By the year 2000, there were no more pages in the pop star rulebook for Madonna to rip up. At no point in her nearly two-decade career had her star begun to dull; 1992’s Erotica was, by Madonna standards, a flop, but it still peaked at No. 2 and spawned two top 10 hits. She followed it up with 1994’s R&B-influenced Bedtime Stories and its single “Take a Bow,” which stayed atop the Hot 100 for seven weeks. With 1998’s Ray of Light, she claimed to be stepping away from the trappings of pop star life—and still, somehow, wound up more famous and more influential than ever.

Madonna’s pivot on Ray of Light was wildly successful, her Britpop-suffused entry into the world of Eastern spirituality and clean living cannily marrying the tastes of a culture as interested in Pure Moods as Oasis. As a rebrand—from the bratty transgression of her early career to a serene, anti-individualist earth mother—it was almost too successful. For the first time, Madonna was up in the clouds, presiding over her pop kingdom from afar, seemingly uninterested in the vagaries of the modern landscape. Although Ray of Light produced three undeniable hits—its title track, the steely, lovelorn “Frozen,” and all-timer power ballad “The Power of Good-Bye”—the reserved persona necessitated by Madonna’s more self-serious music had also stamped out some of her sense of fun.

No matter: As ever, Madonna had more cards to play. On 2000’s Music, the wise, newly magnanimous superstar came back down to earth and, naturally, the club. Capitalizing on the gargantuan success of Ray of Light, Music managed to maintain Madonna’s newly mature image while reinjecting her sound with fun and freedom. It wasn’t a reinvention, exactly. Instead, Madonna proved that she could be a 42-year-old mother of two and still be as sexy, silly, and provocative as she’d always been. “There’s nothing sexier than a mother—Susan Sarandon, Michelle Pfeiffer, I mean, those women are sexy,” she told People in March 2000. “I’m in better shape than I was at 20.”

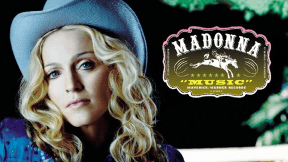

On Music, Madonna presented her vision of global heartland music. The cowboy getup she wore throughout this era isn’t tied to any overarching country influence; instead, think of it as a (slightly gaudy) symbol of humility, an indication that this record is something real and vital. This was an album designed to unite the disparate tastes of America and Europe, to act as a bridge between teen pop and sophisti-pop, the mainstream and the underground. Across Music, Madonna infused French touch with the sleazy grind of R&B, reinterpreted Americana through the lens of Timbaland and Aaliyah’s warped pop experiments, and put her spin on the clean, heartfelt ballads that the Titanic soundtrack had pulled to the top of the charts. An album comprised entirely of earnest balladry and heaving club tracks, it became one of Madonna’s final world-beating successes—a flexing of artistic muscle that holds its own alongside her most electrifying, epoch-defining records. “The world is in the doldrums musically. It’s all so generic and homogenized,” she told Billboard at the time. “If this record happens, it might mean that people are ready for something different.”