knowing that we’re going to have to relive that day again pretty soon, and we know that it’s going to be a total nightmare,” Arreola says. “It’s going to be deja vu of that same day.”

Family members constantly have to relive the trauma of May 24, 2022. Arreola says she’s uneasy these days, constantly thinking about the dangers of gun violence. “That day changed my whole entire life and my whole way of thinking, my demeanor, my attitude,” she says. “I walk into a place that I’ve never been. I’m looking to see where the exits are. I go to a parade and I’m looking up at the buildings, making sure that there’s nobody up there.”

She even felt nervous entering the D.C. Capitol, where she eyed armed security standing at every entrance. “I mean all the law enforcement agents, officers with guns, you don’t feel safe because how do I know you’re going to protect me? You didn’t protect my grandchild. How do I know you’re going to protect me? You don’t feel safe anymore because your trust is gone.”

Gloria Cazares and Berlinda Arreola

Courtesy of Lives Robbed

In her kindergarten class, Mata has had to run through lockdown drills with her students throughout the year. On the day she spoke to Rolling Stone, she had been shopping at the local HEB when suddenly there was an announcement that the grocery store was going under lockdown because of a police incident nearby. Mata noticed a friend with her young daughter on one side of the store; the daughter had been a student at Robb Elementary who was across the hall when the gunman entered. “She was trying to be strong, but you could see the fear in her eyes and her face,” Mata says. She stayed with the friend and the girl in the bathroom until they were allowed to leave after about 10 minutes.

Despite these difficult moments, they’ve forged ahead to honor their children. On May 24, they’re planning a candlelit vigil with members of the community at the Uvalde Memorial Park Amphitheatre. There will be a few musical performances to honor the lives lost, as well as some speakers who will share memories and reflect on their family members.

Mata hopes that these events will preserve the memory of each victim: “We want to be able to honor all of them in their own special way, because they were each individual kids,” Mata says. She wants people to remember all the qualities that made them special: “We want to make sure that people remember that Lexi loved to play softball with her dad, and Jackie wanted to go to Paris, and Amerie wanted to be an artist. Tess loved watching medical shows. Her favorite player was José Altuve, “she says. “They were our kids. We want to make sure that they’re never forgotten.”