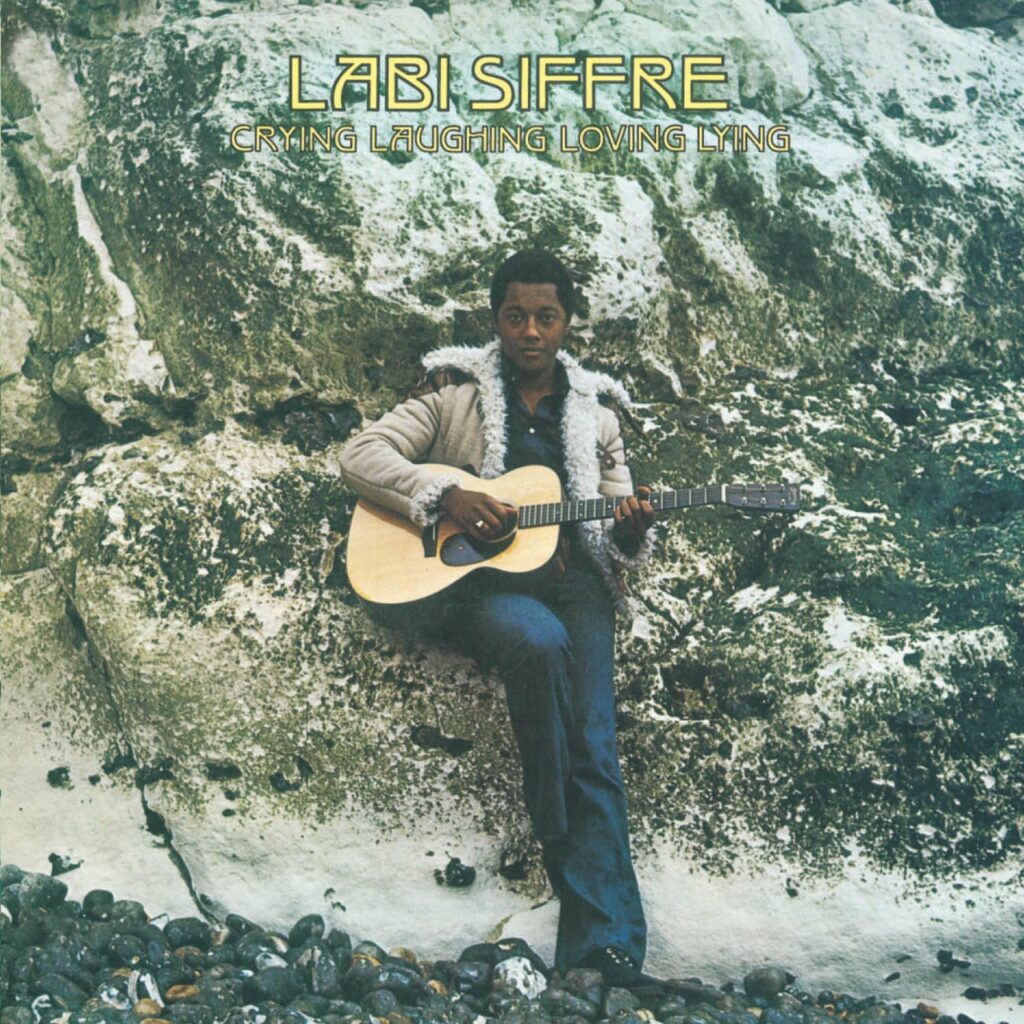

“There are things you can say in a song that you would be too embarrassed to say in conversation,” Labi Siffre told a BBC interviewer in 1972. “In a song you can say it and it sounds correct. It’s a cowardly way of saying things one would never say.” Delightfully unpretentious, Siffre sits in a gray collared shirt against a window overlooking a thicket of trees, still fresh-faced at 27 years old and already sharply perceptive of the vulnerability of his own folk music. He’s being a little playful, quoting a song of his own at the end. His confidence is earned: He had just released his exquisite third album, Crying Laughing Loving Lying, the record which introduced him as a generational talent, one who over the next 50 years would create timeless music that’s become a touchstone for his folk descendants, pop superstars, and rappers alike.

Born in 1945 in Hammersmith, London, to a Nigerian father and multi-racial mother from Leeds, Siffre was the fourth of five brothers. He followed in their footsteps and attended a religious school that proved an ill fit for the artist. “I was brought up to have low self-esteem,” he once said of growing up as a gay kid surrounded by rigid Catholic ideology. “I grew up being told by society that as a homosexual I was a bad, wicked, evil person.” The experience led him to become a lifelong atheist; he recalled being bemused at how people believed in an omnipotent man who “does magic tricks of life or death.” For Siffre, his emotions and beliefs mattered most—mindfulness of those around you, political engagement, love and compassion. He identified as gay as early as 4 years old, a sheer, unalterable fact that inevitably colored his life and music. “The most important thing in your life is what happens at home,” Siffre once said. “It is head and shoulders above everything else.”

To escape Catholicism’s orthodoxy, Siffre found solace in music he discovered in his older brother Kole’s expansive, well-curated vinyl collection: Fats Domino, Charles Mingus, and Little Richard, plus electric bluesman Jimmy Reed, jazz-pop lounge singer Mel Tormé, and the soul-stirring Billie Holiday. Those early influences often bubble up in Siffre’s music, delivered through his complex fretwork, bittersweet lyricism, and a sense of wilted yearning bound in sweet melodies. An obsessive childhood love of Frank Sinatra’s dramatic, heartbroken “One for My Baby (And One More for the Road)” speaks volumes to the wistfulness that arcs through his discography.

By the mid ’60s, Siffre had his mind fixed on becoming a musician. While slogging through an array of day jobs—driving an unlicensed taxi, working as a filing clerk at Reuters, carrying and stacking boxes at a warehouse—he played guitar by night in a trio at Annie’s Club in the Soho district, run by famed jazz artist Annie Ross. Modeling his bluesy style after legendary guitarist Wes Montgomery, the moonlighting allowed Siffre to hone his skills while encountering a series of stars: Mose Allison, Betty Carter, and Joe Williams all passed through the club, setting Siffre’s mind ablaze as he learned from watching his childhood heroes up close. Eventually, he began performing solo at saxophonist Ronnie Scott’s club, where he switched to singing and ditched the electric guitar, preferring the closeness of sound that an acoustic offered him. “For me it always feels as though the amplifier is between me and the guitar,” he explained. “If it’s all fingers then it’s just you.”

That intimacy, drawn from Siffre’s faithful acoustic guitar and his inimitable, high-pitched voice, imbues his music with a comforting glow, as if bathed in the warmth of a snug fireplace. Following his improvised jazz club education, Siffre briefly attended the Eric Gilder School of Music in his early twenties for lessons in harmony, guitar, and singing, where he discovered he’d “merely been hearing” as opposed to listening. At 24, feeling more confident and strapped with several demos and a backing band of his own, he spent three months performing at clubs in Amsterdam to find his footing onstage. When he returned to London in 1969, the demos had made their way around the industry and he was signed for his first album, spurring a prolific run through the beginning of the 1970s that contains some of the decade’s most beguiling music.

Siffre’s first two albums, 1970’s self-titled debut and its follow-up, The Singer and the Song, are rife with pristine, homespun folk-pop like “Bless the Telephone,” a song about waiting for a lover’s call that remains one of Siffre’s most masterful expressions of everyday romance. The records were modest successes, led by the lilting, strings-laden radio hit “Make My Day.” By the time he recorded his third album, Crying Laughing Loving Lying, he had found a sweet spot, chiseling every element of his craft down to a polished, delicate new form.

Crying Laughing Loving Lying is produced and written in its entirety by Siffre. The music runs counter to the flowery, psychedelic English folk of the era, confronting the listener immediately with the stark a cappella song “Saved.” “I am a free man, and my father he was a slave,” he sings, voice soaring into an echo, “I have been broken but my children will be saved.” The song sets the table for the album’s focus on nurturing and being nurtured above any other higher power. “I don’t need religion to tell me what to do,” he affirms. “I know that I should love you.”

An album full of sumptuous acoustic folk, Crying Laughing Loving Lying remains his best work, a fine-wrought synthesis of his lovestruck sound. The jaunty “It Must Be Love” rides a taut ukulele melody during its verses before blooming into a full-hearted valentine: “I need to be near you every night, every day,” he sings, gentle as a down comforter. It’s no wonder the crowdpleaser became the album’s biggest hit, lending itself well to a swaying Top of the Pops performance and reaching No. 14 on the UK charts. But the best song is the knotty, early highlight “Cannock Chase.” Siffre’s guitar gently canters forward while his voice reaches up into a dreamy falsetto to overcome a wave of self-doubt. “I thought my day would never come,” he sings, “Maybe it won’t/But I’ll have fun and I’ll hold tight/’Cause that way it might.” The hopefulness is spurred on by a flurry of horns and strings, rising around him like birdsong.

Siffre’s openness is his greatest strength as a songwriter. He had come out of the closet by the time Crying was released, and was no longer writing oblique lyrics in his ballads. “It occurred to me that I couldn’t do that any more,” he said, instead determined to speak directly about the men he loved, even if listeners didn’t catch on so easily. “I don’t care if there’s another man/I don’t care if there’s three or four,” he sings with a tremble in his throat on the lullaby “Fool Me a Good Night.” “I don’t care because it’s better than the way I was living before.” His queer love songs were written in plain sight, unavoidable to those who listened close enough. (“Give me the simple signs,” he sings on the same song, “Just the ones I want to see.”) The same is true of the sweet, minute-long “Till Forever,” which opens with the image of Siffre peering up from a book to see his lover asleep and wearing his sweater on the sofa, a scene of lived-in romantic bliss that’s restorative in its sincerity. “Put your arms around me, now, after all this time,” Siffre sings in a rousing example of his eye-widening breath control, allowing the phrase to deepen like an exhale.

Siffre’s steady command extends to his uniquely diaristic songs, adding further heft to the ethereal instrumentation and songwriting. “Hotel Room Song” is one of the few tracks about a specific autobiographical moment, based on a TV interview that put Siffre in a sour mood before a concert. The song catches him mid-thought over career doubts, captured against rippling guitar and celesta: “Last night I thought ‘I’ll never ever write another song,’” he sings ponderously, “Last night I decided that all the songs I write are wrong.” It’s a brief self-portrait of a young artist struggling with the demands of an industry he already found himself in spiritual conflict with.

On the title track, another hit single, he finds astonishing beauty in simplicity. Locking into a mesmerizing roundelay, Siffre circles a tranquil guitar melody with warm, multi-tracked vocals, moving through four similar verses that capture a swirl of contradictions with sly ease. “Loving never did me no good no how,” he sings, “That’s why I can’t love you now.” Then he reveals the undercurrent of irony: “Lying never did nobody no good, no how,” he allows, voice fading into the air, “So why am I lying now?” It’s a distillation of his best songwriting impulses, roaming and tightened at once, with sheer joy holding its center.

Crying Laughing Loving Lying reached No. 11 on the UK charts, making it his most successful album and leading to critical acclaim and a wider fanbase. The music on his three follow-up albums, especially 1973’s social justice-minded For the Children and 1975’s funky Remember My Song, continued his trend of crafting precise, absorbing music, now occasionally informed by more explicit political and sociological ideas. Unsurprisingly, audiences weren’t as receptive.

Following the release of 1975’s Happy, Siffre moved to the English countryside to spend time with his lifelong partner and husband, Peter Lloyd, and focus on different pursuits. He was disillusioned by a fickle music industry and the constant demand to write singles resembling past successes. “I went in believing that the music business would be run by—who else?—musicians,” he conceded. Siffre also faced the claustrophobic labeling of his music by his various identities. “Being Black, you were supposed to be ethnic. Being gay, you were supposed to be camp,” he explained. “Then you could be put in a little box.” His work always resisted such markers and Siffre insisted that his music be respected on its own, never abiding by the cult of celebrity around any artist.

During his absence from the spotlight, however, Siffre never stopped writing. He returned to the charts in 1987 when, horrified by a documentary on apartheid in South Africa, he penned the anthemic “(Something Inside) So Strong” as a direct response. While its lyrics vividly condemn racist discrimination, “So Strong” is multifaceted and speaks just as easily to Siffre’s sexuality. “The higher you build your barriers/The taller I become,” go the opening lines, offering a path of self-expression for those who may not have one readily available. Through his music, Siffre has always subverted the ways institutions exert power over people, threading themes of self-empowerment into his easy-listening production with subtle repose. During Pride month in 2020, he released the ballad “(Love Is Love Is Love) Why Isn’t Love Enough?,” a reworking of an older track that speaks to years of living and loving as a queer person.

Though Siffre never became a household name, his influence is wide-reaching. When the ska-punk band Madness covered “It Must Be Love” in 1981, it peaked at No. 4 in the UK and has since become a wedding staple in the country (Siffre is there at the end of the video, grinning and playing a violin as a surprise member of the band). Olivia Newton-John released a version of “Crying Laughing Loving Lying” in 1975, while Kenny Rogers covered “So Strong” and built an entire album around the song only a year after its release, giving it a healthy second wind. As recently as 2014, Kelis recorded a cover of “Bless the Telephone,” adding to the song’s lovelorn pathos with her own faithful spin.

It’s easy to see why so many artists remain besotted by Siffre’s unassuming complexity. His work most prominently pumps through hip-hop’s DNA; it’s Siffre’s funky guitar, reinterpreted from the delirious 1975 two-hander “I Got the…,” that Jay-Z used for “Streets Is Watching” and which Dr. Dre looped in order to launch Eminem’s career on “My Name Is.” (Siffre, unfamiliar with sampling and bothered by Eminem’s lazily homophobic and misogynist lyrics, only approved a clean version of the track at the time.) On “I Wonder,” a beatific track from Kanye West’s 2007 album Graduation, West lifts a passage from Crying’s “My Song” and leaves it largely intact, fully understanding the power of his voice left unadorned. Siffre’s work is so stitched into the pop cultural fabric that, once you start to look, you find his fingerprints everywhere.

Now in his 70s, Siffre is a prolific author and has begun to open up more in interviews on his undersung career with characteristically British modesty—“I’m getting used to being rediscovered,” he joked with a hearty laugh during a 2020 podcast. His entire catalog is rooted in that unswaying sense of self. “I don’t believe in giving the audience what they want,” he said in that early 1972 BBC interview. “I believe in giving them my best and making them like it. You don’t make hit records that way, but you can sleep at night.” A profound sense of dignity courses through Siffre’s entire career, but it effloresced on Crying Laughing Loving Lying, a statement of compassion that hasn’t lost any of its well-worn charms.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.