N

ov. 27, 2007, was a hot and humid Tuesday in Manila, Philippines, and David Bunevacz was getting the shit kicked out of him.

He had been invited to the home of one of his partners in a recent cosmetic surgery venture, the Beverly Hills 6750 clinic in Makati City, he later told authorities, according to records of legal proceedings in the Philippines. Just after noon, he pulled up in his black Porsche Cayenne Turbo. Before he could even step out of his car, however, he was unceremoniously dragged from the driver’s seat and ordered inside. In the living room, he found himself outnumbered, surrounded by five of his business partners and three men he’d never seen before. They were all angry.

His partners began interrogating him about company spending. Unbeknownst to him, they had audited the clinic’s finances and saw more than $2,000 had been spent on a luxury vacation in Bunevacz’ name. Roughly $15,000 more from company coffers had bankrolled car insurance and a payment for a BMW X5 SUV, much like the one Bunevacz had recently presented to his wife, the model and talent agent Jessica Rodriguez, after she appeared on the Filipino TV singing competition Celebrity Duets.

To hear Bunevacz tell it in a later deposition, however, the other men were driven by greed. They wanted his shares of the company for themselves, plain and simple.

Irate, they demanded Bunevacz resign. To punctuate the point, he claimed, one of the partners took off his watch, wrapped it around his fist, and pounded Bunevacz in the face and neck, while another yelled insults at him. The first man stopped hitting him, only to pull out a gun.

Or was it six guns?

When Bunevacz initially told this story to investigators, there was one firearm. When he was deposed, years later, in a separate matter, there were half a dozen. Either way, he’d later say the partners demanded he sign over his shares of the company. They took his cell phone, his Hublot watch, and the keys to the Porsche. It was only during a lucky moment when his captors were preoccupied that, Bunevacz would later say, he made a break for the door. He ran into the thick afternoon air and down the street, hailing a cab.

“I got in a taxi all bloodied up, went home, called my wife en route, and told her to get out of the building,” he said in the deposition, contradicting his earlier claim that his phone was taken.

The business partners — one of whom recently got 18 years in prison for embezzlement and another of whom was facing attempted murder charges as of 2018 — told authorities they merely “confronted” Bunevacz about his alleged misuse of company money, and he “failed to offer a satisfactory explanation.” Bunevacz fled the country within weeks, in December 2007, taking his wife, young daughter, and two stepchildren with him. He sued his ex-partners and was later charged with fraud in the Philippines, although he has since claimed the warrant for his arrest has been lifted. In a 2010 deposition, an attorney asked him why he’d returned to the U.S. “I was kidnapped by my former partners and it was time to leave,” he’d answered. “Good enough reason?”

David and Jessica Bunevacz

Courtesy of the Danford family

BUNEVACZ, WHO THROUGH lawyers declined to be interviewed by Rolling Stone, will always be the hero of his own story. His dubious recounting of the run-in with his former cosmetic surgery partners demonstrates how he experiences his entire life. The beat-down in the Philippines was far from the only time he was accused of misappropriating other people’s money. In fact, according to a sprawling federal fraud case against him, it was just the beginning.

In 2022, a judge found that between 2010 and 2020, he’d scammed money from people in nearly every area of his life — from business partners to his close friends in Los Angeles to parents of the girls who rode horses with his youngest daughter. In the end, the court found, he took at least $35 million from more than 100 people. Law enforcement officers who investigated Bunevacz said they’d found evidence that he’d barely conducted any legitimate business at all during that time frame.

Bunevacz isn’t the world’s biggest grifter. People steal millions — or more — from each other, from companies, and from the government, all the time. What makes Bunevacz stand out is his brazenness. Attorney Jim Moriarty, who represented one victim in a legal fight against Bunevacz, calls him “the single most amoral person” he’s ever encountered. Bunevacz’ dentist — whom he took for $800,000 — said in court that Bunevacz’ “cold-heartedness” was “sociopathic.” He called him a next-level crook with “no capacity to understand the hurt that he’s put on all his victims.”

Bunevacz flaunted his riches. He drove luxury cars and showered his wife with gold and diamond jewelry. He threw extravagant parties for his family, bought horses for his youngest daughter, and moved them all into a Calabasas mansion formerly owned by Kylie Jenner. They traveled constantly, sometimes by private jet, documenting their exploits on social media. His youngest daughter, Breanna, and his wife even appeared on two reality TV shows together. As a unit, the Bunevaczes kept anything but a low profile.

Jessica and Breanna declined through a representative to be interviewed. None of Bunevacz’ family members was criminally charged in his scams. His eldest daughter, Mary, 34, who goes by her middle name, “Hayca,” was sued in 2022 in a civil matter, alongside her father, by the Securities and Exchange Commission for unlawful sales of securities related to the scams detailed in the federal criminal case. The SEC accused Hayca of joining her father in meetings with potential investors, during which she discussed her own apparent background working in the vape industry. In a March judgment, Hayca was ordered to pay the SEC more than $60,000 but did not have to admit to or deny the allegations in the complaint. She declined, through her lawyer, to be interviewed and declined to comment on the SEC’s allegations. The SEC found Bunevacz liable for $35 million.

His shameless display of wealth caught the attention of people who saw what he had and wanted it. “I’m gonna use a dirty word, but people are greedy,” says David Lingscheit, a retired detective for the L.A. Sheriff’s Department’s fraud and cybercrimes bureau who worked on a 2016 felony case against Bunevacz. “They want something for nothing.”

It didn’t hurt that he looked the part. Classically tall, dark, and handsome, with a square jaw and an athlete’s build, he claimed on his website to stand six feet, four inches tall, looking every inch the former model that he was as a young man in the Philippines.

Ellen Cousins, a certified fraud examiner who investigated Bunevacz as part of a lawsuit in the 2010s, keeps a photo of Bunevacz looking “steamy and evil,” as she puts it, on a bulletin board in her office. It’s a portrait from his modeling days. He’s fixing the camera with an intent, smoldering gaze out from under his lowered brow and tousled, damp-looking locks. “He offends me,” Cousins says.

“I truly believe he thinks it’s his money,” says Bill Sewell, a friend who got taken for $50,000. “He’s shaping his world. And if anyone tries to take him out of that world, they’re a threat, because you’re attacking what really is the most important thing to him, which is his fantasy.”

In the picture Cousins keeps by her desk, he appears to be doing an impression of a bad-boy come hither look. But there’s no hint of a smile on his lips, no twinkle of an invitation in his eyes — only blank intensity. He looks ready to be whoever he needs to be. He looks ready to win.

Bunevacz home in Calabasas, once owned by Kylie Jenner

U.S. District Court

DAVID BUNEVACZ WAS BORN on Dec. 20, 1968, in Torrance, California, the only son of immigrants. His mother, Filomena, came from the Philippines to work as a registered nurse in Canada before moving to California. His Hungarian father, Joseph, was a high-ranking athlete himself, on his landlocked country’s national dinghy-sailing team, and a storyteller. In 2020, he appeared in a New Yorker article on antibiotic-resistant illnesses (he suffers from a rare, recurrent blood infection), but the interviewer struggled to keep him on topic. Rather than discussing his medical condition, Joseph — who reportedly dressed in a Hungarian Olympic tracksuit for the occasion — “just wanted to tell wild, improbable stories about his younger years,” according to the article. He said that in 1960, after competing in a regatta in Bavaria, Germany, he fled to Munich to escape communist rule. There, he claimed, he’d met the Beatles in a club and taught them how to ski. Eventually, he landed in Los Angeles, where he met Filomena. Joseph and Filomena did not respond to an interview request.

During Bunevacz’ adolescence, his parents struggled financially. Joseph ran an event and travel agency, and, ahead of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, he arranged to broker $2.5 million worth of travel on behalf of Hungarian clients. When Hungary joined the Soviet Union in boycotting the games, however, he lost several nonrefundable deposits. That fall, he and Filomena filed for voluntary Chapter 13 Bankruptcy. Their finances never quite recovered; in 1992, they filed for bankruptcy again.

Bunevacz seemed determined from an early age to make something of himself. He inherited his father’s propensity for athletics. In 1988, he attended UCLA on a track and field scholarship, where he specialized in the javelin. (He still ranks fourth among the longest throws in the university’s history.) While in college, Bunevacz committed his first documented crimes. Between 1991 and 1994, he was found guilty by pleas of no contest to misdemeanor counts of theft, burglary, forgery, and fraud. Before he graduated in 1993, Bunevacz’ scamming career had already begun.

At the same time, Bunevacz, who by then was also competing in the decathlon, was busy building his resume as an athlete. Around 1995, he was recruited to the Philippines national track team. Officials there hoped he would earn the nation its first Olympic gold medal, and seemingly pulled strings to get a U.S.-born athlete on the team. He never competed in the Olympics, however, and became better known for spending his hefty stipend partying and dating actresses and models, landing him in the pages of Filipino tabloids. He landed some TV work and acted in a few Filipino films, including the action comedy Tusong Twosome (2001) and the boxing movie Buhay Kamao (2001).

In 1999, authorities stopped his then-girlfriend, Filipina-American actress Anjanette Abayari, at an airport in Guam for drug possession (she denied it was hers, but paid a fine and went back to the U.S.). While she was detained, Bunevacz reportedly sold off her belongings, according to Abayari, including a car and a Rolex watch. “My uncle recovered the car; the Rolex, not,” she told a Filipino outlet in 2015.

Less than a year later, Bunevacz married Jessica Rodriguez, a model and supposedly a close friend of Abayari’s. She worked in the entertainment industry, reportedly co-presenting a subtitled version of Extreme Makeover for Filipino audiences. Bunevacz adopted her son and daughter, and the couple had another daughter, Breanna, in 2003.

Bunevacz has said it was Jessica’s idea to open the clinic to do “cosmetic surgery…dermatology, dentistry, all of the cosmetic innovations that a woman would need,” he said in a 2010 deposition. After it opened in 2005, Jessica launched a reality-style campaign called Miss Ugly No More to give one lucky woman a makeover — before the business partners, he claimed, ran them out of the country. Citing a media report from the Philippines, a filing in the 2022 federal case described the business as “an elite cosmetic surgery clinic catering to Manila’s high society.” The same report added, “Insiders at the clinic say the couple has an insatiable appetite for the good life.”

2010 David Bunevacz deposition

WHEN BUNEVACZ RETURNED to the U.S., he began building himself a lifestyle worthy of the American dream. His first major U.S. scam was one of his largest ever — an outrageous Olympics tickets hustle, where he sold a broker 17,000 tickets for the 2010 Vancouver games — tickets that never materialized. That victim, Gene Hammett, eventually got a civil judgment against him, but never recovered the $3 million he’d paid. He lost his house, his savings, his business, and nearly his marriage. “I thought we’d be back on our feet sooner, but for years it was a real struggle,” Hammett says.

Cousins, the fraud examiner, learned about Bunevacz while doing research for Hammett’s case. “It was so clear that he was a serial criminal and that no one was stopping him,” she says. “He would slip away, paying a minimal penalty — or no penalty — and then just do it again. He didn’t seem to be afraid of anyone.”

Bunevacz dabbled in several other businesses around the same time, from an overseas iron-sands mining operation to a company that sold vitamins. Lawsuits from investors dogged him along the way. Soon, he zeroed in on the burgeoning electronic cigarette industry.

In 2012, he lent startup money to vape manufacturing company Grenco Science, creators of the G Pen, a well-known product once marketed by Snoop Dogg. Long after Grenco repaid the loan, however, Bunevacz continued to falsely claim affiliation with the company to draw investors to his own false ventures. “I always kind of had a strange feeling about him,” says Chris Folkerts, Grenco’s actual co-founder. “It was very clearly stated that I had no intention of wanting him to be part of the company.” Soon, Grenco got pulled into a lawsuit by another one of Bunevacz’ victims and had to prove to a judge they were not affiliated with him, despite his claims. The court eventually dismissed Grenco from the case and ruled against Bunevacz.

If Bunevacz was intimidated by the constant lawsuits, he didn’t show it. He seemed to always find more money to move around. Meanwhile, he was building the lifestyle he’d wanted — a glittering, glamorous one that attracted new victims like a chrome fishing lure flashing underwater.

•••

In 2014, Bunevacz met the Danfords. Tom Danford, a broad-shouldered former college tennis player who’d acted in commercials and short films, had moved his family from Minnesota to Southern California in 2011 to work in internet advertising. His wife, Meredith, taught spin classes at the Paseo Club, an upscale athletic club in Valencia that Bunevacz and Jessica also belonged to.

Relative newcomers to Southern California, the Danfords were astonished by the Bunevaczes’ wealth. They drove Audis and BMWs, lived in a sparkling McMansion overlooking a manmade lake, and were always surrounded by a glitzy group of beautiful L.A. people. The roster was seemingly hand-chosen by the Bunevaczes and included, at times, Backstreet Boy Kevin Richardson and actor Ryan McPartlin, from NBC’s Chuck. (Neither responded to requests for comment.) Soon, the Danfords were a part of the group, too. “Jessica would say, ‘We are the group of Valencia, and everyone wants to be who we are,’” Meredith recalls.

A few months after they’d met, the Danfords and Bunevaczes attended a New Year’s Eve party together. There, the Bunevaczes talked about a trip they were planning to the Bahamas. They said the Danfords had to join them. It felt fast. “They were like, you guys are coming; it’s not for another year, so we’ll put it all together,” Tom says. “I’m like, I don’t know you guys. But at the same time, I don’t want to not get invited, you know? I want to be invited.” They were in.

That October, Meredith and Tom stood in the sand on a private beach with roughly 30 other people. The guests were dressed all in white — per Jessica’s instructions. A yacht and a speedboat had ferried the partygoers over from the Paradise Island resort where Bunevacz was paying the bill. As the afternoon light stretched over the sand, Bunevacz, in a white linen button-down, and Jessica, in a custom, seashell pink mini dress, stood barefoot in front of family and friends and renewed their vows for their 15th wedding anniversary.

Later, back at the resort, Meredith cradled a blue Tiffany & Co. box on her lap. Bunevacz had given all the women gold hoop earrings from the designer to celebrate his and Jessica’s “wedding day,” as he called it. As guests lingered over a candlelit meal and wine, Bunevacz stood to address the people seated around him at a long banquet table. He spoke, in several unfinished clauses, about his own largesse. “There is a serious reason why all of you are here today,” he said, in a video clip obtained by Rolling Stone, then touched his hand to his heart. “Because we wanted you here today, because – what my parents have instilled in me: the generosity, in which they give every single person they truly feel is a part of their family — and I have gained that.”

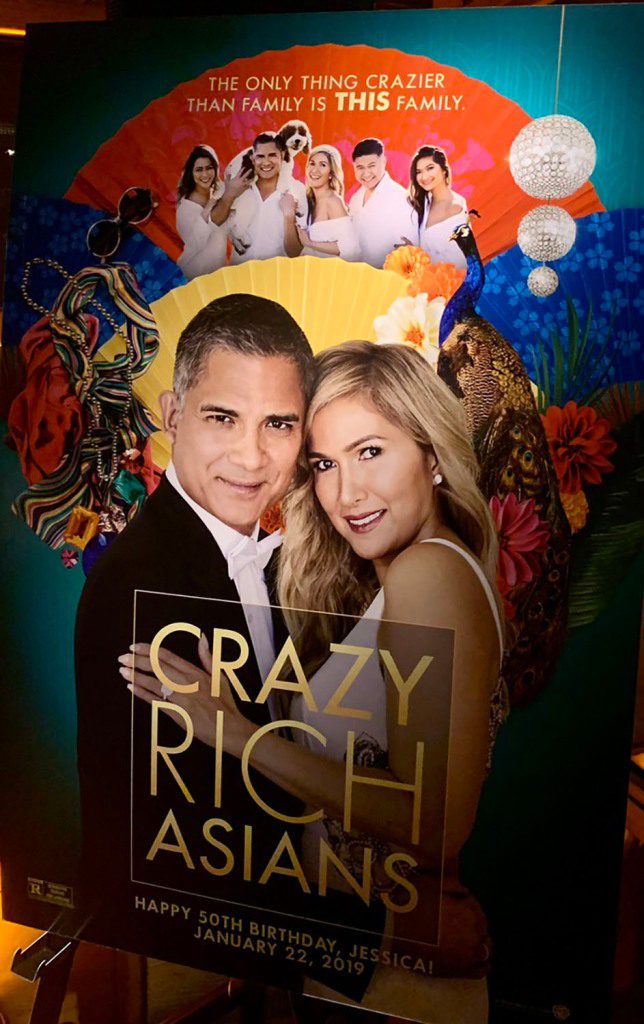

David and Jessica Bunevacz display image at Jessica’s 50th birthday party

For the Danfords, the Bahamas trip was only the beginning. In the coming years, they went with them to Chicago, New York, and Las Vegas, celebrated birthdays and holidays together in Palm Springs, and took ski trips to Mammoth Mountain with their kids. Sometimes their new friends’ incredible generosity felt weird, like when Bunevacz crashed a girls’ trip to Vegas and gave the women $5,000 in cash, challenging them to spend it all by the end of the day. “He liked being the guy,” Meredith says.

The Danfords didn’t often talk about work with the Bunevaczes, but they knew he worked in the electronic cigarette business. By 2014, e-cigarettes had become young consumers’ definitive tobacco product of choice, so when Bunevacz asked him for a couple small bridge loans for his business, it didn’t strike Tom as unusual. He lent Bunevacz a few thousand, and it was paid back, as promised. Then, in 2016, after nearly two years of playing tennis together at the athletic club and several more luxurious vacations, Bunevacz offered Tom the chance to be a partial owner in an e-cigarette company. Tom wanted in. He had his lawyer look over some paperwork from Bunevacz, cashed out his savings, and handed Bunevacz $200,000.

That November, cannabis was legalized in California. Cousins, the certified fraud examiner, knew Bunevacz wouldn’t miss that opportunity. “The minute that the cannabis stuff was legalized in California, I was like, he’s gonna be there,” she says. “It’s a huge cash business, he’s been dealing with vaping fraud for awhile, and of course that’s what he did.”

One day late in the year, Bunevacz drove Tom in his brand new Porsche to see the future site of their business. He told Tom that they were out of the e-cigarette game. Instead, he’d taken Tom’s money and put it toward a company with a cannabis grow right there in Los Angeles. The company was poised to go public, he promised, and Tom was going to own a big portion of it. They pulled up to a 64,000-square-foot warehouse, the insides of which were still being built out. There were workers there wearing hardhats who seemed to know Bunevacz. They’d just begun outfitting the space for cannabis cultivation, with lighting and several separate rooms for the crop. Progress was slow.

“What advancements have been made?” Tom remembers asking his friend during later visits to the space. “When is this thing getting up?” Now, he looks back and says: “I never saw a plant in there, ever.”

One night, feeling restless about his investment, Tom Googled Bunevacz and found a Wikipedia page cataloging his athletic accomplishments. There was also a section on criminal history. The next time they were driving back from the grow site, he asked him about it.

“Dude, it says that you got arrested and you spent the night in jail,” Danford said.

“What are you talking about?” he remembers Bunevacz responding. “I never got arrested.”

Bunevacz shrugged it off. The next day, Danford says, that part of the entry had disappeared.

BUNEVACZ WAS FACING ONE lawsuit after another, but he kept his troubles under wraps. Tom did not even know it when, in August 2016, the L.A. County District Attorney’s Office charged Bunevacz with nine felonies for grand theft, unlawful sale of securities, and prohibited securities practices. Lingscheit, the since-retired L.A. Sheriff’s Department detective who worked on the case, says Bunevacz was taking money — as much as $400,000 in the case of one victim — from people who thought they were investing in businesses he owned, including entities called Holy Smokes and Grenco. Then, he’d route the money through shell companies before spending it at casinos and on personal expenses.

“He’s doing everything that he could do to appear as if he was successful,” Lingscheit says of Bunevacz’ strategy for luring more victims. “It is basically window dressing.” Bunevacz took a plea deal and was sentenced in 2017 to 360 days in jail and three years of probation. After he paid restitution to the victims, however, the court stayed his jail sentence.

Meanwhile, Jessica and Breanna were attempting to launch reality TV show careers. Jessica hosted a lifestyle podcast for three years called The Polished Woman and, in 2016, self-published a book of dating advice. She also managed Breanna’s burgeoning modeling career. In 2018, mother and daughter appeared together on a Lifetime reality show called Making a Model With Yolanda Hadid. On the show, Breanna competed with other children for a modeling contract, doing photoshoot challenges and mock interviews with agencies. At one point, Breanna, just 13 during production, gave Jessica a pep talk after a tough challenge. “The game’s not over till it’s over,” she said. “That’s what Dad taught me.”

Bunevacz and his youngest daughter were close. “He held her up like she was the most important thing,” Danford says, adding that he doesn’t blame her for her father’s behavior. “Everything she did — she walked on water.”

Her Sweet Sixteen party was a red-carpet affair, decorated with white balloons and oversized neon mushroom sculptures lit by black lights. Guests dressed all in white, and Bunevacz hired acts including rappers A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie and Ski Mask The Slump God to perform, while hype men in LED robot suits shot lasers into the crowd. According to federal authorities, the event cost more than $200,000.

None of those expenditures came close, however, to the more than $8 million Bunevacz spent gambling. According to people who thought they knew him, when Bunevacz was on the casino floor, he was in his element. He seemed comfortable, like he felt at home — and in control. His go-to game was Blackjack. “He would have the pit bosses give him the green light so that he could take the entire table,” says Danford, who, with Meredith, took several trips with Bunevacz and Jessica to Las Vegas. “He’d have $10,000 hands on the whole thing.” The couple once saw him make a show of giving a $10,000 poker chip to a cleaning lady who was Filipina. “He let everyone see it,” Meredith says.

There was a darker side to his gambling, too. “On one point, he loved the crowd, but then on the other point, he would say that he would go in at 6:00 in the morning when the vacuums were going off,” Danford says. “I was never there at the table at 6:00 in the morning, so I don’t know.” Bunevacz once told him he had an addiction, though. “It might have been a throwaway comment, but he said, ‘Yeah, I got a gambling problem,’” Danford says.

Bunevacz’ big spending at the tables regularly caused tension with his wife. Meredith says when he was playing cards, Jessica would come by and take his winnings off the table. “She put the cash in her purse cause she didn’t want him gambling it all,” she recalls. “She would get upset every time they went to Vegas. She never wanted him to go alone.”

Breanna and Jessica Bunevacz on E!’s Raising a F***ing Star

Last September, on another reality show, E’s Raising a F***ing Star, the family alluded to struggling financially. During the season, Jessica was on a mission to boost Breanna’s career because the family had run into money struggles during the pandemic. “That’s why I told Breanna, ‘it’s about time that you work,’” she said. Breanna, then in high school, said she felt pressured to contribute to her family’s income. “It would be nice just being a kid and not having to worry about working,” she said. Bunevacz himself appeared briefly in the first episode, wearing a beige polo shirt and seated at an outdoor cafe table with his family. He chided his eldest daughter for not having her hair done, then talked casually about his struggle to find a less expensive house for them. A disclaimer flashed on the screen: “Dave Bunevacz was charged with fraud after the show completed production. This event and its aftermath are not part of this series.”

The reality shows played up Jessica’s modeling background, showing her encouraging her daughter to follow in her footsteps. But growing up, Breanna’s heart was in horseback riding. She was good at it, too. By age 14, she was winning blue ribbons in national equitation competitions. “If you think about a ballet dancer, you want long legs and that whole look, and she had it,” says the mother of another rider who used to compete with Breanna. “She was a good athlete and she cared about it.”

Bill Sewell, whose daughter rode at the same barn as Breanna, remembers the first time he saw Bunevacz and Jessica, pulling in to park at the barn. “They show up, and he’s in a Lamborghini Urus SUV — yellow,” he tells Rolling Stone. “She’s in the pink Bentley. They definitely stood out. Beautiful couple.”

Breanna and Sewell’s daughter together rode at a barn in the pastoral oasis of Hidden Hills, a gated town in the Santa Monica mountains. Bunevacz seemed to fit right into the moneyed horse world. Sewell says he was “very articulate” and spoke with authority: “The kind of guy who would never raise any suspicion or any flags.” When Bunevacz asked Sewell for a six-month loan, Sewell, a longtime entrepreneur, gave him $50,000. But he was looking for more.

Bunevacz asked the mother of the other rider if she wanted in on his latest cannabis business, but she didn’t. Then he asked her for a loan for a totally different reason: He told her a horse had come up for sale on the East Coast and that Breanna loved it. He was short on cash, though, because he was waiting for a big payment to come in.

“He said, if I don’t get this horse now, it’s going to be gone,” says the mom, who asked to remain anonymous. “If it’s a really good horse with a tried and true record, it’s gonna go fast.” She had the money, and she wanted Breanna — whom she calls a “kickass rider” — to have the horse. In November of 2019, she lent Bunevacz $250,000 to buy a $500,000 horse.

Bunevacz had found the key to getting real money from the horse crowd. He borrowed $250,000 from at least one other parent of a rider, as well as the head trainer at Breanna’s barn, according to the trainer, who asked not to be named. “He wreaked havoc on the entire horse community,” the trainer says. He’d funded a horse and a half entirely with other people’s money, the trainer says — money he subsequently failed to repay. Once she realized Bunevacz wasn’t going to pay her back, the trainer was able to resell the animal and get back her money — but not before having to pay the transporters, veterinarians, and other vendors who Bunevacz had stiffed during the transaction. The trainer calls Bunevacz “the Tinder Swindler of the horse industry.”

BUNEVACZ’S SCHEMING WAS about to catch up with him. In March of 2019, Danford told him he was done. “I want out, bro,” Danford told Bunevacz in texts reviewed by Rolling Stone. “I’ve asked for weeks for documentation and haven’t heard a word. And when I ask for my money back then I get pushback. I’m not comfortable with any of it.” That’s when Bunevacz’ tone flipped. “Then lawyer up!!” he shot back. Looking back, Danford laughs. “That’s when he showed his little fangs,” he says.

That fall, a publicly traded Canadian company and its president sued Bunevacz for breach of contract over loans they’d given him totalling $4.6 million. The investors thought it was going toward the production of vape pens, which never arrived. That dollar amount seemed to be enough to catch the attention of the authorities.

In 2020, Detective Geoffrey Elliott, who’d succeeded Lingscheit in the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department’s fraud and cyber crimes bureau, took the case. He says it’s not uncommon for fraud cases to take a while to gather momentum in the legal system. “A lot of times, victims will come, and if it’s a one-off, not a large sum of money, sometimes it looks like a civil matter, not necessarily a criminal investigation,” Elliott says, referring broadly to investment fraud cases. This can be frustrating for victims of financial crimes, he acknowledges, but says that if those one-off violations went before a judge, they likely wouldn’t result in a significant sentence. Waiting to build a bigger case can pay off for victims, the way it did with Bunevacz. “If you take the totality of what he did, that’s why it was able to go the distance it went,” Elliott says.

Breanna Bunevacz on Vondel

Jump Media

Starting in late 2020, Elliott subpoenaed Bunevacz’ bank records and collected statements from dozens of victims. In mid-2021, he looped in the federal authorities, based on the number of victims and the amount of money he’d taken.

Around 9 a.m. on the morning of April 5, 2022, Elliott and a team of law enforcement officers knocked on the door of the mansion on Prado de Oro in Calabasas, California, where the Bunevaczes were living at the time. It had dark wood floors and cold white walls. From inside the entryway, you could look through the living room, past the imposing, metal chandelier and stone fireplace and out the french doors to the pool deck. The sprawling property was quiet that morning as the officers took Bunevacz away in handcuffs. “I believe his daughter was upstairs in bed,” Elliott says. “But I didn’t need really to go in. We got what we came for and left.”

Bunevacz was booked on wire fraud charges. In an affidavit, authorities called him a “peripatetic grifter” who “frequently bragged about his wealth.” Authorities estimated that between 2010 and 2022, he’d taken between $37 million and $45 million from would-be investors and only repaid a fraction of it. The charges carried a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison.

The millions of dollars Bunevacz had taken from victims hardly went to a single legitimate business venture, as far as authorities found. Instead, Bunevacz had spent the funds on his ostentatiously lavish lifestyle. According to prosecutors, this included his gambling, $18,000 monthly rent on the Jenner mansion (which they did not own, something Jessica didn’t mention on E!’s Raising a F**king Star), Audi car payments, the purchase of a Belgian sport horse named Vondel, an 18-karat white gold diamond ring, two Birkin bags, a Rolex — purchased days after he was sentenced for his state-level crimes — and Breanna’s Sweet Sixteen birthday party.

After the arrest, the family kept up appearances on social media. Jessica promoted the September premiere of the reality show and posted images of herself by the seashore and on a girls’ day out at a Veuve Clicquot event. Breanna continued modeling and has an EDM single out.

David and Jessica Bunevacz

IN JULY 2022, BUNEVACZ pleaded guilty to federal wire fraud and securities fraud charges, and seven months after he was arrested, on a bright November day in Los Angeles, he arrived in court to be sentenced. Wearing a cream-colored jumpsuit and ankle shackles, his graying hair buzzed close to his head, he stared straight ahead or down at his lap as half a dozen victims, including Danford and Sewell, gave impact statements. Each recounted the betrayal of trust and the financial loss they’d experienced. Speakers called Bunevacz “ruthless,” “conniving,” “manipulative,” “malevolent,” and “evil.”

Danford asked the judge to mete out the maximum sentence. “If he’s let out…he’ll do it again,” he said. “He knows no other way.” Sewell said that it was hard to see Bunevacz’ family “living their best lives” online while his money was still missing. “We’re watching them continue to be princesses in the social media realm and it’s…just unbelievably frustrating,” he told the judge.

Bunevacz wrote a brief letter to the judge, just 250 words long, asking for leniency. He seemed at a loss to explain himself. “I am extremely sorry and will never forget the trail of damage I have left behind,” it read. “There is obviously no excuse for what I did.” His family wrote to the judge, too. Jessica blamed his gambling addiction. “We do not need any material things,” she wrote. “He knew of this from the beginning he married me” [sic].

As Judge Dale S. Fischer of the Central District of California spoke, Bunevacz shrank in his chair. “I am not in the least persuaded that Mr. Bunevacz regrets anything other than that he was caught,” she said, before sentencing him to 17 and a half years in prison, far beyond the prosecution’s request for 11 years. She also ordered him to pay $35 million in restitution. With that, Bunevacz was taken away to prison. His family did not make statements at the hearing and did not appear to be present in the courtroom for his sentencing.

Bunevacz is currently serving time at Terminal Island, a low-security men’s prison on the Port of Los Angeles. He has appealed his sentence, with an opening brief due Aug. 4. Bunevacz’ federal public defender in his criminal case did not respond to multiple requests for an interview with Bunevacz. One of his appeals attorneys, also a federal public defender, declined to make Bunevacz available for an interview and declined to comment on the allegations against him.

Meanwhile, his wife and children carry on without him. In April, Jessica posted photos from a trip to the Philippines where she said she met with the secretary of tourism. Breanna turned 20 and recently posted a video of herself riding horses again. In an interview for a November 2022 digital cover of independent fashion magazine Reserved, she sounded like she’d found a new hero. “My mom is the biggest influence in my life,” she said. “She has been through so much and yet she loves her family unconditionally….I wouldn’t be who I am today without her.”

In their impact statements in court, multiple victims begged the judge to protect them — financially — from Buenvacz. They’re worried the prison sentence he got isn’t enough. “I think he’ll be out by the time he’s 70, and he’ll still be figuring out how to steal from people,” Danford says. “That’s all he knows.” Bunevacz was good at grifting. All he needed was a fresh lease on a luxury car, a rental mansion and a nice suit. The supply of people ready to be taken in seemed endless. Meredith Danford says, “We drank the Kool-aid.” Gene Hammett, the Olympic tickets victim from way back in 2010 put it more bluntly: “He had a story that I bought.”