When she was in high school in Creston, Iowa, Julee Cruise was a popular girl with a host of deep-rooted suburban fears—boys, cars, getting sucked down the bathtub drain—and a secret pastime that even those closest to her never knew about: making prank phone calls. “I’d call people if I was angry at someone and wanted to scare them. Or I’d call and not say anything at all,” she reflected in a 1990 interview. “There’s something kinda voyeuristic about doing something like that.”

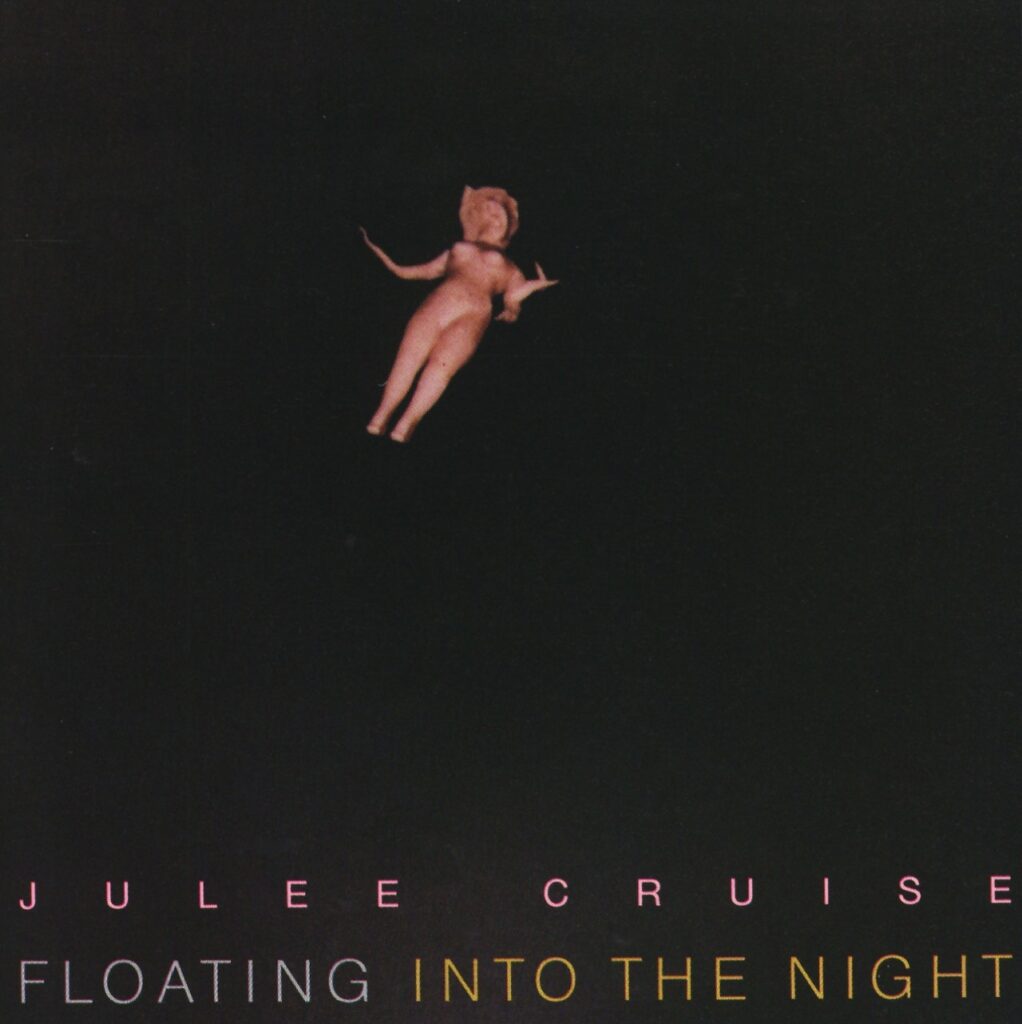

Eventually, Cruise made contact with the world. First in Blue Velvet and most prominently throughout Twin Peaks, she sang the eerie, beautiful songs that reached from the screen and pulled you inside David Lynch’s mind, giving voice to the complex web of emotions that kept his characters suspended in time. Her debut record, 1989’s Floating Into the Night, is the latest from the Lynch universe to receive a welcome vinyl reissue from Brooklyn label Sacred Bones. And while the lyrics were written by Lynch with music composed by his right-hand-man Angelo Badalamenti, and most of the songs will forever be associated with his work, Cruise’s album stands proudly on its own.

Over the past three decades, Floating Into the Night has remained one of the benchmarks that all dream-pop artists are measured against. It set the standard for several reasons. One, of course, is that its songs were paired with some of the most unforgettable, vividly rendered dream sequences ever caught on camera: from the foggy, rainy vistas of Twin Peaks to its dusky barrooms, sepia-toned living rooms, and demonic purgatories. If you have any relationship to the images these songs accompanied, then just hearing the opening baritone-guitar pulses of “Falling” or the wheezing gramophone band of “Floating” can elicit an intense rush of emotions.

Even stripped of this context, Floating Into the Night captured something important about dreams that plenty of other artists in the genre have ignored. Like most dream-pop records, it has the ability to wash over you, misty and serene, with a late-’80s synth gloss that made one of Cruise’s friends dismiss it as “white wine Muzak.” But Cruise and her collaborators also had the ability to shake you awake, to twist an image that should be pretty into something broken and grotesque. There are obvious examples: the nightmarish orchestral stabs that interrupt the whispered revery of “Into the Night,” the hellish fade-in crescendo of “I Remember,” or the disorienting drone and piano solo in “I Float Alone.” Lynch and Badalamenti shared a penchant for long, simmering builds and sudden cuts, dives into sentimentality harshened by pure horror. Their music together accomplishes a similar effect, never allowing you to feel fully at ease.

Cruise was a natural collaborator, able to skate along gracefully without stumbling around these turns. It’s hard to think of another singer who could find so much space and resonance in words like “dark” or “alone,” and by subduing her musical-theater belt into a curling wisp of smoke, her mezzo-soprano takes on a haunted, slow-motion quality: If you close your eyes, you can almost see each word forming as she sings them before dissolving into blackness.

The initial inspiration for “Mysteries of Love,” Cruise’s first collaboration with Lynch and Badalamenti, was This Mortal Coil’s “Song to the Siren,” and you can hear what they admired in the recording: its sparse alien landscape, and the sense of longing in Elizabeth Fraser’s crystal-clear voice cutting through the mix. But they quickly evolved into their own sound, evoking a less heavenly tableau with more smoke in the air. Within this setting, Cruise favored a hushed delivery in layers and layers of multi-tracked harmony and unison vocals, like Christmas carols by ghostly choirs on deserted streets. (“This will be a very expensive tour because Julee will have to hire nine backup singers,” Lynch jokes in a priceless clip from the recording sessions.)

Both Cruise and Lynch spoke of America in the 1950s as an enduring influence, and the songwriting spans aspirational jazz standards like “The World Spins”—a recording that, no matter how you listen, seem to play on a format that must be handled gently so as not to shatter—to early rock’n’roll throwbacks like “Rockin’ Back Inside My Heart.” In the latter, Cruise remembered Lynch instructing the sax player to conjure “big chunks of plastic” from his instrument, suggesting the visceral, physical thrill they still found in music from this era.

Even with these specific reference points, there is no true precedent for Floating Into the Night, and its greatest asset remains its timelessness. Describing her inspiration, Cruise pinpointed the feeling of paranoia that accompanies any surge of joy or new love. “There’s always that voice that says, ‘It’s going to go away,’” she explained. “That voice can be very disturbing and destructive, and that voice is talking all through the album.” If Lynch’s work remains a confounding acquired taste for some, then Floating Into the Night is a record that anyone can at least understand. It is the sound of a burgeoning crush accompanied by the quickening realization of their power to hurt you; it is your hometown at night, with a familiar stillness so quiet it can keep you awake; it is the voice on the other line, distant and mysterious, but close enough so you can hear every breath.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.