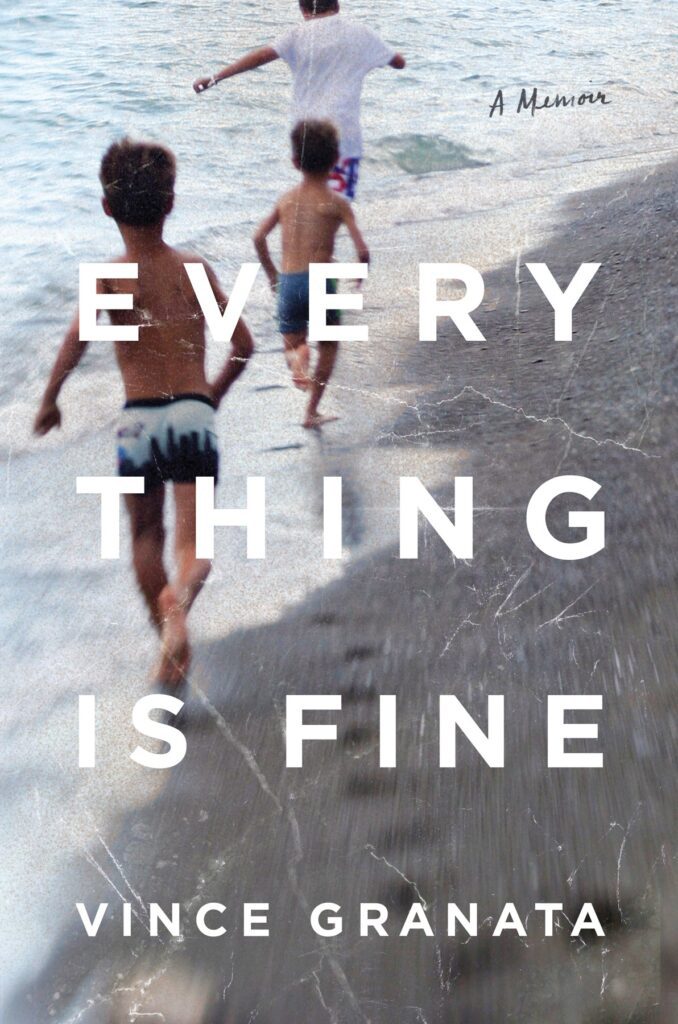

In his new memoir, Everything is Fine, Vince Granata explores grief, mental illness, and the bonds of family as he delves into the tragedy of his mother’s 2014 death at the hands of his schizophrenic brother, Tim. Using a mix of personal essay and journalism, Vince pieces together his mother’s life, his brother’s illness, and ultimately, begins the process of salvaging his love for his brother. In this excerpt, Vince goes to see Tim at Whiting Forensic Hospital, visiting his brother for the first time since their mother’s death.

***

It was dark when I drove to Whiting for the first time. Three months had passed since our mother’s death.

As I approached that first night, the brick buildings looked hollow, like old warehouses in an abandoned mill town. Whiting had grown out of the state facility for the mentally ill, a compound that opened in 1868. Many of the old structures still line the campus — late-Victorian architecture, broad brick buildings, nineteenth-century boarding school meets asylum. Whiting is on the back side of the campus, on the downslope of a hill near where the Connecticut River bisects Middletown.

After the final turn — Sweet Drive, the road at the entrance of the facility — I saw a rectangular transformer, a steel box flanked by knots of coiled wire. I passed a police cruiser before turning into the parking lot.

I chose a space away from other cars. The lot slopes gradually downward in the direction of the entrance; the decline pulled me to- ward the building’s main door. From street level, I could see only one long wall, the concrete extending away from the parking lot. Once inside, I learned that the compound is an angular parallelogram, each side a long corridor bounding an inner courtyard with grass, a concrete basketball court, a seasonal garden.

At the front entrance, a voice behind a camera asked me questions.

Who are you here for? What is your name?

I answered, staring back at the circular camera lens, a lidless red eye. The door buzzed, the sound a low hum, like I was being let into a friend’s apartment building.

Inside, I stopped to scan the waiting room — chairs, green carpet, framed photographs of former wardens. A glossy copy of Parenting magazine sat on an end table.

I stared at a bulletin board that celebrated the clinician of the month. The winner, a freckled woman with full cheeks, looked like a school nurse, one who spent her afternoons comforting kids with upset stomachs.

I let my eyes travel the rest of the room, scan the plaques commemorating distinguished employees, a glass case housing a ceramic Virgin Mary, a series of nesting dolls, a miniature Buddha. I noticed a metal detector, a machine standing like a sentry before a wall-size door. I fixated on these details, let the contours of this broad metal door distract me from the questions I had for Tim.

I had a strategy for this first visit, a strategy that would keep me focused and prevent the details of my mother’s death from interfering with my mission — Help Tim remember, help him be restored. I crafted a list of innocuous questions, a warm-up I hoped to perform before approaching the business of memory.

As I waited, looking toward the metal door, I heard a voice but couldn’t see its source.

“Vincent?” my full name, one I rarely heard, traveled through opaque glass next to the metal detector. Soon a corrections officer appeared.

“Come through the detector,” he said.

It beeped when I shuffled through. I moved my hand to my belt buckle like I was explaining myself to airport security. Behind the glass, three uniformed officers scanned a bank of monitors. After I’d handed over my driver’s license and emptied the keys, gum, and ChapStick from my pockets, the mechanized door inched open. I cleared a second mechanized door and a voice from behind the glass told me to keep walking until I saw the visiting room on the right.

Along the sterile hallway, open doors revealed offices, a nurse’s station, a Xerox machine. I smelled stale coffee, passed a water fountain, a pegboard with key chains, a janitor’s closet. I had expected more—patrolling corrections officers, conspicuous cameras, locked doors.

There was no choreography to my reunion with Tim. No one stood at the entrance of the visiting room waiting to point at my brother and say, “There he is,” or, “Tim will see you now.”

Yet there he was, Tim, on the other side of the door, sitting like he had been waiting for months.

When I’d seen Tim in news clips from his first court appearance, his hands and feet were bound. He shuffled when he walked, head bobbing up and down like he was following music that only he could hear.

I saw him now, completely unfettered.

Without restraints, Tim pushed himself off his chair and stood behind a low table. He waited. The collar of his sweatshirt hung limp below his unshaven neck.

He was in gray sweats, not the standard jumpsuit I’d seen him wear in the news clips. He had dressed this way at home, sweats draped over bulging muscles.

“Hey, man.”

After a few steps, I felt his arms wrap around my torso. We hugged, and I remembered how in high school, when he was just starting to realize his strength, he would squeeze me harder and harder until my laughs turned to gasps. Now I felt little pressure, only the weight of his massive hands spread across my back.

The room was spare — cinder-block walls, dark heavy carpet. It felt like an assembly room, one that might be in a church or com- munity center or town hall, a place for coffee in Styrofoam cups. We were alone except for one corrections officer perched on a small platform to our left.

When we sat, our shins pressed into the wooden table separating us. Later, Tim would tell me that the tables were placed this way to prevent one person from lunging at the other.

We laughed during that first visit, almost immediately after we sat down. At first, I wondered what the corrections officer was thinking—two brothers bent over a prison table, one a killer, both laughing. I glanced at the corrections officer and saw his eyes locked on a walkie-talkie in his lap.

“They let you have your own clothes here?” I pointed toward Tim’s sweatshirt.

“They gave me these,” he said.

“They know your style.”

“Pretty much. Pretty much.” He laughed, pushing air out of his nose.

When I watched Tim laugh, I realized for the first time that he lived in the same body. When I’d seen him in courtroom video clips and in newsprint pictures, he had looked the part the headlines had cast him in, that of deranged killer. He wore a jumpsuit and hand- cuffs, his glasses falling toward his nose in an image that thousands of people would see. Psycho, they would say, and how could I blame them when all they saw were those pictures? How could I blame them when the only Tim I had seen was the monster that visited when I slept?

But sitting across f rom him in the visiting room, I saw that he had the same olive skin, the same black hair, a shade darker than that of everyone else in our family. He still had the same cauliflower ear, a mass of crushed cartilage above his right ear canal, a common marker among many competitive wrestlers.

And there was something else, a barely perceptible suggestion of who Tim used to be, a softness in his cheeks and on the skin under his eyes. His mouth didn’t quiver in agitation, ready to loose a diatribe on original sin, on the immense distance we lived from Christ. There were no sharp head nods, no twitches of response to invisible stimuli.

“How’s the food?” I asked, remembering his rigid adherence to chicken breasts and egg whites when he was wrestling.

“It’s not that bad,” he said.

“How’s your back?” This was chronic pain, shooting sciatica, something he had mentioned when he spoke at his arraignment, months before. The judge had asked him if he had any physical problems.

“I have a lot of joint pain and a bad back,” Tim said. This line, Tim’s response to the judge’s question, was printed in several of the newspaper stories, Tim’s sober assessment of his physical injuries.

“Not bad,” Tim said. “I don’t move so much in here.” He minimized his pain as he had after high school wrestling matches, bags of ice strapped to his shoulders, his badges of honor. This had been an easy conversation for years, the discussion of his physical aches, the bruises sustained as an athlete. The physical was always easier, easier than when he would tell me that he spent all his time in his room because he was afraid to meet new people.

“Do you have a roommate?” Roommate made it sound like college, where the guy in the bunk below him might be from Michigan or Delaware, might have a different major.

“There’s one guy. His name is Bill.”

Later, I would learn about Bill. During a psychotic episode, Bill had shot and killed a college student at a campus pizza shop. A few visits later, I met Bill’s family in the waiting room. They were kind to me, extended easy empathy, a type of understanding that can pass between fractured families, between people trying to find their lost loved ones.

“There’s an overhead picture of this place in the waiting room,” I said. “I saw a big courtyard. Do you go out there?” I realized courtyard sounded like I was talking about a sprawling campus.

“They give us time out there,” Tim said. “I usually just walk around.”

When I ran out of easy questions, I moved to more intermediate ground. I mined the deep past, memories he might still have, memo- ries recent years hadn’t blemished.

“I saw John the other day,” I said, mentioning our godfather. “He was in town showing Sean colleges. Do you remember him?”

“Yeah, I think so.” Tim squinted like he was trying to see some- thing behind my right shoulder.

During the first times I visited him, those three words — I think so — were Tim’s most common phrase. They were always paired with some sign of effort — eyes narrowing, drawing a wrinkle on his forehead.

I told Tim about a friend who had gotten engaged. “You remember my friend Andrew, right?”

“I think so.”

“He’s getting married. It’s bizarre, everyone is getting married now.” I laughed a bit.

Tim laughed too, lifting from where he sat in the chair. When he settled, his weight sank more conspicuously in folds creasing his gray sweatshirt.

“Do you think you’re ever going to get married?” Tim asked.

“Maybe. Someday.” I was growing distracted, worried that I was reaching the end of the questions I had prepared. There was only one left.

This last question was different. It involved our mother. Mentioning her to Tim, bringing her between us, terrified me. We had been speaking for thirty minutes, and she had yet to enter, my warm-up questions a strategy purposefully employed, one that would help move us gradually to her, to fraught ground.

But everything was fraught ground. We were speaking for the first time in three months, for the first time since he’d left our mother bound and broken on the family room floor. Could I have asked him then if he remembered when we were kids, clamoring with Chris around the computer in the family room, taking turns with the mouse, standing in a semicircle around the spot where our mother would die? Could I have asked him if he remembered her last words?

This hesitance was why I had my warm-up, this gradual opening I’d thought was for Tim. I’d thought that we could work out some stiffness in his mind, limber him up, before we tested heavier memories.

But the warm-up was also for me. I needed to be able to pretend, if only in a small way, that I wasn’t meeting Tim at a psychiatric prison, that I wasn’t visiting him months after he’d killed our mother, that I wasn’t trying to coax him into a conversation that we would have for the rest of our lives.

Remembering was necessary, the only way, and though I wanted to save him this pain — the pain of remembering — his restoration demanded otherwise. This process could only start when he could stand trial, when he could be acquitted on grounds of insanity, when he could begin what would, in a best-case scenario, be a twenty- year period of incarcerated treatment. At forty-three he could walk out of this building and into my car. We could drive away into the afterward, fully restored. This process was the way I would get him back, the best way to honor our mother, to get him back because she never would.

I hadn’t yet realized that this clear-eyed hope for recovery was just the most recent in my own string of delusions, a long string winding through years of naïve hopes. I see the beginning of my delusions, sitting next to Tim in the dent he made in his bed, hugging him the day after he first told our mother that he planned to die on the Fourth of July.

But I still thought that I could reach him, sitting across from him in that visiting room, as close as when we were children paddling a canoe. I thought that I could reach him because our mother no longer could. I thought that because I had hugged him, been close enough to smell his dried sweat, that he would understand why I had to ask my next question, my last question.

When I asked him, I knew that I couldn’t use the word remember. “Do you miss Mom?”

I had conceived this question as a ploy, a calculated tactic I thought might trigger a rush of memory. But as soon as Mom left my mouth, I realized that I wanted an answer.

“I wish I could have gone to her funeral,” Tim said, “but I was here.”

I looked at his eyes, the dark points of his pupils. The only one having a sudden rush of understanding was me, face-to-face for the first time with the complications of his frayed memory. He could know that she was dead but repress that he had held the knives.

“How was it?” he said, like he was asking about a movie he hadn’t seen.

“The music was beautiful,” I said, peeling my eyes away from his, letting them settle on the table between us.

That was as far as I went the first time. Soon he was asking me about how long it would take to get back to Boston. Then we stood, hugged, his massive shoulder cradling the bottom of my chin.

I told him that I would be back in a week.

As I walked to my car, I tried to remind myself why I had visited. I tried to remind myself about my mission, the task I had set.

I’m visiting to help him remember, to help him be restored.

I’m visiting for our mother because she never got him back.

I’m sure I wanted these things, for Tim to be restored, for me to act, somehow, as our mother’s proxy.

But those reasons alone didn’t bring me to the visiting room. I know that now.

I was the one who needed Tim restored to my life. I was the one who wanted Tim back.

I had been looking for him during the entire visit.

From the forthcoming book EVERYTHING IS FINE by Vince Granata. Copyright © 2021 by Vincent Granata. Published by Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Reprinted by permission. Find the book here.