Warwick. It was a misprint on the label of her first single. In 1962, the 22-year-old Dionne Warrick was on her way to becoming one of the greatest singers in American history. But her record label was treating her as another cog in the machine, just as the industry treated most artists, especially those who were Black. Scepter Records promised they’d correct the error for her next single, but that one said Warwick, too. Perhaps it was because “Don’t Make Me Over,” the single’s B-side, had been a breakout hit. Listeners now recognized that second w, which meant there was money riding on it. Dionne Warwick she remained.

Burt Bacharach’s name was also misspelled on that first single. It said Bert, which was his father’s name. (His mother gave him the u because she felt, for reasons lost to time, that it would protect him from the teasing his dad had apparently endured as a child.) By that point, the songwriter and his lyricist partner, Hal David, had a track record as hitmakers, which gave Bacharach a certain sway among executive types. Also, he was white. The e never showed up on a label again.

At first blush, “Don’t Make Me Over” may seem typical of the girl-group sound that was all the rage in the early ’60s, with a swooning string section and a chorus of female background singers punctuating Warwick’s lines. But its musical underpinnings are idiosyncratic: The verses pivot on a chord that most songwriters wouldn’t go near, and the vocal phrases are five bars long rather than the standard four, with a time signature change thrown in for good measure. Warwick makes an extraordinarily difficult melody sound intuitive and relaxed, a trick that could only come through her combination of innate talent and rigorous discipline. The arrangement is ornate but not stuffy, revealing a delightful new instrumental voice with practically every bar. Bacharach’s contemporary Phil Spector liked to compare his productions to little symphonies, but this was a lot closer to the real deal. Spector draped simple pop compositions in lushly symphonic instrumentation; Bacharach’s songs are ingenious in their bones, whether performed by an orchestra or a soloist.

Coincidentally, “Don’t Make Me Over” arrived in stores a few months before the publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique helped to kickstart feminism’s second wave. David’s lyrics, written at a time when pop songs were far more likely to uphold gender hierarchies than upend them, were a plea from a woman to a man to stop trying to control her. In the bridge, it becomes more like a demand: “Accept me for what I am!/Accept me for the things that I do!” The rhythm and harmony simplify, and Warwick starts to really belt, moving from her restrained early delivery into one more clearly inflected with her lifelong background as a gospel singer. It was the world’s introduction to her one-of-a-kind voice, with a dynamic range encompassing utmost delicacy on one end and walloping force on the other, her deep sensitivity to a song’s emotional contour matched by her virtuosic technical control. The song is a lesson in music theory and performance as well as a shot straight to the heart. When the intricacy of the verses gives way to the feeling of the bridge, it’s like exiting a series of switchbacks and taking in the view from the mountaintop.

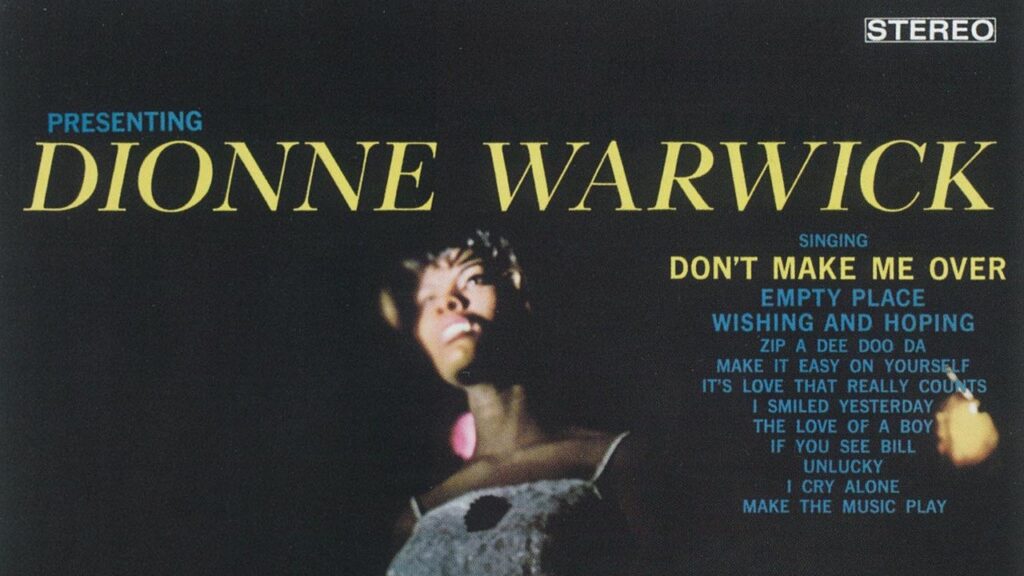

Presenting Dionne Warwick, her first album, released the following year, is an imperfect lens through which to examine her artistry. But then so is her second album, and her third, and any other album after that. No one album tells the story in full, in part because Warwick’s career has been so long and fruitful—56 singles in the Billboard Hot 100 across three decades, with dozens more on the R&B and adult contemporary charts—and in part because she rose to fame just before the album took its place as pop’s dominant format in the commercial market and the popular imagination.

Like most pop and R&B labels operating at the time, Scepter was primarily concerned with hit singles. The album was an ancillary product, a different format for selling songs that had already proven themselves as hits. 1963 was the twilight of the Brill Building era, a sort of nether zone in pop history, bookended roughly on one side by the drafting of Elvis Presley into the U.S. Army in 1958 and on the other by the arrival of the Beatles in America in 1964. As Ken Emerson puts it in Always Magic in the Air, his indispensable history of the era, it was a time when the industry “routinized the creation and production of rock’n’roll,” with the help of professional songwriters like Bacharach and David, many of whom had offices in the midtown Manhattan building that gives the period its name.

Rock’s first boom, in the mid-’50s, had dramatically expanded the market for recorded music, but it hadn’t been planned from the top down, having arisen from upstart labels like Memphis’ Sun Records rather than corporate offices in New York or Los Angeles. Its early stars were unpredictable and sometimes unruly personalities. By the decade’s end, Elvis was serving in Germany, and other key performers were either dead (Buddy Holly) or embroiled in controversy (Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis). The industry, in order to control the money pouring in from the newfound teen market, established a model in which performers were relatively interchangeable, bound by contracts that enforced the label’s authority over their output. One particularly egregious case involved the pioneering Black vocal group the Drifters, whose members were swapped in and out at will by a manager who owned the rights to the group’s name, and who paid them in an arrangement that the Brill Building songwriter Mike Stoller, in There’s Always Magic in the Air, likened to slave labor.

Warwick and Bacharach were odd fits for the rock’n’roll assembly line. Both were conservatory-trained: she a young gospel devotee who could sing opera, jazz, or any other style if she wanted; he a 30-something aesthete and tinkerer who spent his adolescence sneaking into Manhattan bebop clubs and once wrote that he might enjoy Bill Haley and His Comets more if they used a few major-seventh chords. The music they made together with David sounds only occasionally like R&B, and almost never like rock. Suffused with jazz and classical harmony, set to rhythms influenced by the Brazilian music that Bacharach encountered in his years as a touring conductor, and with Warwick’s vocals emphasizing clarity and precision as much as fervor and abandon, it’s not the first thing a DJ might reach for to set the sock hop on fire. It is adult music, barely masquerading as kid stuff. These three were not the only people making personal and unconventional music within the strictures of the Brill Building model, which encouraged frivolity and homogeneity, but theirs went the furthest out from the expected forms.

The brass at Scepter apparently had their doubts that the singles the trio created had any potential as hits, and it’s hard to blame them for that. “This Empty Place,” Presenting Dionne Warwick’s opener and Warwick’s second single, spends its verses flipping between minor and major versions of the same chord, a strange move in rock’n’roll or any other genre. But its complexity, like that of “Don’t Make Me Over,” is never ostentatious. Unusual harmonies and meters are a means to an end: heightening the feeling in a particular lyric, giving a melody more space to breathe, bringing the phrasing of a vocal line more closely to the natural patterns of speech. The music, despite its difficulty to perform, is unfailingly inviting and emotionally present. Warwick and her collaborators used their extraordinary skills to better reach listeners, not to talk past them or show off.

As the chords ascend through the chorus of “This Empty Place,” so does the searing heat of Warwick’s vocal, delivering a David lyric about the aftermath of a breakup. Then, suddenly, the backing singers drop out, the rhythm section cools off, and she’s all alone to sing the kicker: “Now there’s not a star left in the sky/And if you don’t come back to me I’ll die,” with a flippant melodic curlicue on the last word. Another singer might read that couplet as if it were a literal matter of life and death. From Warwick, it comes across more like a taunt. Her breakneck shift between emotional registers provides a thrill that no amount of tinkering with harmonies could approach on its own.

Given the realities of the era’s music industry, it is understandable that Warwick approached her early dealings with Scepter and Bacharach-David with some caution. In her telling, “Don’t Make Me Over” is a direct result of that tension. Bacharach, after encountering Warwick as a background singer on a session for the Drifters, first hired her to provide vocals on the demo recordings he made to shop his songs around to labels. Impressed by her musical ability and easy charisma, he and David soon encouraged her to pursue a solo career, with the two of them writing and producing. She was still a conservatory student, commuting to New York from her Connecticut campus for session work. In order to convince her mother that the shot at stardom wouldn’t interfere with her studies, she told the songwriters that she could only record on weekends.

Warwick claims that Bacharach and David had promised her “Make It Easy on Yourself,” a song that she particularly loved and had recorded as a demo for her first single. She was on her way to a session with the pair when she heard another singer’s rendition of “Make It Easy on Yourself” on the radio. When she arrived, she says, she admonished them not to go behind her back, or tamper with her vision of herself as an artist. “I felt Burt and Hal had given my songs away and they felt they hadn’t and that maybe I was being a bit unreasonable,” she said in 1997. “Well, one word led to another… and I finally said, ‘Don’t make me over, man!’ and I walked out.”

In Bacharach’s version, he and David came up with “Don’t Make Me Over” without that bit of verbal inspiration from Warwick. There was never any promise about “Make It Easy on Yourself,” he claims in his 2013 memoir, and the subsequent shouting match never happened. His insistence on writing Warwick out of the song’s creation, given its content and the historical context, is ironic.

Also ironic: On Presenting Dionne Warwick’s tracklist, alongside “Don’t Make Me Over,” a song with a message of women’s strength and agency rarely heard in pop music at the time, sits “Wishin’ and Hopin’” a sweet little ditty about how women can only find real love through subservience to their men. Musically, it is among the album’s most distinctive tracks, with a melody like a multicolored bouncy ball. But the words: “Show him that you care just for him/Do the things he likes to do/Wear your hair just for him,” and so on.

It’s possible that the lyric of “Wishin’ and Hopin’” had less to do with David’s latent misogyny (and, for that matter, “Don’t Make Me Over” with his feminist streak) than with the mechanics of the Brill Building model, in which songs were not expected to be expressions of deeply held individual sentiment so much as practical attempts to resonate with the attitudes and desires of the listening public. Women’s independence was in the air in 1963, and so was the reaction against it. David wrote songs about both. “Wishin’ and Hopin’” didn’t gain any chart foothold when it was released as the B-side to “This Empty Place,” but a nearly identical cover version by Dusty Springfield hit the Top 10 when it came out a year later. (Incidentally, the detachment from the personal perspective—along with the fact that the Brill Building was full of men writing for women performers and vice versa—also meant that their lyrics were broadly interpretable. There are many versions of Bacharach-David songs that have been gender-flipped from their original recordings, including a charming rendition of “Wishin’” by British Invasion also-rans the Merseybeats, in which frontman Billy Kinsley advises his fellow guys to wear their hair in just the way their girls like.)

Outside of the singles, much of the material on Presenting consists of Bacharach-David songs that Warwick had previously cut as demo recordings for other artists. Why spend time and money on making new album tracks when they could just repurpose these recordings they already had sitting around, tack on the hits, and call it a day? But the ghostly minimalism of the demos doesn’t take much away from Presenting as a listening experience. Often, it enhances it, providing contrast to the grandeur of the singles and reflecting the often lovelorn mood of David’s lyrics. Bacharach was meticulous even with these preliminary takes, a habit he picked up in hopes of conveying ideas about instrumentation to a producer when he was greener in the industry and did not yet have license to oversee the recording sessions for his songs. Though the arrangements lack the elaborate orchestration of his final versions, they make up for it in small-scale ingenuity. A backing singer might deliver a wordless countermelody that Bacharach intended ultimately for a string section. Because the studio where he made demos had a good-sounding reverb unit, he slathered everything in lonely, atmospheric echo.

In most cases, Warwick’s performances are superior to those of the artists for whom she was ostensibly providing a throwaway guide vocal. Take “Make It Easy on Yourself,” the song whose release ignited the argument that led to “Don’t Make Me Over.” With the nuanced view of relationships that characterizes David’s best work, its narrator addresses a lover who has begun to stray, imploring them to make a clean break so that they can at least enjoy their own life while the narrator deals with the heartbreak. The first publicly released version, the one that Warwick heard on the radio that day, was performed by Jerry Butler, whose reading is expressive bordering on maudlin, flattening the layered sentiment of the words until self-pity is the only legible feeling. Warwick’s original demo, which appears near the end of Presenting, holds back from emoting, drawing out a certain matter-of-factness in the melody and lyric, and preserving the protagonist’s dignity in the process.

Three newly recorded songs by writers other than Bacharach-David round out the tracklist. The most powerful of these, by far, is Warwick’s rendition of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.” There’s no record I can find of whose decision it was to include it on the album, or of Warwick’s feelings about having recorded it. I imagine they are complicated. Taken from the soundtrack to a Disney film about the Reconstruction-era South so prejudiced and ahistorical it was the target of picketing even upon its release in 1946, and based on a 19th-century minstrel song whose lyrics mocked the freedom of formerly enslaved Black people, its very existence as a piece of music is inextricable from abject racism. And yet Warwick’s delivery is joyful, electrifying, proud, alternating stylish insouciance with unbridled exuberance. Whether or not she intended it as such, it takes on the character of sly rebellion, of using the oppressor’s own clumsy weapons against him. When she sings “Plenty of sunshine coming my way,” you can practically hear the smile on her face. It sounds like protest music.

When “This Empty Place” was issued as a single in Europe, it featured an image of a white woman on the cover. “Wishin’ and Hopin’” is one of multiple songs first recorded by Warwick and later released in a near-identical cover version by a white artist that charted higher than her original. On her first tour, which took her through the American South, she faced racial harassment the likes of which she had never imagined as a kid in New Jersey, growing up on a block she likes to compare to the United Nations for all its commingled ethnicities. The backing band was used to playing straight R&B, and had difficulty performing the complicated changes in Warwick’s music. Southern Black audiences didn’t always like it at first either. She took to opening her sets with Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say,” which helped to win them over. Sometimes, she changed one of Charles’ lyrics to “Tell your mama, tell your pa/We’re gonna integrate Arkansas.” Audiences liked that, but the cops didn’t.

Warwick was not the first Black artist whose music was played on both Black and white radio stations, but she found a level of success among pop audiences that was still rare in the ’60s. As her star grew, she began appearing on television programs like Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, which, she writes in her memoir, “let everybody across America know that I was African American.” “Ironically,” she continues, “my crossover success in pop prompted something that came as a big surprise: the decline of airplay for my records on African American radio. In fact, when I asked one of New York’s premier jocks, Rocky G…why he was not playing my records on his show, he told me I was ‘too white.’” The racial dynamics at play in that sentiment are almost too complicated to untangle, especially considering that the radical intricacy of Warwick’s music—the element that most obviously set it apart from the more straightforward R&B records Rocky G would have been playing—was drawn in large part from Bacharach’s love of Black music like bebop.

For nearly a decade after Presenting, Warwick was Bacharach and David’s premiere artist, to whom they gave their most exciting material; and they were her exclusive producers and primary writers. There was still tension between them: In the early 1970s, when Bacharach and David broke up their professional partnership and ceased working with Warwick, she sued them for breach of contract, launching a legal battle that itself lasted for nearly a decade. In the various accounts of their history, there are stories of Bacharach asking Warwick to record dozens of takes, and then deciding that the second one had been perfect all along; or of him pushing her to record a song she didn’t like (the spectacular “Do You Know the Way to San Jose?”), and her crying “all the way to the bank” when it became a hit. In Warwick’s memoir, she refers to David as “the levelheaded one of the trio,” without elaborating on what about Bacharach’s or her own behavior would earn the lyricist that title by comparison.

On the whole, it seems that they loved each other. Bacharach credits Warwick with showing him, through her boundless vocal ability, how much more was possible in songwriting than he’d understood before he met her: “She can go that high, and she can sing that low. She is that flexible. She can sing that strong and that loud, and be delicate and soft too…The more I was exposed to that musically, the more chances, the more risks, I could take.” Warwick writes effusively in her memoir about the beauty and challenge of Bacharach’s compositions, and about Bacharach the man. It’s easy to see why all three collaborators bonded, and why they clashed. David would spend hours agonizing over the placement of a single syllable, Bacharach would wake in the middle of the night in a panic about the mic placement at that day’s session, Warwick would show up at concerts by artists she admired (Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr., Frank Sinatra), sit in the back, and take notes on their performances. All three were nearly fanatical in their pursuit of excellence, and all three had their own ideas about how it might be achieved.

Warwick worked with other writers, and Bacharach-David with other performers, but their collaboration brought out the best in all of them. Bacharach and David supplied Warwick with material worthy of her ability as a singer, and Warwick gave that material humor, style, and human stakes through her performances, elevating it beyond pure elegance of craft into a deeper and more mysterious realm. They may have seen each other as equals, but the industry didn’t, at least not at the time of Presenting: Bacharach got to keep his name, and Warwick got stuck with the w. Inevitably, the friction of these racial, gender, and professional hierarchies left its imprint on the album. It’s there in the spectral quality of those demo recordings, in the tracklist’s inclusion of songs whose lyrics seem to actively belittle Warwick as a woman and a Black person, and maybe even in the way she delivers the bridge of “Don’t Make Me Over,” directing some of her electric defiance at the two men who wrote it for her.

Fortunately for us, Warwick was too big a talent and a personality for the pop music machine to repress. In a recent documentary on Warwick, Bacharach laughs as he recalls a time when, after he’d badgered her to stop smoking cigarettes in the studio, she showed up to a session in a T-shirt with the words “Don’t tell me to stop smoking” printed on it. No one could make her over.