T

he 911 call came in around 2:30 p.m on April 4.

“Help, someone stabbed me,” said the voice on the phone.

Police and paramedics rushed to the address he gave near the downtown waterfront, beneath the hulking steel beams of the Bay Bridge. By the time first responders arrived at the 300 block of Main Street, the man who made the 911 call was lying bloody and unconscious on the sidewalk, his unmoving figure illuminated by the lights lining the doorway of a data-server company. He was a white man in black jeans, a black T-shirt, and a black jacket.

Emergency workers took him to nearby San Francisco General Hospital, where he was later pronounced dead, with a stab wound to the hip and two to the chest, including through the heart.

It was the 12th homicide of 2023 in San Francisco, a city with one of the lowest murder rates among big cities in the U.S. But this death stood out from the usual anonymity of victims who garner little more than a blurb in news coverage. From this victim’s wallet, investigators learned he was Bob Lee, a 43-year-old father of two teenagers and a well-known tech luminary who had revolutionized JavaScript coding and made his name as the creator of Cash App.

By sunrise, word of Lee’s death had spread far and wide, spurring a wave of social media posts from members of the tech sector who declared that such a violent crime was a symptom of what they saw as San Francisco’s intensifying lawlessness.

David Sacks, founder of Craft Ventures, said on a podcast that he would “bet dollars to dimes” that Lee was killed “for no reason by a psychotic homeless person.”

Elon Musk tweeted: “Violent crime in SF is horrific and even if attackers are caught, they are often released immediately.”

Venture capitalist Jason Calacanis blamed city officials, whom he described in an all-caps tweet as “Evil incompetent fools & grifters who accomplish nothing except enabling rampant violence.”

Then, nine days later, San Francisco police arrested a suspect who would be charged with murdering Lee.

Contrary to assumptions blasted across the internet, the defendant was not a robber nor a vagrant, but a fellow member of the local tech industry, Nima Momeni, a 38-year-old who ran an IT consultancy firm and knew Lee. As details of prosecutors’ allegations emerged over the following days, the story suddenly flipped from a cautionary tale reflecting San Francisco’s so-called doom loop to a sordid scandal that exposed the excesses of the fast-living tech scene, a parable on the pitfalls of indulgent drug use and loose sexual morals, a dark turning point in a once-soaring industry now stumbling through layoffs, scams, delusions, and the crashing dreams of ambitious young entrepreneurs who poured into America’s golden boomtown.

The weight of a city’s complicated and entrenched problems fell onto two men drawn to the same place from opposite corners of the world, driven by parallel hopes, colliding in a burst of unimaginable violence.

But behind the efforts seeking to project deeper meaning behind the tragic killing lay the simple question at the center of the case: Why did Momeni kill Lee?

Over the past six months, in conversations with more than a dozen people, including those close to both men and those involved in the investigation, it’s the question I sought to answer.

Everyone was important to Lee, everyone was special. It didn’t matter who.

There were multiple memorials for Lee, who attended Burning Man regularly — one in Miami, where he lived his final year, and one in San Francisco.

COURTESY OF THE LEE FAMILY

Lee had multiple memorials. One, on April 23, was in Miami, where he lived his final year. Another, on May 5, was in San Francisco, where he lived most of his adult life. Both presented a distinct sense of Lee’s reputation among those who had crossed paths with him.

In a tech scene filled with “guys running around with enormous egos, Bob did not have an ego,” says Rick Teed, a 63-year-old real estate agent who was friends with Lee. “Everybody was important to him, everyone was special; it didn’t matter who it was. That’s why there was such an outpouring of love.”

At the Miami memorial, around three dozen people gathered at a house, mostly strangers to one another until they shared stories about how they’d met Lee. A projector beamed photos onto the walls. A shrine arose, piled high with items that reminded friends of Lee, including pieces of clothing and brightly colored art.

“Some of the people who knew him for longer from San Francisco were like, ‘I don’t even know half the people here,’ ” says Lauren Weiniger, a health-tech entrepreneur who met Lee in 2017 at South by Southwest and attended both memorials. “People assumed, ‘I really love Bob, but the others must have been using him for his money.’ But everyone was so close by the end [of the memorial] because we all realized that every single person there loved Bob.”

At the San Francisco memorial, more than a hundred people gathered inside the waterfront Ferry Building. Beneath high ceilings and amid servers circulating hors d’oeuvres, guests took selfies with a life-size image of Lee and contributed relics into a box that his friends would set aflame at Burning Man, which Lee often attended — “a cathartic and healing concept that he would have really loved,” Weiniger says.

Both memorials concluded with music from a live DJ. To his friends, there was no more fitting way to celebrate Lee.

With blue eyes below close-cropped brown hair, a clean shave on a square jaw, and an easygoing drawl, Lee seemed a living embodiment of Midwestern sensibilities. He grew up in St. Louis, where his competitive intensity on the high school water-polo team earned him the nickname “Crazy Bob,” a moniker he’d keep for the rest of his life, including as his Twitter handle. He came of age at the dawn of the digital revolution and set his sights on the tech industry by the time he reached college. He majored in computer science at Southeast Missouri State, then worked as a consultant for companies including AT&T and Edward Jones, and he co-wrote two books about coding while still in his early twenties. In his spare time, he wrote a computer program to defend Microsoft servers against the Code Red computer virus, then gave it away for free. “He had an overarching need to make technology accessible and to help out everyone,” his family said in a statement after his death. “Bob’s dream was to make technology free and available.”

One night, walking past a bar in St. Louis, he glanced through the window and saw a woman he had to meet. He asked the bartender what wine she was drinking, then ordered a bottle for her table and introduced himself. Krista Drake, a journalism major who had pivoted to dental ceramics, was unimpressed. But her sister took down Lee’s number and persuaded her to give him a chance. A week later, they went on a date at an elegant bar where they tasted ports, smoked cigars, and discovered they shared an exuberant energy that left them with the sense that they’d each met their match. “The conversation never lulled,” Krista says. “It was beautiful.”

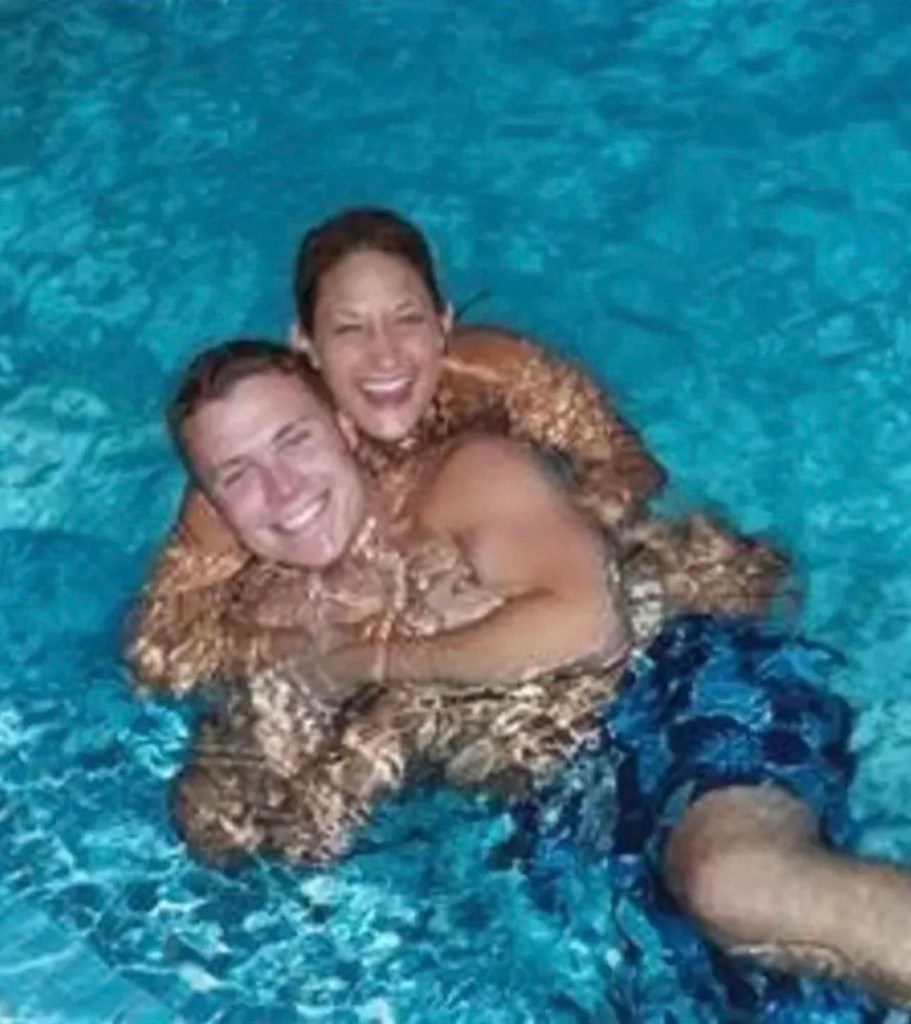

Lee and his ex Krista remained close after divorce. After moving to Miami, he’d return to San Francisco to visit her and their two children.

COURTESY OF THE LEE FAMILY

In 2004, shortly after they started dating, Lee got a job at Google and moved to Silicon Valley. Around then, Krista got a job at a lab a few hours away, and the couple maintained a casual semi-long-distance relationship. They were both 24 when Krista got pregnant. “At that age, you get pregnant, it’s scary,” she says. “But he made it into a fairy tale of ‘Our lives are just beginning.’ He said, ‘We can do this. I’ll make enough money. You can be a stay-at-home mom.’ ”

Together, they moved into an apartment in San Francisco, got married, had a second child, and then bought a house near Google’s campus in Mountain View. In California, Lee found himself among a competitive generation of software engineers landing in the wake of the dot-com bust with ambitions to build digital empires over the old wreckage. Through their mutual connection to St. Louis, Lee befriended Jack Dorsey, who tried to hire him to help develop the new social media platform he was building — Twitter. Lee turned him down. “You can’t afford me,” he said, only half joking, according to Krista. Lee quickly made a name for himself helping to develop the Android Operating System and streamlining Google’s advertising platform.

Two years later, Dorsey made another run at Lee, poaching him to eventually serve as the first chief technology officer of Square, a digital-commerce app he’d founded. TechCrunch called the hire “quite the catch.”

Unlike the more widely known industry figures splashed into headlines and press releases, Lee earned his reputation behind the scenes, focusing on the nitty-gritty coding challenges that separated a good idea from a good product. In his early years at Square, he built the program that would define his professional legacy: Cash App, a mobile payment system that within a decade was handling 70 million transactions a year and earning more than $1 billion in annual profits. In 2014, a year after the app was launched, with Square’s initial public offering on the horizon, Lee left the company with enough wealth to pivot to investing, planting stakes in the social network Clubhouse and Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Around then, Lee and Krista bought a $1 million penthouse apartment. With a shared appreciation for late nights with new friends, the couple became a staple on the city’s social circuit, forging a reputation for the fun-loving spirit they brought to the happy-hour mixers, dinner parties, and club outings that filled their calendar.

A few years later, they divorced. It was an amicable parting, Krista says. When people asked them why they separated, “we would laugh and say, ‘because we love each other,’ ” she says. “I was meant for more than being a stay-at-home wife and mother, and he saw that.”

Lee moved into a penthouse in San Francisco’s Mission Bay neighborhood, and Krista and the kids settled into a house north of the city. Nearly every weekend Lee joined them for family dinners, and Lee and Krista introduced each other to the people they dated. She remained among his most trusted confidants in a city brimming with people seeking to enter his orbit. “When we’d go out, there was always somebody who wanted to talk to him,” Krista says.

With his niche celebrity burgeoning within the tech scene, Lee was never short of business suitors, hangers-on seeking success by association, and new acquaintances eager to exchange phone numbers and LinkedIn connections. But, his friends say, what distinguished Lee from other tech bigwigs was that he navigated his crowd of admirers with the jovial attentiveness of a politician campaigning for votes, as if it was him trying to win their affection rather than the other way around.

“He was one of the most generous and selfless leaders that I knew,” says Harper Reed, a tech entrepreneur who worked as CTO of Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign and met Lee at a conference around 2010.

Lee (center), with two friends, was known as a regular on the tech party circuit, frequently celebrated for its “work hard, play hard” ethos.

COURTESY OF THE LEE FAMILY

Lee was accessible, frequenting tech conferences, launch parties, and other events that tended to draw those hoping to rub shoulders with the Bay Area’s most prominent disrupters. To get face time with Lee, though, a prospective associate had to be willing to stay out late. Lee was known to work long hours, then let loose afterward in the neon lights and thumping bass at venues across the city’s SoMa and Marina neighborhoods. Lee routinely astounded friends with his stamina, which somehow seemed to never wane as he balanced high-stakes professional obligations with a voracious appetite for good times. Teed recalls nights when he’d leave a party after midnight, only to run into Lee on his way in after a long day of work.

“The guy was going 18, 20 hours every day, highly functioning,” Teed says.

While Lee was widely known for his energetic positivity, those closest to him were aware that below the surface, he battled depression. One thing that helped him ease that interior turmoil, -Krista says, was ketamine, a sedative substance that washed away the concerns roiling his mind.

Over his decade living in the Bay Area, Lee made pilgrimages to Burning Man, Coachella, and South by Southwest. He danced at raves. He and Krista were regulars at the Battery, an exclusive social club that only accepts applicants endorsed by current members and which charges $2,800 in annual dues. Most of Lee’s friends who spoke to me met him somewhere along the tech-industry event circuit that blurs together networking, dealmaking, and partying.

“There were so many tech parties,” Teed says. “Everybody kind of knows everybody. Anytime there was a tech launch or a new luxury-building launch, you’d get all these tech guys coming through.”

People crossed paths with a constant, kinetic energy that clouded memories of introductions. Strangers became fast friends, outsiders fused into the community, social circles tangled into a knot. Among the familiar faces in this scene was Khazar Momeni, a 37-year-old who lived downtown and met Lee at the Battery.

Lee’s friends who spoke to me say they didn’t know who drew them together, whether they were introduced or connected spontaneously, but two friends estimated that Momeni and Lee began occasionally partying together within the past few years.

At some point, Khazar introduced him to her brother, Nima.

With a growing interest in crypto, Lee began spending more time in Miami. He was an early investor in MobileCoin, a blockchain exchange founded in 2017, and in December 2021, Lee was named the company’s chief product officer. Weiniger, who had lived in Miami for years, recalls Lee falling in love with the city, which boasted the entrepreneurial spirit reminiscent of what drew him to San Francisco. “It’s got this new emerging innovation feeling,” she says. “A lot of people who were there he knew from San Francisco.

In July 2022, Lee moved with his father to Miami’s Edgewater neighborhood, where they settled into a $9,000-a-month apartment with a pool, a hot tub, and a wraparound balcony with a panoramic view of Biscayne Bay. But San Francisco remained a regular part of his life. His kids and ex-wife lived in the Bay Area, as did many of his oldest friends. He visited monthly.

In March, he arrived in the city to watch his daughter star in her eighth-grade play, High School Musical. He stayed at the 1 Hotel on the Embarcadero waterfront.

In the summer of 2020, Nima Momeni moved into a condo in Emeryville, just over the Bay Bridge from San Francisco. Part of a sleek brick-and-iron two-story building that had been converted from an old warehouse, the home doubled as an office for his IT consulting firm. The 1,700-square-foot loft had big windows and a spiral staircase. A pool table filled the space between the couch and the kitchen. Several guitars stood on a rack next to a desk stacked with books that included Albert Camus’ The Stranger. Art on the walls featured phrases in Farsi.

To his neighbors, Momeni bore the markers of an upwardly mobile entrepreneur who had risen through the ranks of the startup scene. “Probably how everybody imagines a typical Bay Area tech consultant,” says Sam Singer, a public relations executive who lives in the building.

Momeni owned a fancy convertible and a boat. He ran a self-made enterprise successful enough to pay the bills. He spent time at Burning Man and DJ’d parties he threw at his home. He donated to Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign in 2016, then to Donald Trump’s in 2020.

After Chris Donatiello moved into the complex in March 2020, he occasionally encountered Momeni, usually running into him in the parking lot where Momeni kept his BMW. They never exchanged more than small talk, but Donatiello recalled his neighbor fondly. “Being in a new place, you’re open to making any friend you can,” says Donatiello, who is 52 and works in sales. “He was a guy roughly my age, very upbeat and positive.”

Then one morning, at around 5:30 a.m. on April 13, a loud bullhorn and flashing blue lights awakened Donatiello. Out his window he saw police cars. Donatiello assumed the cops were there for a catalytic-converter theft because there had been a rash of them in the area. He went back to sleep, and when he woke up a few hours later, he learned of the real reason from the building’s Facebook group, which posted an article from San Francisco outlet Mission Local breaking the news that Momeni had been arrested on charges that he murdered Bob Lee. Donatiello and Singer both told me that they had trouble reconciling the news with their impressions of a neighbor who struck them as harmless.

“I’m shocked by the allegations because he seemed like a very nice guy,” Singer says.

Nima Momeni (left) was charged with Lee’s murder (he pleaded not guilty). Momeni was close to

his sister, Khazar (right), who knew Lee as well.

COURTESY OF THE MOMENI FAMILY

Momeni projected an image that didn’t always match reality. His LinkedIn page showed that he had completed an associate’s degree at Laney College, then enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley. But one of the lawyers Momeni hired, Paula Canny, told me he never graduated from Laney, and his only association with UC Berkeley was for an affiliated certificate program. Those deceptions on his résumé veiled a professional ascent that, in reality, embodied the do-it-yourself hustle at the heart of Silicon Valley’s mythology. Momeni was born in Iran. His father was a dentist, his mother a homemaker with a college degree, Canny says. In a statement to the court for her son’s arraignment, Mahnaz Momeni said she and her children “had endured years of abuse and violence at the hands of my husband.” When Momeni was 14 and his sister, Khazar, 13, their mother fled Iran with them, first to Paris, then to Berlin, both cities where she had relatives. But she wanted to go to a country where her husband couldn’t easily follow them, so she and her children flew to the U.S. with a tourist visa, then applied for asylum, according to Canny. They settled in the East Bay, where a friend of hers lived.

Upon arriving in the U.S., their mother got a job at a flower shop and the Momeni siblings attended Albany High School, which is locally known for its strong academics. In statements to the court, Khazar described her brother as “protective of her,” and their mother said Nima “took on the role of caretaker” for the family.

Momeni’s lawyers declined to make him or Khazar available for an interview. But according to Canny and statements to the court from people who knew Momeni, he developed an interest in computers when he was young and taught himself to code. According to Canny and Momeni’s LinkedIn profile, he began his career as a systems engineer and IT administrator at a series of companies, before starting his own in 2010, Expand IT, a consultancy firm that eventually broadened to employ several contractors. He lived in San Jose and spent his days helping small businesses set up their computer hardware and internet infrastructure. Momeni’s financial support helped his mother enroll in dental-hygienist school, Canny says. One year, Momeni and Khazar gifted their mother a BMW for her birthday.

Momeni’s trajectory seemed to reflect a smooth ascent toward professional stability, cloaking the personal turmoil that would tumble into public view after his arrest for Lee’s killing. From the outside, he represented an example of the upward mobility available to those savvy enough to find a niche in the tech boom.

In 2014, Momeni made it into San Francisco. He rented an office space in a low-slung -converted Navy building with chipping peach paint and cement hallways on Treasure Island, an artificial landmass in the middle of the bay.

Even as his business endeavors progressed, Momeni stayed on the periphery of the city’s party circuit, confining his social life to gatherings with close friends at his home or at music festivals. His company had a San Francisco business address, but a bridge still separated him from the pulsing heart of the tech boom. Looking west from the dirt parking lot out front unfurled a view of the famous skyline, growing richer every year with new towers disappearing into the fog.

Khazar Momeni occasionally partied with Lee over the past few years, and she and a friend were with Lee and his friend the night he died.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Momeni’s sister, Khazar, and her husband, Dino Elyassnia, a plastic surgeon with more than 57,000 followers on Instagram, lived high on that skyline, behind the black-tinted windows of the Millennium Tower, a $350 million 58-story colossus that looked impressive but was haphazardly constructed. Its foundation left it sinking 18 inches within a decade of opening in 2009, turning it into a satirical symbol of a tech boom premised on the Mark Zuckerberg ideal of moving fast and breaking things.

While Momeni hovered along the fringes of San Francisco’s downtown scene, his sister dived in, dancing through lively nights with a glamorous air and high-fashion wardrobe. “If there was a Real Housewives of San Francisco, she would have a leading role,” says Saam Zangeneh, one of the lawyers Momeni hired. Khazar joined the Battery and frequented many of the same raves as Lee and his friends. When Khazar needed someone to pick her up during a late night, she often called Momeni, Canny says.

Lee’s friends I spoke to didn’t remember much about the Momeni siblings. “He had met her somewhat recently,” Weiniger says. Krista says she encountered Khazar once, in passing, when she picked up Lee from a party at Khazar’s apartment. Krista knew all of Lee’s close friends and met all of his girlfriends, and Khazar was neither, she says. “They weren’t on my radar,” she says of the siblings. “They were definitely newer acquaintances.”

In the days and weeks after Nima’s arrest, Lee’s relationship with the Momenis emerged as a central element in the mystery over the circumstances of his death, sliding a public microscope over the sort of details people tend to keep discreet. Prosecutors stated that Khazar’s marriage was “in jeopardy.” A Wall Street Journal article reported that Khazar and Lee were enthusiastic participants in a party scene that included heavy drug use and free-spirited sexual encounters. A toxicology report showed that Lee had cocaine and ketamine in his system when he died.

“The reality is the tech industry is deep in using drugs.”

The high-profile homicide exposed a lifestyle commonly shared among the young and indulgent in the city’s privileged class. Late nights of dancing, drugs, and sex are “embedded in the culture,” Weiniger says of the tech scene. Several members of the city’s finance and tech sectors describe to me the lure of a nightlife circuit where access to drugs comes easily and casually. Those with money can purchase cocaine to boost waning energy levels, MDMA to melt into the ecstatic trance of a crowd, psilocybin to unlock doors of creative perception, Adderall to lock into focus, Xanax to dull anxieties, and ketamine to wipe everything away.

To Chesa Boudin, the district attorney ousted in a 2022 recall, an important point to draw from all the details emanating from the Lee murder case is how it reflects the stark disparity between who is and isn’t allowed to break the law, in San Francisco and across America. “There’s this sort of insistence among conservatives in this city that it’s only poor scary people who are doing drugs,” says Boudin, who noted the country’s history of punishing crack-cocaine use more harshly than the more expensive powder version. “The reality is the tech industry is deep in using drugs.”

Lee, however, wasn’t reckless in his drug use, friends say. “There was so much more to him than party-boy Bob,” says Krista. “Yes, we have taken drugs before. Yes, he has done this, that, and the other, but there was always a time for it.… Family came first. His career came second. He would never do anything to jeopardize that.”

On the afternoon of April 3, Lee brought Khazar and other friends to the sleek glass downtown apartment of Jeremy Boivin, a 34-year-old sales executive who had twice been convicted of possessing drugs with intent to sell. Lee and Boivin had known each other for a few years, traveled internationally together, and celebrated holidays together at Lee’s house. The hours that followed would become central in the investigation into Lee’s killing.

Police, including a SWAT team, arrived at Momeni’s home early on the morning of April 13 prepared for armed resistance. “We didn’t serve the warrant for several days, not because we didn’t know who the prime suspect was, but because a high-risk search warrant is planned out very carefully,” says a law-enforcement source with knowledge of the case who requested anonymity because they weren’t authorized to discuss it. “We heard from several people that he was big into knives” and possibly “infatuated with firearms.” Momeni surrendered without incident.

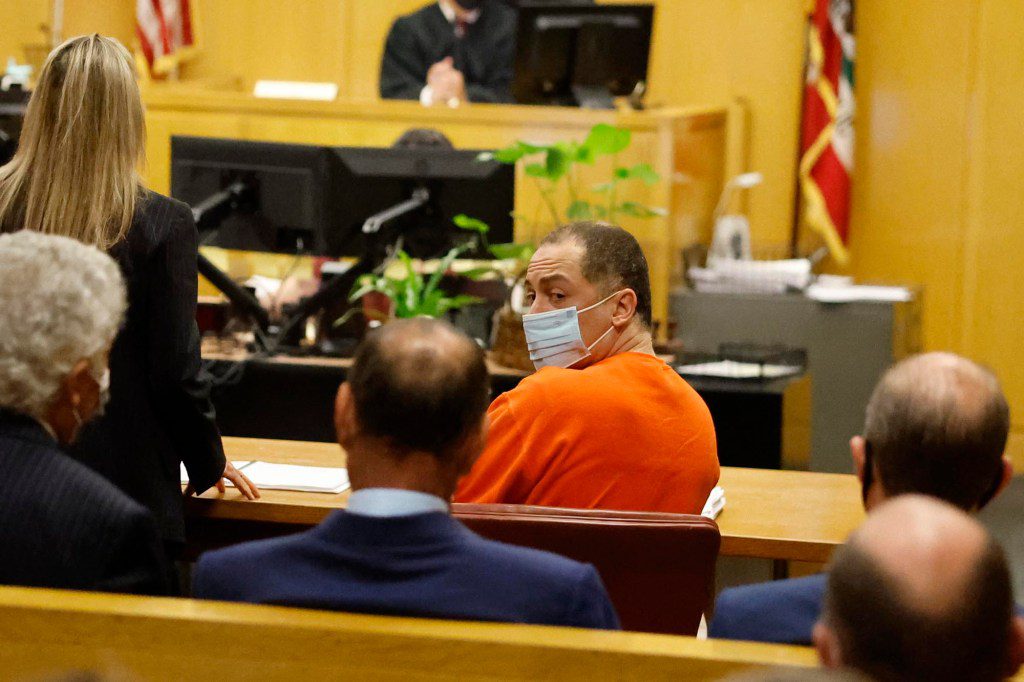

Nima Momeni, right, in court at the Hall of Justice on May 18, 2023 in San Francisco, California.

Paul Kuroda-Pool/Getty Images

In the days after Momeni’s arrest, details from his backstory unfolded in a series of news articles describing a track record of alleged violent and troubling behavior. Momeni had been arrested for domestic battery in August 2022 after a woman told police that he grabbed her arm and pushed her, according to an incident report first revealed by the San Francisco Chronicle, but the charges were dropped. The Daily Beast quoted an anonymous neighbor of Momeni’s who said that he was “super into weapons” — an assertion Canny bolstered by acknowledging in court documents that he kept a long “Crocodile Dundee knife” next to the driver’s seat in his car. The news stories described Momeni as a hothead with a quick temper and an appetite for cocaine. (His lawyer at the time told reporters that Momeni is “a contemplative, thoughtful person, not a degenerate maniac, which is how he’s being portrayed.”)

An array of surveillance footage tracked his movements on the night Lee died. At around 8:30 p.m. on April 3, he went to his sister’s apartment. Around four hours later, Lee joined them. Momeni confronted Lee about whether Khazar had done anything “inappropriate,” according to a police statement from a person anonymously referred to as “Witness 1” in court documents.

Text messages from Lee’s phone suggested that he and Momeni got into an argument. After the two men left the apartment at around 2 a.m., Khazar texted Lee: “Just wanted to make sure your doing ok Cause I know nima came wayyyyyy down hard on you And thank you for being such a classy man handling it with class Love you Selfish pricks.”

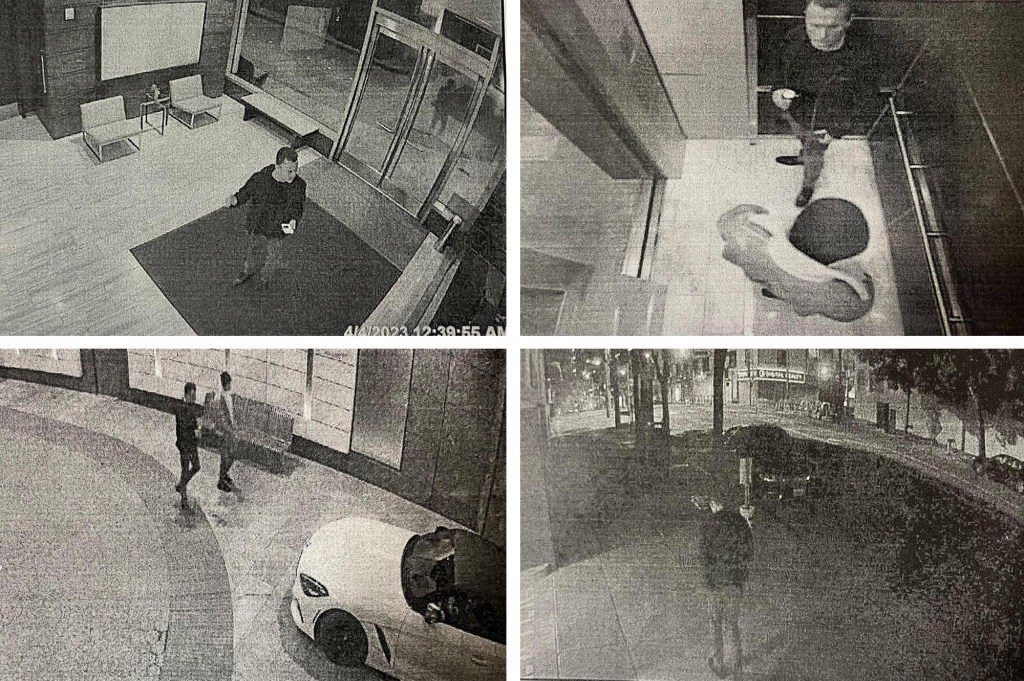

The building’s security cameras captured Lee and Momeni taking the elevator down together, then getting into Momeni’s white BMW. Cameras on other buildings showed the car driving a few blocks, then stopping near the intersection of Main and Bryant streets, beneath the Bay Bridge. The two men got out of the car, briefly stepping out of the camera’s frame. Then one of them got back into the car and drove off, while the other walked away. Cameras from other nearby buildings showed Lee stumbling up the sidewalk, trying to hail a passing car, before collapsing.

Security camera footage from the morning of Lee’s death shows him entering an apartment building and later getting into an elevator with Nima Momeni; then Lee and Momeni walking together, and then it captures Lee alone after getting out of a car with Momeni.

AN FRANCISCO PROSECUTORS’ OFFICE, 4

A few blocks from where Lee had exited the BMW, investigators found a paring knife that had Momeni’s DNA on the handle and Lee’s on the blade; prosecutors say it matched the brand of cutlery that Khazar had in her condo.

The case played out under the bright spotlight of international media coverage. Two dozen reporters, including two from Iran, packed into the courtroom for Momeni’s arraignment on May 18. The courtroom was so tight that other defendants scheduled to appear for arraignments that morning were asked by bailiffs to wait outside while Momeni’s high-profile hearing took place.

Khazar sat near the front in big sunglasses, alongside her mother and other loved ones. Momeni walked in with his wrists shackled, wearing an orange jumpsuit. As the prosecutor presented his argument, Momeni shook his head, his arms crossed at his chest. As Canny questioned the evidence against her client, a few supporters on Lee’s side of the aisle let out anguished sighs and wiped tears from their eyes.

Momeni was denied bail.

Less than a month after that hearing, Canny arrived at the jail to speak with him about the case. He declined to meet with her, she says. Afterward, she withdrew from the case. Now, Momeni has new legal representation, led by criminal-defense attorney Saam Zangeneh.

Canny says she doesn’t miss the stress of the case. Before Momeni had even issued his not-guilty plea in court, he’d become, in her words, “the most vilified person in San Francisco.”

Zangeneh has not explicitly refuted — nor conceded — that Momeni killed Lee. In interviews, he told me that he plans to examine the circumstances that drew the two men together on that night.

“I don’t think he was mad at Bob,” Zangeneh says. “I think he was disappointed with Bob for leaving his sister with Jeremy.”

Jeremy Boivin grew up in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he was president of his high school class and a running back on the varsity football team. After graduating college in 2011, he moved to San Francisco, to embark on a career in tech. After launching a company boasting an algorithm to help clients assess their property values, he worked in sales and data analytics before starting another company, which sold crystals and bath salts, according to court records.

He met Lee through mutual friends in 2019, and in early 2020, he was among a group that joined Lee on a monthlong trip to Tulum, Mexico. In a statement through his lawyer, Boivin said Lee “was a cherished personal friend who not only offered unwavering support but also served as a wise confidant in times of need.”

In an interview with me, Canny accused Boivin of supplying Lee with drugs. Boivin’s lawyer, Valery Nechay, says he was never a drug dealer: “He has not and does not presently sell any drugs to anyone.” But twice since 2020 he has been convicted of possessing drugs with intent to sell.

He has also faced more serious allegations.

In August 2020, he was arrested for allegedly raping a woman while she was unconscious in his apartment. He was charged with seven sexual-assault counts, along with counts for possession of drugs including GHB, cocaine, meth, MDMA, and ketamine. He pleaded not guilty to all charges. (His lawyer tells me it was a “consensual interaction.”)

Boivin was released after making bail, which was set at $200,000. According to the testimony of San Francisco Police Department Sgt. Brent Dittmer, it was Lee who paid it. (Boivin’s criminal-justice attorney denies Lee paid the bail.)

While out on bond, Boivin was arrested again, in September 2021, for possession of drugs including MDMA, LSD, Adderall, psilocybin, one kilogram of cocaine, and one kilogram of meth. He pleaded guilty in that case to a count of possessing MDMA with intent to sell and was sentenced to 10 months in jail and two years of probation.

Then, in March 2022, prosecutors under District Attorney Boudin dismissed the sexual-assault charges and agreed to a deal in which Boivin pleaded guilty to possessing MDMA and ketamine with intent to sell. He was required to complete a drug-treatment program, and the court ordered him to stay away from the woman. Nechay, Boivin’s lawyer, says the sexual-assault charges were dismissed “because they were fabricated by a party that was not credible.”

Months later, in August, Boivin was arrested a third time, for alleged possession of drugs, including heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. He was out on bail, with the latest drug charges pending, when Lee and Khazar visited his apartment on the afternoon of April 3. Two others joined them: Lee’s friend, a DJ who had just moved to the city, and a friend of Khazar’s whose name hasn’t been disclosed.

Khazar’s friend told investigators that Lee and his DJ friend left in the early evening, according to Dittmer, the lead investigator on the case, who testified at an August hearing. Then Khazar and her friend took three hits of GHB and passed out. When the friend woke, she found Khazar crying and half-dressed. The friend called Momeni, who arrived with Elyassnia to take Khazar home.

According to Zangeneh, Khazar “woke up, or gained consciousness, and was very rattled,” but at no point did she say that she had been sexually assaulted, telling her brother and husband “that nothing bad happened.” Momeni didn’t seem convinced. He FaceTime’d Lee, who was back at his hotel with the DJ friend, to question him about Boivin. Zangeneh declined to comment on whether Momeni knew anything about Boivin’s past at that point — “because that may or may not open the door to what our defense is gonna be,” he says.

When Momeni and Khazar were back at her place that evening, Boivin came over to speak with them, according to Dittmer, who said he learned the information third-hand, from Lee’s ex-wife Krista, who told him she had spoken with Boivin. In his testimony, Dittmer conveyed Krista’s account of what Boivin had told her: “Mr. Momeni was behaving in a threatening manner and saying, ‘Fuck you, I’ll kill you.’ ” Boivin left the apartment. (Krista confirmed this account in an interview with me, as well.)

Later that night, Lee arrived.

Shortly after I reached out to his lawyer for comment this summer, Boivin texts me and agrees to an interview. We meet at a restaurant near his apartment. He wears a fleece sweater and jeans. He brings a friend for moral support.

Boivin says that he has never sold drugs and that the woman who accused him of rape in 2020 made up the allegation because he wouldn’t loan her money she asked for. He says he’d never met Khazar before that day Lee brought her to his apartment. He says nobody at his place did drugs that day.

He denies that he pursued any sexual acts with Khazar or caused her any harm. He says the two women left his apartment in good spirits at around 7 p.m. To support this point, he says that later that night, around 3 a.m., half an hour after Lee and Momeni had left the Millennium Tower, Khazar called him and he came over to her apartment. He says they hung out until sunrise talking, though he says he can’t recall the details of their conversation. At that point, he says, neither of them knew Lee was dead.

“There are good days and there are bad days. There are still mornings I wake up and think this is all a bad dream.”

Flowers and cards left as people paying tribute to Bob Lee near the Portside apartment building in San Francisco.

Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Lee was supposed to meet Krista and the kids for coffee before heading to the airport for his flight to Miami on April 4. The family intended to discuss plans for the younger child to attend high school in Miami and live with Lee.

That morning, Krista awoke to two missed calls from Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, but when she called back, she was told it may have just been an automated call about an appointment. When Lee still hadn’t called her by 10, she checked the location on his phone and saw that it was at a police station. Maybe he’d lost it and that was why he wasn’t picking up. A friend who was supposed to drive him to the airport went to the police station. Sgt. Ditmer told him Lee’s family should go to the hospital. A doctor met them in a waiting room.

“I’m thinking he got beat up, he got mugged,” Krista says. “Worst-case scenarios were going through my head, but not the scenario we got.”

The kids were back from school when Krista returned home. They cried together the rest of that day. The weeks since haven’t been much easier. “There are good days and there are bad days,” Krista says. “There are still mornings I wake up and think this is all just a bad dream.”

A trial date has yet to be set. Momeni remains in jail. Court hearings continue to reveal more details about the case. Each twist in the story of Lee’s killing unraveled clues about what it was all supposed to say about the city he loved. Behind the sensational details lie the most unsettling possibility of all: that there was no grand message, only the bleak finality of a sudden death.

“That’s the hardest part,” Weiniger says. “That Bob is so in control and so larger-than-life that it doesn’t compute with our sense of right and wrong that something this random and senseless and stupid would be how it ends. I don’t know, the lesson is just life is fucking short.”

On Labor Day weekend, Lee’s loved ones congregated in St. Louis. That Sunday, they placed his ashes in a mausoleum beside his mother and held a memorial for him at the City Museum. At the center of the museum is a 10-story spiral slide that Lee used to zoom down with the kids.

“We like to remember all the good times,” Krista says. “We know from the bottom of our hearts that Bob would not want us to be sad.”