T

he evening of the fight, Nathan Valencia was nervous. It was the first time that Valencia, a member of Sigma Alpha Epsilon at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas had participated in Fight Night, the annual event hosted by rival fraternity Kappa Sigma. Like other frat functions, Fight Night was for charity. But this particular event had a dangerous reputation, known for landing participants in the ER with broken noses and concussions.

This hadn’t deterred Valencia, a charming and popular junior, from signing up. He’d been assigned to the card’s main event, fighting Emmanuel Aleman, a fellow student and member of Kappa Sigma.

When Valencia and his girlfriend, Lacey Foster, pulled up to the Sahara Events Center — a dank-smelling roller-hockey rink just a mile off the Strip, wedged between a swingers club, a bathhouse, and several abandoned storefronts — something immediately felt off. Valencia and Foster entered to find the boxing ring stuck into one corner, surrounded by a hundred or so folding chairs. The scene had the look and feel of a legitimate boxing event — gloves, mouth guards, ring girls in short-shorts holding up cards to announce the rounds. But it was haphazard, too: a pile of trash in a corner of the venue, the dingy warm-up room cluttered with old hockey gear. “We were like, ‘What the heck is going on?’” Foster says.

There were nine fights that night. In each one, the opponents boxed three rounds of three minutes each, or until they appeared unable to fight back. They wore headgear, mouth guards, and gloves. Most fighters had a fraternity brother or close friend in their corner to provide pep talks and coaching.

Despite this adherence to basic boxing protocol, people in attendance would later describe the event as “chaotic” and “disorganized.” In one of the early matches that night, a fighter’s headgear came loose. When someone in the crowd screamed to stop the fight, the referee — who’d been seen drinking a beer — seemingly ignored it. There was an uneasy tension in the air. By the time Valencia was up, it was nearly 10 p.m., and the crowd, which had been drinking at the venue’s bar, had teetered from tipsy to drunk.

“Nathan Valenciaaaa,” the emcee roared into the mic as the audience cheered. Valencia, stone sober, appeared serious and apprehensive as he made his way across the room. Shirtless, in red headgear and black shorts, he shrugged off an oversize purple fraternity jacket and climbed into the ring.

For a few uncomfortably long moments, Valencia paced alone in the ring as 2Pac’s “Ambitionz Az a Fighta” boomed over the sound system. Then, the emcee called the name of his opponent. As Emmanuel Aleman entered — lean and muscular, in white shorts, with a purposeful, confident stride — he tapped Valencia’s glove with his own. The two shadowboxed in their corners before the fight began.

In a video of the match, it’s clear they’re both amateurs. As the fight began, they lunged at each other fist-first, swatting and punching, slapping gloves down on each other’s heads, and rarely connecting a straight shot. They hit each other in the face and body, but also areas like the leg, which is out of bounds in boxing matches at any level.

The ref largely held back, though he halted the fight momentarily to tell Valencia to stop hitting the back of Aleman’s neck. Both fighters appeared coherent, if out of their element. By the end of the first round, Valencia had grown slightly winded, but was still fighting — clubbing the top of Aleman’s head, knocking his ill-fitting headgear to one side.

As the rounds continued, the fight grew more erratic. The two threw random blows, their movements sloppy and imprecise, the frenzied strokes of a parking-lot brawl. And then Aleman had Valencia cornered, landing punch after punch into his head until Valencia broke free and sprinted across the ring. As Valencia ran, dodging Aleman’s blows, he looked exhausted. By the time the referee called the fight at the end of the final round, Valencia could barely stand. Aleman gave Valencia a quick hug, then Valencia leaned over the ropes, struggling to hold himself up.

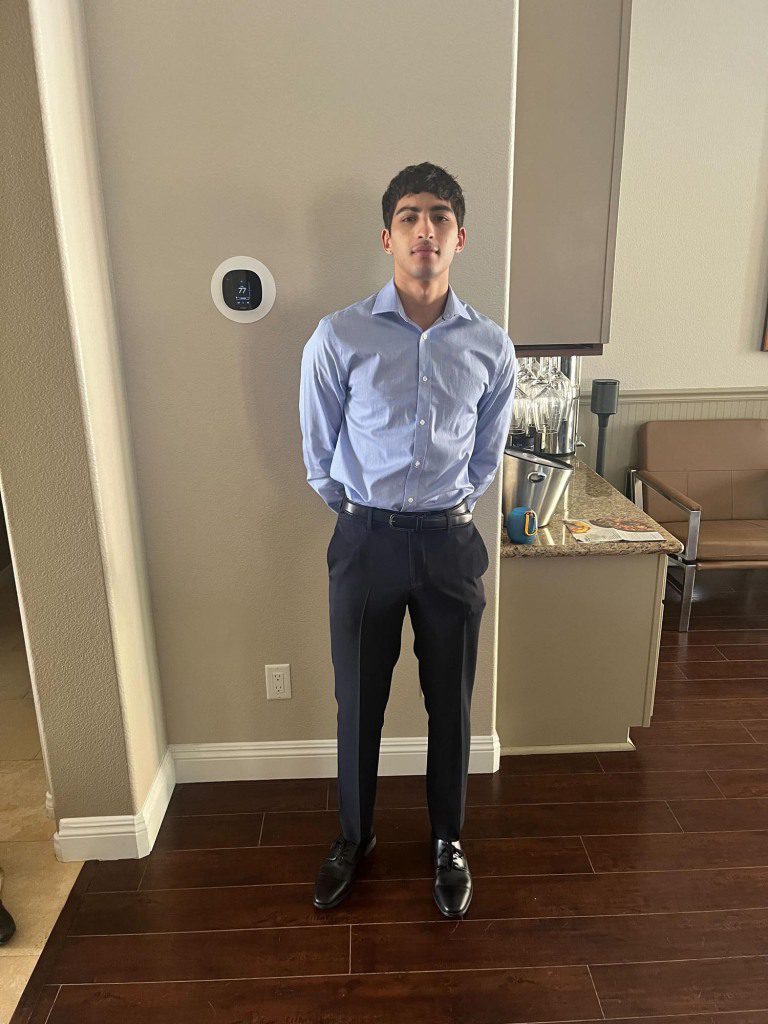

Nathan Valencia with his girlfriend, Lacey Foster.

COURTESY OF THE VALENCIA FAMILY

Foster stepped up to see how he was doing. “I’ve never seen someone so tired,” she says. She climbed in beside him, patting his back, telling him he did a good job. But by then, “he was staring past me,” she says. “It looked like his consciousness was disappearing.”

Aleman never saw it coming. “He was fine the whole fight,” he says. “At the end, he sat down. When he couldn’t get up, I thought he was tired.”

The crowd was growing rowdy. In the audience, a brawl broke out and spectators shouted and pushed against each other. In the ring, Valencia suddenly collapsed. People climbed into the ring beside Foster as Valencia lay beside her, barely breathing. A panic-stricken woman, who authorities would later say claimed to be a nurse, attempted to give Valencia water. Then, according to one witness, she dragged his inert body across the ring by his ankles, in an attempt to move him away from the crush of bystanders clamoring into the ring.

An attendee called 911. “We have nurses here but we need, like, real medical assistance,” she begged. When EMTs arrived eight minutes later, they classified Valencia a “Gus Trauma” — the medical equivalent to “John Doe” — because the people attending to him, including the frat’s medical personnel, were so intoxicated they couldn’t “coherently articulate his name,” according to interviews cited in the subsequent attorney general’s report. Valencia was rushed to the hospital, where he spent three days in a coma. On Nov. 23, 2021, at 2:46 p.m., he was pronounced dead.

Later, in the days that followed, a news story detailing the evening’s proceedings would describe Fight Night as a “diabolical underground fight club.” In reality, there was nothing underground about Fight Night, which existed with both full knowledge of its sponsoring fraternity and UNLV. Similar events take place at dozens of colleges and universities across the United States each year, pitting members of fraternities and sororities against one another in what is supposed to be a show of charity and collegiate camaraderie. This event was anything but. According to the attorney general’s report, dozens of interviews, and a lawsuit filed by Valencia’s parents, Kappa Sigma’s Las Vegas Fight Night was an unregulated and dangerous event. It was only a matter of time before someone was going to die.

FRATERNITY BOXING MATCHES date back more than a century. Though Kappa Sigma’s Fight Night was introduced in Alabama in 1994, as a way for fraternities to contribute to philanthropic causes, it was first held at UNLV in 2011, and has emerged as one of the biggest Greek events affiliated with the university. In its second year, boxer Floyd Mayweather donated nearly $50,000 to a Fight Night charity cause after hearing about it. While only about 100 people showed up to watch the 2021 matches, countless others watched online. “If you’re not participating, then you’re watching, and if you’re not watching there, then you’re watching on someone’s Instagram Live,” says Makamae Aquino, a former member of the Zeta Tau Alpha sorority who fought in 2019.

According to multiple UNLV students, the event has a reputation of being dangerous — which, for many participants, is a part of its appeal. “If someone signs up with an expectation that nothing will happen, and that no blood will be shed, they are obviously mistaken,” says Manny Tapia, who fought in three Fight Nights. “It’s bound to happen.”

Many of the students who participate have never boxed before — the flyers posted around campus stated “no experience required” — meaning they don’t understand “the full context of what [they’re] signing up for,” says Christian Paskevicius, a former member of Sigma Alpha Mu who fought in two Fight Nights. “[Kappa Sigma] expects that people who don’t know what they’re doing could potentially hurt people less.” Instead, this lack of experience often leads to serious injuries meted out by amateur fighters. (Kappa Sigma declined multiple interview requests and declined to comment on a detailed list of allegations.)

Emmanuel Aleman

COURTESY OF EMMANUEL ALEMAN

Boxing, of course, is dangerous by design — which is why it’s one of the most heavily regulated sports in the country. There’s a stark difference between pro boxing, where the goal is to make money and ideally knock out your opponent, and amateur boxing like UNLV’s Fight Night, where the goal is to score points by landing and avoiding certain hits. According to the amateur rules, a fight should be stopped the moment a fighter exhibits bleeding, cuts, or swelling.

At least, that’s how these fights are supposed to go. When the sport is properly supervised, it can be “one of the safest sports out there,” says Mike McAtee, the executive director of USA Boxing, the national governing body of amateur boxing. But injuries — both superficial and otherwise — are a possibility for any fighter entering the ring. In addition to the likelihood that fighters will wake up the next morning feeling “punch-drunk” — the lingering aftereffects of a blow to the head that can feel like a particularly excruciating hangover — they run the risk of serious injury. Paskevicius recalls that following a 2014 match, his opponent was bent over the trash can “puking after the fight for the next hour.” Later, after his opponent left to get medical attention, Paskevicius checked in to see if he was all right: “He said, ‘Yeah, I just had some minor head trauma.’”

The danger comes when fighters — particularly inexperienced ones — don’t follow the rules. And Fight Night’s rookie participants regularly engage in dangerous techniques: Fighters have been known to hit each other in the back of the head, an illegal move due to its association with serious injury to the brain and spinal cord, which can lead to brain trauma, paralysis, and death. The 2021 Fight Night bouts were described by Edgar Soltero, an audience member who attended to support a friend, as “chaotic. A bunch of inexperienced fighters resorting to panic tactics. Turning around, doing a full 360, exposing the back of their heads.”

When properly supervised, boxing can be “one of the safest sports out there.” The danger comes when fighters don’t follow the rules

Typically, the referee training required to oversee an amateur match “takes at least a year,” McAtee says. Even then, the match can be stopped by not only the referee, but also three other people overseeing the match — the coach, the ringside doctor, and the referee judge. This is “built in for safety,” he says. But not in this case. Kappa Sigma’s Fight Night had none of these redundancies, according to the AG’s report and the lawsuit filed by the Valencia family.

Because Fight Night referees rarely abide by the rules of sanctioned fighting events, matches often look more like what Soltero calls “a bunch of street kids” brawling than a boxing fight. Michael Herman, who fought in UNLV’s 2019 Fight Night, says he kept seeing “kids getting hammer-fisted to the head. You have two opponents mauling each other, and no one knows what the fuck they’re doing.”

IN THE WEEKS before Fight Night, Nathan’s mother, Cynthia Valencia, begged her son — her youngest child — to drop out. “You worry too much. Focus on the positive,” she recalls him telling her. “This is for charity.” His fight had also been made the main event, something that was an honor — and a source of anxiety.

The fact that he’d signed up in the first place had been a surprise. Valencia, 20, wasn’t a student anyone had expected to participate in an event like this. In the past, he’d shown little interest in either martial arts or feuding with rival fraternities. His Sigma Alpha Epsilon brothers called him “a true gentleman.” He’d drive any of them across town at a moment’s notice, or hop on a late-night call to lend advice. He was also known to dote on Foster, his girlfriend of just under two years, a soft-spoken strawberry-blonde, who, like Valencia, studied kinesiology at UNLV. “The day I met him, I texted all my friends: ‘Guys! I’m gonna marry this man,’” she says. She, too, asked him to change his mind about the fight. “You don’t have to do this,” she told him. She remembers him shaking his head and saying, “No, I have to.”

Valencia had been training alongside another fraternity brother, Daniel Corona, at a local boxing gym, where he attended nine separate sessions over the course of a month, according to the AG’s report. Those consisted of lifting weights, jumping rope, and sparring with other members of the gym. “He was in perfect health,” says Corona. “He was never winded, unless we did cardio. He was in great shape.”

Valencia told friends that he was giving up drinking, vaping, and weed. Foster would later tell authorities that he complained of “severe headaches” following the practice matches, but medical experts would find no evidence of previous brain trauma.

Aleman, a finance major who DJ’d on the weekends, says that, like Valencia, he was drawn to the event by the charity aspect: “We’ve been doing this thing for 10 years,” says Aleman, who had worked Fight Night before, but never participated. “It was the biggest philanthropy event on campus. I wanted to do it for my fraternity.”

Aleman says he didn’t hit any special gyms, though he took it seriously enough to stay clean the month before the event. “I was entirely sober on all substances,” he says. “I wasn’t training professionally, but I was running a lot.”

Valencia and Aleman were both juniors, and despite being in rival fraternities, barely knew each other. They first met at a Kappa Sigma flag-football game a few days before the fight. “We introduced ourselves in public,” he says. There was no “bad blood.”

IN THE LEAD-UP to Fight Night, flyers are posted throughout campus, and students drop off their participation forms at the student union between classes. Student weigh-ins sometimes take place at the student union, and mock press conferences are, on occasion, hosted there, too.

Still, the university denies any involvement with the event. Any questions pertaining to Fight Night “should be directed to Kappa Sigma as it was an off-campus, non-university event,” UNLV’s director of campus affairs, Francis McCabe, told Rolling Stone. “UNLV has no authority to regulate off-campus student activities.”

In a statement, UNLV said that it “[extends] our deepest sympathy to the family and friends of Nathan Valencia. Nathan’s passing has also greatly impacted our university, and over the past year and a half, we have transparently reviewed our practices and implemented changes that will help prevent such a tragedy from occurring again. UNLV is no longer affiliated with the Kappa Sigma fraternity organization.” Additionally, UNLV said that it commissioned an independent review and implemented “nearly all of the 20 recommendations made by” the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators.

Technically, Fight Night was sponsored by the University of Nevada chapter of Kappa Sigma, which was itself officially connected to the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Yet Fight Night, despite being an amateur boxing match, fell in a legal gray area. Since it wasn’t a public event, the Nevada Athletic Commission, which oversees all unarmed combat in the state, didn’t have authority. Since it wasn’t a college sport, the university didn’t have to regulate it. Essentially, the fraternity was expected to oversee itself.

While three nurses were in attendance at the 2021 event, Kappa Sigma organizers did not arrange for EMTs to be present — a standard requirement for all amateur competitions in the state. And three students who participated in previous Fight Night events say that they couldn’t remember the presence of medical staff at the events in which they’d participated either. Aquino, the sorority member and former Fight Night participant, says that at one Fight Night, the only medical staffer in attendance she was aware of was a 24-year-old communications major whose medical résumé consisted of a single CPR course.

In the 2021 Fight Night, the referee, Chris Eisenhauer, stepped in at the last minute to oversee the matches after Kappa Sigma was unable to obtain a trained referee, according to three students and the attorney general’s report. Eisenhauer, who does not have any certified referee training, got involved with the event because he’s the older brother to someone in Kappa Sigma, two students tell Rolling Stone. (Eisenhauer, who is named in the Valencias’ lawsuit, did not respond to a request for comment.)

Six students who participated in UNLV Fight Nights say referees lacked experience and would let fights run crucial seconds longer than these participants believed they should have — a dangerous infraction in a lightning-fast sport where serious injury can be meted out in one bone-crunching blow.

In a 2014 fight, Mark Anthony Posner, the then-president of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, was knocked unconscious in the ring after his opponent elbowed him in the face. Posner fell to the ground, and when he came to, blood in his eyes, his opponent was crouched on top of him, “still swinging,” Posner says.

The referee called the fight, but Posner begged to continue, telling the ref, “I’m not gonna end it here,” he says. At Posner’s insistence, the ref let him fight additional rounds. In the end, he lost because he “couldn’t see” through the blood. His fight ended with a trip to the hospital. “My entire eyelid was completely split open,” he says.

In an MMA-style match during 2017’s Fight Night, a referee hesitated to call the fight as Phi Delta Theta fraternity brother Josh Bigham delivered blow after blow into his opponent’s skull. To Bigham, it seemed that his opponent could no longer defend himself, but he continued, thinking that “maybe the kid looked better to the ref than he did to me,” he says.

Eventually, Bigham says, this referee tapped on his shoulder, signaling the end of the fight. If Bigham had already sensed the referee’s inexperience, the shoulder tap was a dead giveaway: MMA referees signal the end of a fight by physical intervention, often using their body as a shield or using brute force to pry off the winning fighter. This ref was clueless; they all were. “We did not have legitimate referees. They didn’t know anything about fighting,” says Bigham, who participated in three Fight Nights over three years. Bigham can’t remember whether or not the other fighter’s nose was broken, but by the end of the fight “he was bleeding a lot out of it,” he says.

If there’s disorder in the ring, there’s pandemonium in the crowd, adding to the anarchy of Fight Night. Alcohol is plentiful at the events, despite the fact that many of the people there are underage. Fists fly in the crowd or in the parking lot before and after the event, but none of the students I spoke to could remember any security in attendance at events. “Everyone was trashed,” says Bigham. “They pregame for these events. There’s always a handful of people that fight in the parking lot beforehand.” At her own Fight Night, Aquino says, “people were screaming, drinks were flying, and alcohol was everywhere.”

One 2014 participant’s fight ended with a trip to the hospital. “My entire eyelid was completely split open,” he says

SOMETIME IN THE 10 minutes that Valencia and Aleman were in the ring, a blood vessel separated from Valencia’s skull, filling his brain with blood. Later, according to one individual familiar with the autopsy, Valencia was diagnosed with a rotational injury to the head that caused a subdural hematoma. Even if he survived surgery, he would always be in a vegetative state, the surgeon told Valencia’s mother at Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center the evening of the fight.

When Valencia died four days later, the coroner’s report would indicate that it was a direct result of blunt-force trauma to the head. While his death was ruled a homicide, it has not been classified a crime.

Valencia’s parents, Cynthia and John, have found no easy place to rest the blame for Nathan’s death. They have since filed a lawsuit against UNLV, Kappa Sigma National, the Sahara Events Center, where Fight Night was held, and the referee overseeing the match in hopes that both universities and fraternities will regulate similar events with increased scrutiny in the future. They accuse both UNLV and Kappa Sigma of having prior knowledge of injuries related to past events, and allege that Kappa Sigma neglected to ensure students’ safety, inspect gear, and hire qualified professionals to oversee the match. The suit alleges that the defendants are “in some manner negligently, vicariously, and/or statutorily responsible” for Valencia’s death. “It’s our hope that we can shed light on this tragic event with a sincere desire to create awareness to prevent this from ever happening to another family,” says the family’s attorney, Benjamin Cloward. (In legal filings in response to the suit, all of the defendants have denied the allegations.)

Besides Kappa Sigma’s UNLV suspension, in December 2021, the Nevada Athletic Commission passed “Nathan’s Law,” an emergency regulation requiring its oversight on any unarmed combat hosted by university-affiliated groups in the state.

Though Fight Night has been permanently banned from UNLV, charity boxing events are still held annually at universities throughout the country. In February 2022, a fraternity-sponsored event called “Boxing Weekend” was held again at the University of Tennessee after a four-year suspension. The 2018 event had been interrupted by the death of a student who collapsed in the ring from cardiac arrest after taking Adderall and caffeine before the fight.

IN THE WAKE of Valencia’s death, rumors about Aleman spread throughout campus. The attorney general’s report raised questions about his gloves, which went unexamined by both police officers and the attorney general’s office after the event. Several people close to Valencia told me they thought Aleman may have put a weighted object in his gloves in order to injure Valencia, a rumor lacking evidence. Others also whispered that he was intoxicated.

Both Aleman and Aleman’s family attorney, Sean Claggett, adamantly deny these allegations. They say Aleman was sober, and note that neither police nor the attorney general asked to examine his gloves. “There was nothing in the gloves,” Claggett says. “They were big, soft gloves, because no one was trying to hurt anyone. There is no question in my mind as to why Emmanual is not listed as a defendant in the lawsuit: It’s because he didn’t do anything wrong.”

Yet Lyn Julian, Aleman’s stepfather, understands why Valencia’s grieving loved ones suggested this: “If Emmanuel died, we would maybe be thinking the same thing.”

After Valencia was taken to the hospital, Aleman sent him a text: “Hey man hope you’re doing ok good fight brother! All love.” He went to visit Valencia the next day, but was asked to leave by Valencia’s friends. He didn’t attend the funeral. “I thought it would make it more about me than Nathan if I showed up,” he says.

In the months following Valencia’s death, Aleman fell into a depression. Several people close to Valencia reached out to Aleman on social media, telling him that Valencia’s death was his fault. Fellow students sent death threats along with screenshots of his family home. “Guess who knows where your mommy and daddy lives,” one student wrote. People have reached out to both his current employer and venues where he DJs, attempting to get him fired and saying he shouldn’t be hired after what happened.

As rumors swirled at UNLV’s campus, Aleman’s mental health deteriorated. He has suffered anxiety going out in public. “I don’t know what people’s opinions are when they see me,” he says.

The Alemans have not reached out to the Valencias because they were afraid their overtures would be unwanted. “We offer our condolences and would love to talk to the family,” Julian says. “We understand, because it could have happened to us.”

Months later, the Valencias are still reeling from the death of their son. On Mother’s Day 2022, Cynthia Valencia was in the bathroom getting ready when someone knocked on the door. Immediately, she thought it must be Nathan. But then, as she reached to open it, she stopped short, realizing suddenly that whoever was knocking was not Nathan, and would never be Nathan again.

For Cynthia, the world has been transformed into a minefield of grief. So many seemingly innocent things — words, names, places — can now deliver sudden emotional wounds. She cannot bear to hear the words “graduation” or “UNLV.” She will likely never return to the beaches of Southern California or Lake Tahoe, favorite family vacation spots.

“He was my world, you know?” she says.

“We are a broken family,” says Nathan’s father, John. In the months following his son’s death, John, a devout Catholic, has found himself doubting his faith in God. Now, he looks for signs of his son in everyday life. At one point during our conversation, he takes out his phone to show me a photo of a tapestry hanging in the living room: In the crushed folds of the fabric, he can see a face resembling Nathan’s. It is a small comfort to John, who sees it as confirmation of his son’s closeness.

John feels a pang of envy every time he sees a family of four. He dreads the spring, when Nathan’s scores of friends — those kids who were always huddled upstairs in Nathan’s bedroom playing video games or hanging out on the back patio — will graduate college.

John had thought that the passing of time might ease the unbearable weight of his grief, if only a little, but he perpetually finds himself pulled back to the bottomless well. Some days the pain is so acute, it is like losing Nathan all over again. As the one-year anniversary of Nathan’s death approached, the Valencias prepared a celebration of life at a nearby park, honoring Nathan’s memory. They have found it impossible to move forward because of the lawsuit, which requires that they regularly revisit the circumstances of his death. (The trial is set for May 2024.)

The Valencias have yet to touch anything in Nathan’s room or sell his car, which sits idle in the driveway. Foster still occasionally stops by the Valencia home. Sometimes she sits quietly in Nathan’s room, alone.

“The dirty clothes in Nathan’s room are still there. We’ve kept everything the exact same,” says John. “In our minds, he’ll come back.”