The standing ovation was inevitable.

Not just because audiences getting to their feet and applauding has felt perfunctory and expected for decades. Pass Over is being lauded as the first play staged on Broadway since the coronavirus pandemic forced all live performances to stop in March 2020. And at the top of this performance during the official opening Sunday matinee at the August Wilson Theatre on August 22nd, the thousand or so people in attendance were greeted and welcomed and congratulated for being “one of the first audiences back to see a real Broadway play.”

So we were all enthusiastically clapping not only for the three actors on stage, the dedicated crew and slew of people it takes to put on a production, we were applauding ourselves. Despite all of us wearing face masks, the rejoicing (and relief) couldn’t be muffled: We did it. We gathered together in a dark room for over 90 minutes and laughed and cried and witnessed live theater together once again.

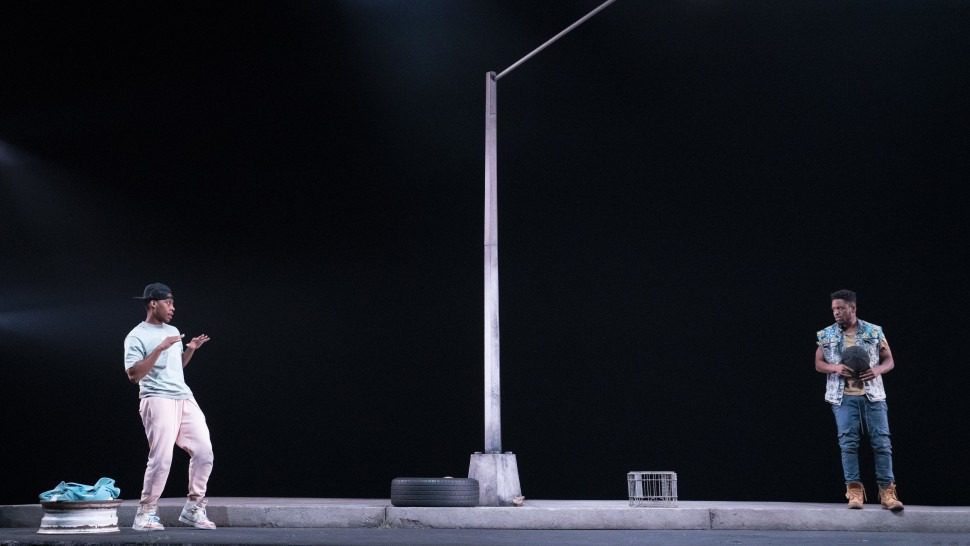

Antoinette Chinonye Nwandu’s play (starring Namir Smallwood as Kitch and Jon Michael Hill as Moses) is an important one not only because it will forever have this historic milestone as part of its pedigree. Originally produced by Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago in 2017, then filmed by Spike Lee (and streaming on Amazon), and later revised for Lincoln Center Theater in 2018, it’s a story of two young Black men in peril and in constant fear of police violence. In director Danya Taymor’s thrilling production, the play — which takes inspiration from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot as well as the Book of Exodus — audiences are confronted with a mostly bare stage, except for a towering street light, as the two men trapped on a city block tell stories, play games, eat a sinister picnic (shared by a sinister white man named Mister/Master, played by Gabriel Ebert) and desperately try to escape by any means possible.

Namir Smallwood (left) and Jon Michael Hill in ‘Pass Over’ on Broadway.

Joan Marcus*

For its Broadway debut, Nwandu revised her allegorical script with a more “optimistic” ending. “While Trump was president and there was no vaccine and George Floyd was being murdered, lynched, I could not see another ending.” she told NPR. “I can imagine an Afro-futurist ending of my play that exists within the bounds of the world I’ve already created, where this young Black man could actually live.”

But the fact that the play is even having an opportunity to open at this time — amid the pandemic — still feels incredible in its own right. And much of that can be to the efforts of a slew of people who are testing, protecting, and securing the cast and crew and staff against breakthrough Covid-19 as the highly infectious Delta variant is rampaging across the globe, causing many people to question whether gathering together in enclosed spaces is such a smart idea.

Blythe Adamson, an epidemiologist and economist who’s spent her life dedicated to the prevention of infectious diseases and reducing risk, has been working with the producers to put strict Covid protocols in place so that the production could operate safely and welcome audiences back to a packed theater.

“If we want to live a life with no risk, then we can stay inside our apartments all day alone and isolated, with no community,” Adamson explains. “It’s completely understandable that people may feel anxious when returning to being in a crowd. That’s why we’ve layered together so many different strategies to help them feel safe.”

Adamson hired a former stage manager, Charlene Speyerer, to join her team at Infectious Economics to develop strict protocols for the cast and crew, from rehearsal and pre-production through opening. And they trained longtime stage manager and industry stalwart Pamela Remler to be Pass Over‘s Covid safety manager, a new position that was created as other industries have done to bring rigor and confidence to a confusing and ever-evolving area.

The actors on stage are receiving Covid PCR testing daily, and the crew and everyone else involved are also being tested and monitored by Remler. “Our building is the safest building you can walk into,” Remler says, explaining you don’t know the vaccination status of the people in grocery stories and other places we often gather. “In my opinion, I would come see this show every single day and I wouldn’t sit in a restaurant until everyone is vaccinated and/or masked.”

That confidence and vigilance still isn’t enough for many who remain dubious about whether it’s worth the risk and headaches of schlepping to a theater in Midtown Manhattan to wait in the rain, go through a metal detector, show valid proof of vaccination, and then sit in less-than-comfortable seats with a mask over one’s nose and mouth the entire time. And yet thousands of us have since the show began previews at the beginning of August.

Although Pass Over has obvious connections to Godot, it was another allegorical play about existential dread, Sartre’s No Exit, that I found myself pondering while I sat crammed in the orchestra that Sunday afternoon, the person to the right accidentally touching my arm and both of us flinched at unwanted human contact. That play’s message — that “Hell is other people” — surfaced in my mind as I tried to stay focused on the talented actors on stage. It made me wonder why so many of us did feel so determined to gather together like this.

Then I remembered what Cody Renard Richard, Pass Over‘s stage manager, told me about being in a theater, which is a form of church for so many. “The positive energy really is palpable,” the 33-year-old Black man says of the production’s significance to him and others. “When you make art, when you’re on a show, you do it because you love creating. … You just do it.”

And that’s why we’re working so assiduously to overcome our suspicions and trepidations at being around others. Hell may be other people in many ways — especially as we work to combat so much disinformation and fear-mongering — but being with other humans can also be a glorious experience. One for which many of us are grateful to have once again.