As pop and politics clashed to fight for sexual liberation and queer visibility, some distinctive and brave new voices emerged as the loudest, whatever the repercussions… here we look at 1984 – The Year Pop Came Out

Looking back at the kaleidoscope of colourful characters that epitomised the gender ambiguity of the early 80s, it’s easy to mistakenly credit them the seismic shift in attitudes towards sexual politics that reached its crescendo in 1984. While there’s no question that the New Romantics, with their scintillating synth-pop and immaculately made-up visages, or Adam Ant and Siouxsie Sioux making fetish-wear fashionable sparked debate about gender norms and sexual identity, they were more about fashion statements than political ones.

As devotees of Bowie, Bolan and glam rock, the bright young things monikered the “gender benders” by the press adopted the tropes of their predecessors, blurring the lines between what it was to be masculine and feminine with their outrageous attire, but in 1984 it was still very much a case of style over substance. For many of those that would later find the courage and the voices to become progressive forces of a new era of queer liberation, it was not only in vogue to be vague, it was imperative to achieve success.

Fight For Equal Rights

“In the early 80s you were signed to a record label and told you had to invent girlfriends, and if you didn’t radio would never play your records again and you’d be ostracised by the press. In short, your career would be over,” Marc Almond told The Herald. “I didn’t want to say I wasn’t gay, but I didn’t say I was gay either. And on top of that, I didn’t want to be defined as a ‘gay artist’. I just wanted to be a pop singer. I didn’t come out publicly until 1987 and I wish I’d done so sooner.”

Almond was just one of the successful artists who later used his platform to fight prejudice and seek equal rights for the gay community. Flamboyant in their fashion but subdued in their public views, Boy George, Elton John, George Michael and Freddie Mercury telegraphed gayness but were hiding in plain sight in ’84.

Whenever the subject of sex was raised in interviews, Boy George, at the time the asexual, family-friendly pantomime dame of pop, was on hand with a witty riposte such as he “preferred a cup of tea to sex” while behind the scenes, his turbulent relationship with Culture Club’s drummer Jon Moss was the source material for many of the group’s hits. Elton John, who had previously admitted to being bisexual, married studio engineer Renate Blauel and George Michael stopped shoving shuttlecocks down his shorts and dressing up as an airline pilot to cultivate a safer image (complete with an identikit Princess Diana haircut) and paraded a stream of glamorous girlfriends.

Breaking Free

Although revered as one of rock’s most flamboyant frontmen, Freddie Mercury never publicly addressed his sexuality, accompanied to most public events by ‘soulmate’ Mary Austin. 1984 was the year he famously persuaded his bandmates (incidentally, naming the group Queen was always intended to mean regal rather than the often-misunderstood double entendre) to dress in drag as Coronation Street-type characters for the video to I Want To Break Free and was heavily influenced by underground gay clubs for his solo material. He was a regular at New York’s S&M clubs such as The Anvil and Mineshaft and not only appropriated the look of the clubs’ patrons, the moustache and tight vest, but also the pumping hi-NRG soundtrack for his solo material.

“I don’t blame them [for hiding their sexuality] because everyone was terrified,” Almond continued. “Then Jimmy Somerville came along, and he really put himself on the line, singing about openly gay themes. He was incredibly brave while the rest of us were hiding behind the eyeliner!”

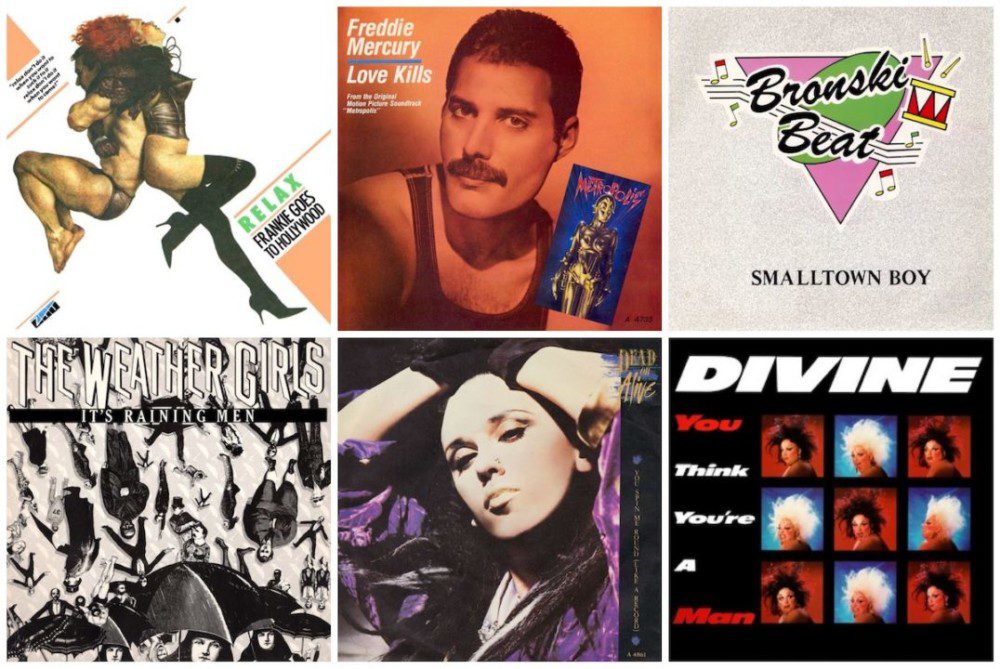

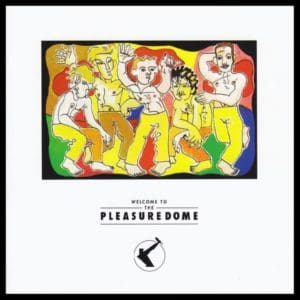

The releases of Bronski Beat’s Smalltown Boy and Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Relax were pivotal in highlighting gay visibility, with the band’s frontmen, Jimmy Somerville and Holly Johnson respectively, the out and proud voices needed to speak out against the prejudice levelled at the gay community. In terms of visibility and representation, gay men were largely still portrayed as camp and effeminate, the punchline to the jokes on campy sitcoms. Though fighting the same cause, their approaches were very different. Bronski Beat’s came from the heart, Frankie’s from the groin.

Relax, Don’t Do It

“Frankie Goes to Hollywood were really the first ones who came out and said, ‘Well, yeah, we’re gay.’ And it caused a shockwave, but it also didn’t hurt them – it did the opposite. It propelled Relax to being huge,” Bernard Rose, director of the Relax and Smalltown Boy videos, told Yahoo Music. “Bronski Beat were around before that happened, but their record came out after, and they were coming out into a market where the Frankie thing had already happened. I don’t exactly think it was like their thunder was stolen, but they weren’t the first. But I do think their approach was much more politicised and much more serious.”

While Relax was very animalistic, the pounding, hi-NRG beat and sexual lyrics was enough to get the record banned by the BBC before the video, set in a S&M club and exploring various fetishes, even entered the equation. Bronski Beat, on the other hand, dealt with the emotional side. The haunting lament of Smalltown Boy dealt with the brutal reality of being ostracised for being gay and though Jimmy Somerville’s own story, it spoke to the misfit in everyone. The follow-up, Why?, was a militant attack on homophobia and prejudice – “Contempt in your eyes as I turn to kiss his lips… Can you tell me why?”

Tell Me Why?

Because Somerville essentially embarked upon a music career as a happenstance of his activism (he began singing while filming a documentary about homosexuality called Framed Youth: The Rise Of The Teenage Perverts), he was out and proud, a dangerous cocktail that earned him disdain not only from the public and press, but also from his peers, even those still in the closet. Whether it was a result of jealousy or fear on their part, he spoke openly in interviews of dirty looks and homophobic comments backstage at Top Of The Pops or award shows.

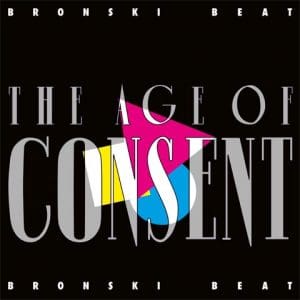

Rather than be diminished or silenced for his sexuality, he was unapologetic, openly lusting after other pop stars in the pages of Smash Hits, calling the band’s album The Age Of Consent to highlight the UK’s regressive stance on gay issues and featuring the telephone number of the Lesbian & Gay Switchboard on their records.

Thatcher’s Britain

The fact that he was experiencing such hostility and vitriol in what was deemed a much more progressive business shone a light on how hostile life was for gay people in Thatcher’s Britain. Under fire in the press, from the police and politicians, it is little wonder that in the face of such persecution and prejudice, gay people sought solace in music.

One of the most primal ways to express themselves and experience the sheer joy and liberation arrived in the form of hi-NRG, a direct descendent of disco with a tougher, more electronic sound. Obviously influenced by Giorgio Moroder, it had become the sound of the gay underground scene for a couple of years. Its breakthrough into the mainstream further evidenced acceptance of gay culture. Originating in San Francisco by DJ/producer Patrick Cowley at his Menergy club nights at The EndUp in 1982, hi-NRG (originally called hi-NRG Disco) was an up-tempo take on disco with the hi-hat removed, replaced by a harder bass and the inclusion of a staccato synthesizer and handclaps.

Two hugely influential DJ-meets-drag partnerships, Patrick Cowley with Sylvester and Bobby Orlando with Divine, helped populate the sound. While disco classics spoke of hardship, pain, and emotional defiance in the face of adversity, this new variation was its sluttier sister injecting a sexual frankness into the lyrics. The style quickly took off in New York clubs such as The Saint before making its way to Europe thanks to influential DJ Ian Levine, who packed his sets at London’s Heaven nightclub with tracks such as Sylvester’s Do Ya Wanna Funk?, Divine’s Native Love (Step By Step) and Passion by The Flirts.

Heaven Sent

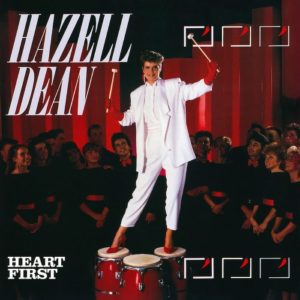

As songs that had dominated the dancefloors of these gay meccas for well over a year made their way into the Top 40 singles charts, the transference of gay culture proved lucrative (later dubbed “the Pink Pound”). Hazell Dean’s Searchin’ (I’ve Got To Find A Man), Gloria Gaynor’s I Am What I Am and The Weather Girls’ It’s Raining Men were all massive hits. Ian Levine enlisted US diva Evelyn Thomas for High Energy, a track which immortalised the genre over a beat remarkably similar to Frankie’s Relax (though Levine maintains he was influenced by the Village People’s In The Navy).

As hi-NRG crossed over, it transcended the big cities and became the predominant sound of the clubs across the country. DJ and aspiring producer Pete Waterman was in a gay club in Coventry in 1983 when he first heard hi-NRG. “I was watching the marketplace from a punter’s point of view,” he told The Spectator. “New Order’s Blue Monday was just happening, and I was thinking, ‘Look at this, there’s something going on here’. I had a good four to five months watching the marketplace as an insider almost.”

The revelation became the impetus of one of music’s most successful teams of all time. In January 1984, Waterman had enlisted songwriters/producers Mike Stock and Matt Aitken and together they came up with a formula that married the dance sound with pop melodies. “Most examples of hi-NRG were short on song,” recalls Mike Stock. “I was keen to bring structured songs into the style. We saw the club scene as a genuine way to reach people who might buy records. We took forward some of the dance elements into the more pop projects.”

The Hit Factory

Their formula became Stock Aitken Waterman’s gateway to pop success. “We weren’t brazen enough to think we could take on EMI or Warner or the big companies,” Waterman states. “That never even came into our thoughts. We just knew the major record companies were not focused on a market I knew well and loved – the gay dance market. They weren’t interested.”

By the summer of 1984, SAW had achieved a UK Top 20 hit with Divine’s You Think You’re A Man, the first but not the last hi-NRG star to bolster their roster. Hazell Dean’s Whatever I Do (Wherever I Go), the first hit they’d also written, broke the Top 10. Both of those records were instrumental in attracting Dead Or Alive after Pete Burns fell in love with them. After presenting them with a demo of You Spin Me Round (Like A Record) and an order to “make me sound like Divine”, the song topped the charts – a first for both SAW and Dead Or Alive.

Out & Proud

As is often the case when an underground phenomenon translates into mainstream success, it instantly loses its cool factor. Critics were already writing hi-NRG’s obituary, wildly prematurely as it turns out as it not only was a template for many big hits to come, but also the foundation for SAW’s unstoppable run of hits spanning the rest of the decade and beyond (it has to be said, courtesy of a string of ‘safe’, pop-star-next-door types).

Obituaries were sadly becoming all too common as the year drew to a close with gay nightlife decimated by the spread of HIV and AIDS which was wiping out gay men in droves. Aside from the utter devastation and tragedy of the deaths themselves, the ‘gay plague’ tag had an immeasurable impact on a community already under attack. Gay people were once again shamed and vilified, eradicating much of the progress of the past couple of years. Although some very tough times were still to follow, the merging of pop and politics ensured that 1984 was undoubtedly the year pop kicked open the closet door, and it was never closed again.

For LGBTQIA+ mental health support click here

Read More: Make It Big: The Story Of 1984

The post 1984 – The Year Pop Came Out appeared first on Classic Pop Magazine.