When Elliott Smith sat down to lunch with Lenny Waronker, he hardly spoke a word for 40 minutes. The fact that he’d even been coaxed into a meeting with the co-CEO of DreamWorks—the glittery new entertainment venture founded by Jeffrey Katzenberg, David Geffen, and Steven Spielberg—was a testament both to Smith’s own quietly undeniable ambition and his codependent relationship with his then-manager, Margaret Mittleman, who had coaxed and cajoled him into place. Smith was the kind of guy who had to be ordered sternly to go back out in front of a crowd of 50 when his stage fright overwhelmed him. Now he was at a white-tablecloth power lunch with the guy who signed Randy Newman, and things were going poorly.

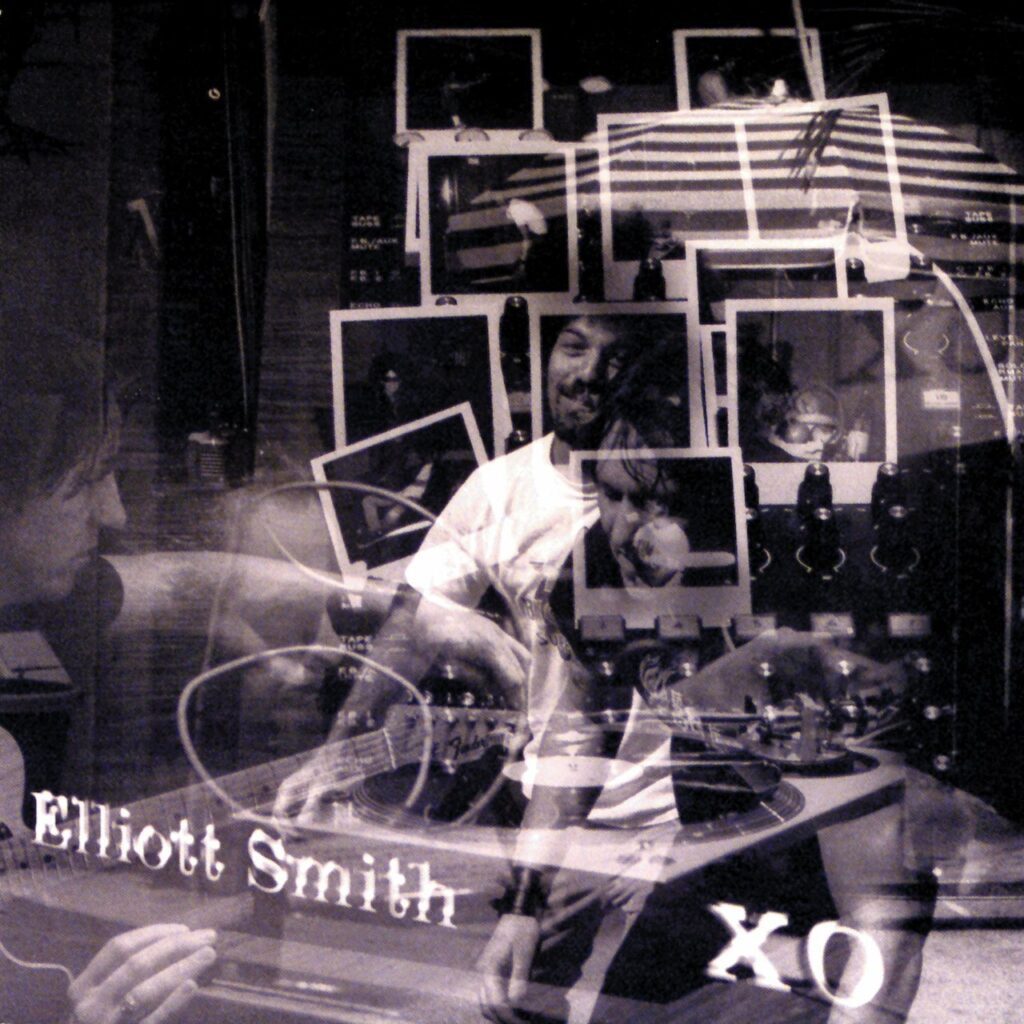

Waronker had handled some difficult singer-songwriter types in his day, but with the painfully shy Smith, he found himself at a loss. Finally, he pointed to the orchestration primer he noticed Smith clutching to his chest like a child’s security blanket and asked him about it. The tension finally broke; Smith began regaling Waronker with his grand visions for what would become XO. For his next record, Smith confided, he wanted to use an orchestra.

Up until then, Smith was known for playing music so quiet it almost died away before it reached your ears. He made most of his first three albums in friends and loved ones’ bedrooms, and it was his 1993 debut Roman Candle, which he recorded in then-girlfriend JJ Gonson’s basement by pressing his guitar strings against a low-quality microphone, that transfixed Luke Wood, DreamWorks’ A&R. The thought of Smith singing over a full orchestra might’ve seemed as unlikely in that moment as collaborating with Metallica.

But Elliott Smith had already lived several musical lives before he became “Elliott Smith.” Starting as a freshman at Hampshire College, he co-fronted the distortion-soaked alternative rock band Heatmiser, striking lip-biting guitar-god poses and riling up beery crowds at punk clubs. As a high schooler in Portland, he’d written and recorded multiple album-length art-rock opuses with his music-nerd friends, testifying to his childhood love of Rush and Yes. It was only when he set out to make his solo debut that he tested out a whisper—maybe to see how it felt, maybe because he sensed that was his truest register, or maybe because he’d already spent years trying to snarl like Elvis Costello. This was the sound that had started winning him converts—fanatical ones—but he had other, bigger sounds in his head. Now that he’d just become labelmates with George Michael and John Williams, it was time to try them out.

XO captures Smith on the cusp of his biggest transformation. He became famous during its recording, not after—a strange state of affairs owing to the fact that he’d given a few of his songs to the indie filmmaker Gus Van Sant, who used them in a movie called Good Will Hunting. That movie went on to gross $138 million, making stars of everyone involved, and then “Miss Misery” was nominated for an Oscar. Suddenly, Elliott Smith was fielding phone calls from People Magazine reporters in between sessions where he was laying down drum, bass, piano, and guitar tracks. He was scheduling back-to-back interview blocks in the studio lounge as he tracked vocals. His compositional ambitions were flowering. His career was exploding. He was at the center of it. Somehow, it didn’t crush him.

The most remarkable thing about Smith’s career is the degree to which pressure—even the overwhelming kind, which might be expected to break a soul as sensitive as his—never once stopped the flow of his songwriting. “Songs would just come up,” marveled Rob Schnapf, the producer he worked with on both Either/Or and XO, of Smith’s writing process. “Maybe they weren’t necessarily written in the studio, but they’d be written while we’re making the record.” The songs that went on to comprise XO seemed to pour in from every corner imaginable, and no matter what else was happening in his life—suicidal ideation, addiction, paranoia, finding himself backstage at the Oscars being comforted by Celine Dion—he never once seemed to struggle with writer’s block. In an interview with The New Yorker, Neil Gust, his bandmate in Heatmiser, struggled to understand his friend’s prodigious genius: “He got to a place where it just lined up. He just couldn’t not nail it.” Luke Wood remembers how Smith would write “four or five different sets of lyrics” for each song, and Smith’s rarities are littered with examples. Perhaps he’d spent so long cultivating that channel that it stayed open, or perhaps because he wouldn’t know how to shut it off if he tried, songs flowed through him from the first moment he tried writing one in middle school to the end of his life.

Most people look back at XO, his DreamWorks debut, as his big break, but really, it was just his next logical step. Before XO, he’d suppressed his instincts towards grander gestures, maybe to strike a contrast with his Heatmiser music or from some allegiance to punk rock purity. Maybe he associated those gestures with his youthful prog-rock misadventures, which embarrassed him. He’d allowed a few bigger sounds to seep in at the edges on 1997’s Either/Or, like the crashing rock guitars on “Cupid’s Trick,” and they hadn’t spoiled the mood. “We could have blown it up more, but he wasn’t ready to do it just yet,” producer Rob Schnapf remembered. Now, armed with his orchestration book and Waronker’s blessing, Smith stepped into the studio where both Exile on Main Street and Led Zeppelin IV had been recorded and went for broke.

The songs were still recognizably his—you could strip them back to just acoustic guitar, as he often did live, and they fit neatly alongside his earlier material. But glorious new sounds welled up everywhere: the Mellotron that turned the chorus of “Bottle Up and Explode!” sunset-pink; the bass saxophone honking its way through on “A Question Mark”; the George Harrison-style acoustic slide guitar on “Oh Well, OK” or the “Getting Better” guitar chimes of “Baby Britain.” On album opener “Sweet Adeline,” he even indulged in some Dorothy-enters-Oz playfulness—for a full minute and a half, the song resembles a slightly cleaner, crisper, take on the hyper-intimate folk of his previous records. But then, just as the lyrics land on the title phrase, Smith’s voice reaches for a new, louder register, and then—what’s this?—a full band crashes in, complete with huge, pounding “When the Levee Breaks”-style John Bonham drum hits and multi-tracked vocal harmonies, all of them recognizably Smith. His songs had been a lot of things—lucid, tender, angry, brilliantly constructed—but they had never before been showy.

Smith moved from instrument to instrument in the studio with the laser focus of someone possessed, testing songs out songs in different registers, keys, and arrangements. On day one of recording, he demoed and finalized a sickly, twirling lullaby in 3/4 time that he just called “Waltz #1.” He’d written it after listening to Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” on mushrooms for 18 straight hours. Foggy, staggering, and fragile, the song never breaks from its simple rhythm but seems to exist in a world outside meter. There might be no more naked moment in his catalog than the tipsy stagger up the Db-major scale to his pleading line, “What was I supposed to say?”

The other, more famous song on XO with the word “Waltz” in its title also explored childlike feelings of fear and helplessness. Something about 3/4 time seemed to stir primal feelings in Smith, and he returned to the time signature whenever he found himself staring into the dark pool that waited in his subconscious memories of childhood in Cedar Hill, Texas. Maybe it was a method of self-soothing, a sort of musical EMDR that allowed him to revisit the childhood ghosts that never entirely left him. But “Waltz #2,” Smith’s lead single, deals rather conspicuously with the troubled dynamic that Smith observed between his stepfather, Charlie Welch, and his mother, Bunny.

The song is set in a karaoke bar, the characters a man and wife taking turns on the stage. The woman selects “Cathy’s Clown” (”Don’tcha think it’s kinda sad/That you’re treating me so bad?”), while the man returns the message, with a vengeance, choosing “You’re No Good.” “Waltz #2” is a song about people singing subtext-loaded songs to each other. It is also, itself, loaded with subtext. Smith wasn’t typically eager to encourage biographical readings of his songs, but in live performances he seemed to have no compunction about making this subtext clear, subbing the sign-off lyric “XO mom” with the plainly sung “I love you, mom.” For this song, at least, there was no alternate reading.

Smith’s relationship with his stepfather was always fraught with uncertainties. Welch wrote Smith more than one pained letter of apology after Smith left Texas for his father’s home in Portland halfway through his freshman year in high school. Later, Smith wrote a sort of acknowledgment and apologia of his own, another waltz-timed number called “Flowers for Charlie” that borrowed the melody from John Lennon’s “Happy Xmas (The War Is Over).” Whatever else Smith’s childhood meant, XO was a moment for him to dredge up bits of his past, holding them up to the light of Sunset Studios to see what they might yield.

It was by way of this method that he came to revisit one of those old songs from his high-school band days, those formerly mortifying years of extended whammy-bar solos and mullets. “Everybody Cares, Everybody Understands” began life as a tough, snarling rocker called “Catholic,” when Smith and his friends were recording under the name Harum Scarum. Now, it was “Everybody Cares, Everybody Understands,” and again, the target of the song was unusually direct: Smith wrote it as a rebuke of the friends who had staged his 1997 intervention and insisted he go to rehab. The song climaxes with that string orchestra arrangement Smith had dreamed of. Smith arranged it himself on a MIDI keyboard as a reference to hand to the professional arrangers, Shelly Berg and Tom Halm, only to revert to his original when he didn’t like the results. As the strings surge into the foreground, the song enters a phantasmagorical space, one where new instruments seem to be sprouting off the song’s walls like vines. Smith had grown up idolizing the Beatles; now, he was orchestrating his very own “A Day in the Life” within a song written with one group of close friends, rewritten to chastise another.

Dreams and grievances, biography and metaphor, truth and fiction—it all swirled together in Smith’s music until every throwaway line seemed like a secret. Smith fans were spooked into lifelong identification because of the purity of that voice, its unmistakable sadness, its seeming simplicity. But the deeper you peered into Smith’s music the more elusive and diaphanous the portrait of “Elliott Smith” became. Behind “Elliott” was, always and forever, Steven Paul Smith, the guy behind the guy behind the guy who had been working out his childhood songwriting visions for a lifetime and arrived at a point in which his ambitions and his talent synced up in one tall, clean line. The “Elliott Smith” of Smith’s solo records was not a person; it was a project. And XO was a testament to how far that project could go.

The breadth and depth of XO astonished even his benefactors. “The clarity and continuity of [his] thought is amazing,” said Wood. “He can take a metaphor…and sing about it for three minutes and never leave.” Waronker himself said that Smith was “as good as it gets when you’re talking about layers within lyrics.” On the stunning closing chorale, “I Didn’t Understand,” Smith sighs the line: “My feelings never change a bit, I always feel like shit/I don’t know why, I guess that I just do.” It sounds like a pure depiction of depression, in all its weariness and ingrained fatalism. It sounds, as it always does, like confession, like the truth that remained after exhaustion had burned away all artifice.

And yet behind even this song, you can find ghosts of previous versions, with implications of different meanings, dancing behind it. Early versions—on piano, rather than poised against Smith’s stacked vocal harmonies—reveal alternate lyrics: “My feelings never changed a bit/I’m waiting to get over it, but I know what it is I have to do.” The shifting tense of “changed” to “change”; the gap between “I know what it is I have to do” and “I don’t know why, I guess that I just do”—somewhere in the elongating shadow space between them, Elliott Smith the draftsman, the songwriter, the notoriously shy performer who never brought his eyes up from a spot a few feet away on the floor, seems to flick his gaze up to meet you head-on. There were no confessions on Elliott Smith records, but there were moments, like this, where he put every single nerve and sinew of his being on display.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.