Elton John has said that Honky Château did for him what Revolver did for the Beatles: It pried open the gilded gates, lifting him “onto a higher plane” as an artist. In 1972, when Honky Château went to No. 1, ending the Rolling Stones’ five-week reign with Exile on Main St., Elton was still a rascal. He had just turned 25 with seven records to his name, and he had yet to ascend into bona fide rockstardom. He was still small-time enough to be coerced to record outside of England to cut down on costs, his day could still be ruined if a hot American album arrived at an import shop a day late, and he still wore somewhat flat shoes on stage.

In its quaint intimacy and drama, Honky Château was a signpost of Elton’s imminent success, and four back-to-back classic records were waiting in the wings. The title honors Château d’Hérouville, the French countryside studio where it was recorded, the same one in which Vincent Van Gogh painted and Frederic Chopin had a mad love affair. Many fellow ’70s musicians, from Brian Eno to David Bowie, claimed the Château hosts centuries’ worth of something supernatural, with some going so far as to suggest that each record made there—think T. Rex’s “The Slider” and Bowie’s “Pin Ups”—holds a certain mystic quality.

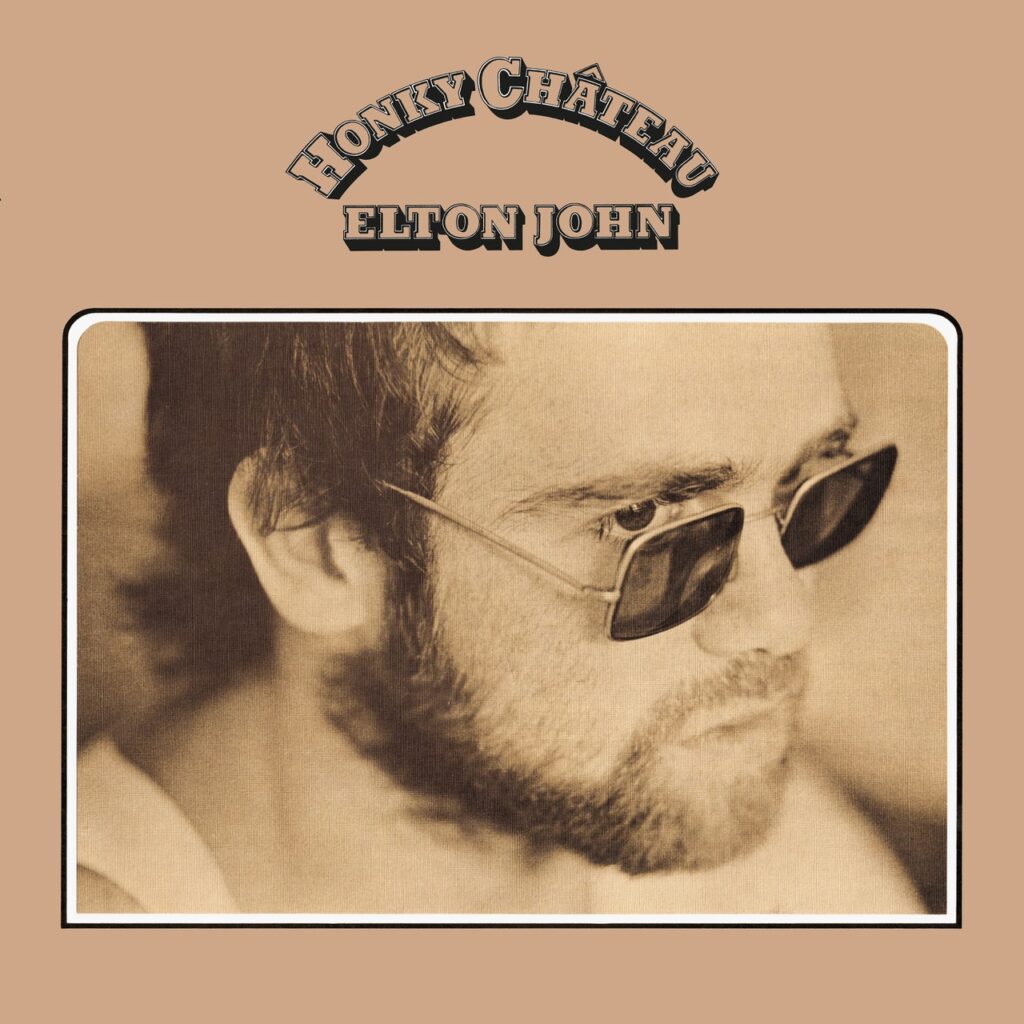

Elton’s signature whimsy cloaks Honky Château like mist, so palpable that it almost confirms that fabled spirits must have come to his aid. The 50th-anniversary reissue continues to phantomize the soul-stirring and profound sentiments first cast in 1972, while remaining a tender portrait of Elton pre-rhinestones, as a fledgling celebrity. It boasts the option of a double LP or double CD, the latter featuring eight live recordings from Honky Château’s inaugural performance at London’s Royal Festival Hall in addition to bare outtakes from the Château, as well as a 40-page booklet. In these early recordings, Elton’s passion and dedication pleads to be heard. Whether nitpicking intros almost to the point of nausea or infusing vitality into each syllable like a mad scientist, a young Elton is constantly straining towards vein-popping perfection. And he’ll stop at nothing until he gets it.

“Rocket Man,” a smash hit that was finished on his first day at the Château, sent Elton spaceward, much to Bowie’s chagrin. The common thread of “man in space” drew frequent comparisons, including from the Starman himself, who once agreed with a radio host who implied that Elton was riding his coattails. Longtime collaborator Bernie Taupin said in 2016 that the true inspiration for “Rocket Man” came from a 1951 short story by Ray Bradbury, about an astronaut father who leaves his wife and son for months on end to patrol planets and sweep stardust. Elton’s version of the tale soars on an electric slide guitar that melds the ordinary with the cosmic, defining how quietly devastating it is to have something you must leave behind.

Honky Château wears many hats, some more crooked than others. The springy step of songs like “Honky Cat” and the morbidly satirical “I Think I’m Going To Kill Myself” are split by the cozy love song “Mellow.” The record then momentarily darts to two consecutive ballads that—despite pure intentions—miss the mark: the humanitarian anthem “Salvation” and the freedom-seeking “Slave” (neither of which Elton has performed since the 1970s). Though the attempt at activism seems sincere, it’s an odd diversion from the otherwise whimsical material on Honky Château. The pursed-lip, head-bobbing dueling piano and guitar groove of “Susie (Dramas)” is a more worthy overlooked gem. Elton’s tough-guy piano riff could strongarm any rival instrument into submission, save for guitarist Davey Johnstone’s street-smart, tomcat electric.

One track on Honky Château stands alone, without fanfare or hit-making fantasies of lonely rocketeers. Not unlike the rose of its “Spanish Harlem” inspiration, “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters” gracefully slips out of the sullied fog that blankets New York City streets at dawn. Drawing from Taupin’s disappointing experience as a first-time visitor—arriving with starry eyes only to have the illusion shattered by a gunshot outside of his hotel room window—Elton sings of a silent observer who wades through disillusionment as reality bears down on him.

Though wonderland ideals of the big city fall short, the innocence of Johnstone’s childlike mandolin promises something better. As the track pieces together a mosaic of the madness of the “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters” that parade past him, lucky to be doomed, Elton insists, “I thank the Lord for the people I have found.” It is a message of unshakable resilience, as when the gunsmoke clears, the observer is forced to toss city hopes aside and search for beauty elsewhere: in his fellow man. This is not without conscious effort and the help of a certain cosmic grace (he does not sing, “I thank the Lord for the people I have met,” after all), but as the song draws to a close, the lasting truth of shared humanity is resplendent in spite of adversity.

On Honky Château, Elton nurtures his budding legacy as he navigates out of his youth. From his time standing wide-eyed and naive at the edge of recognition to his time spent facedown in the gutter of disenchantment, one nameless, cockeyed hope of “making it” still tantalizes him, and will eventually carry him into lasting eminence. Much like what haunts the walls of Château d’Hérouville, the charm of Honky Château lingers in low lamplight, crystallizing Elton’s last anticipative, moonshot glance towards stardom before it swallows him whole.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.