Immanuel Wilkins is visiting his hometown of Philadelphia. Shhh. Don’t tell his folks.

“I’m actually at my partner’s house right now,” he says on a video call. “I’m chilling out. I’m hiding from my parents.”

More from Spin:

- Wild Rivers Roll On

- To Hell With the Devil: Stryper’s 40-Year Reign in Christian Metal

- 2024 Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame Induction: Five Highlights

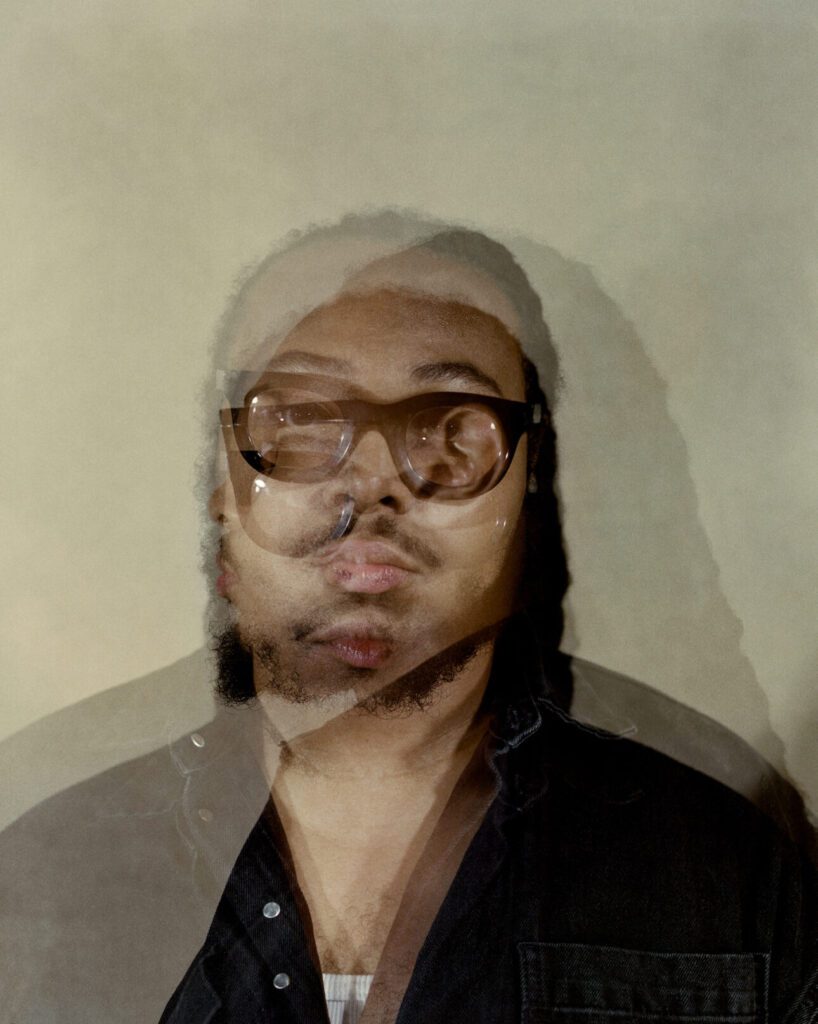

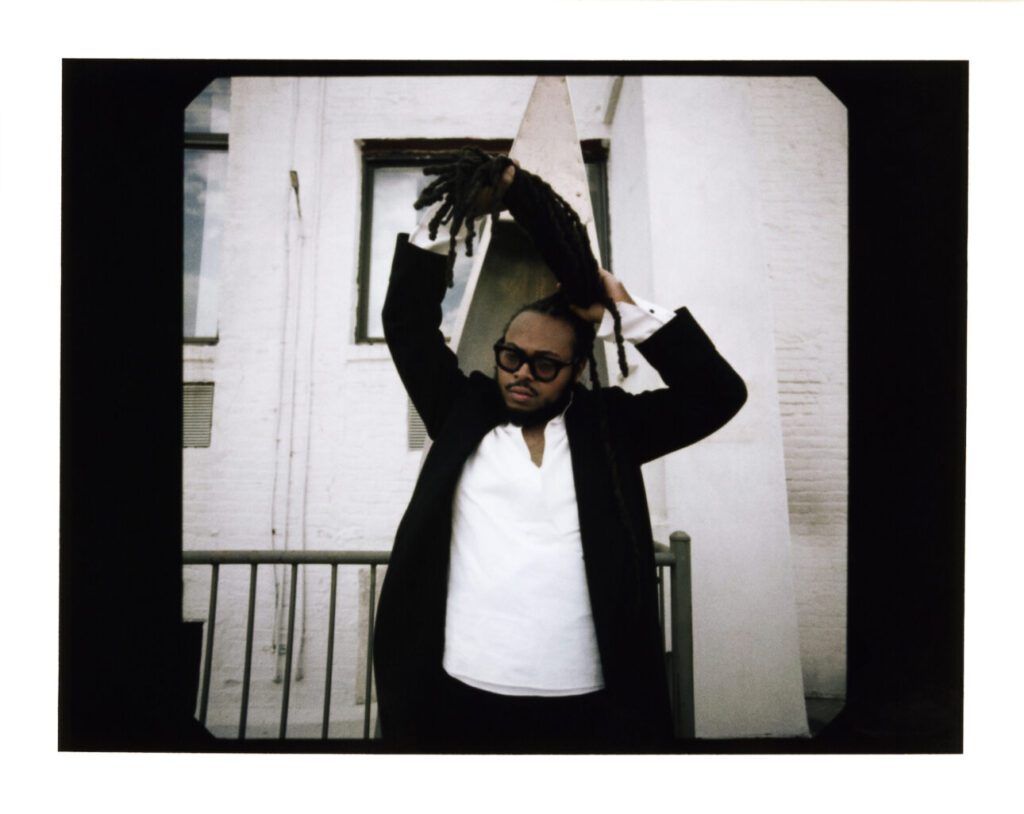

Quickly the young alto sax player, his new album Blue Blood affirming his stature as one of the rising stars of jazz, an astonishing leap from the already-brilliant work of his first two albums, realizes how that sounds.

“No, no, no, no, no!” he says, sputtering.

He’s not really hiding. He visited them the week before. He’s just on a quick trip to be with his partner for a day before heading back to his current home in New York and wanted them to have time to themselves. He loves his parents, he stresses. They bought him his first album (James Brown) and encouraged his music passions, first playing at church, then at the noted Philadelphia Clef Club’s youth jazz education program (Questlove is among its alums) and then packed him off to Juilliard.

From there he’s made his name with his own two albums leading his quartet, 2020’s Omega and 2022’s The 7th Hand, growing status as a go-to sideman for vibrant artists from young experimental trombonist Kalia Vandever (a Juilliard friend) to 80-year-old pianist Kenny Barron (working with him one of his goals in moving to NYC) and as a key figure in the famed Blue Note label’s repertory crew alongside drummer Jonathan Blake, vibraphonist Joel Ross and others. His family support made all that possible.

Oh! He almost forgot: “All of the music on Blues Blood was written in Philly,” he says.

That was during the pandemic, while he was holed up with his family. The album’s a remarkable work, his first with vocalists—Miami-rooted neo-folkie June McDoom (who also wrote most of the album’s lyrics), South India-raised Ganavya, activist-artist Yaw Agyeman and genre-busting Cécile McLorin Salvant—exploring deep cultural and emotional territory. The music moves from inventive, engaging art song to smoldering improvisations in which Wilkins and his bandmates—anchored by his regular colleagues Micah Thomas on piano, Rick Rosato on bass and Kweku Sumbry on drums—push to the outer limits.

It originated as a multimedia presentation, Blues Blood/Black Future, commissioned by and premiered at Brooklyn’s Roulette arts complex in 2021, inspired by the life of Daniel Hamm, one of the Harlem Six teens falsely accused and tried of murder in 1965. It’s not a literal telling of that story, but jumps from that in various explorations of themes related to Hamm’s experience and the long history of cultural tragedies and profound, lingering wounds before and after. Inspiration also came from author Christina Sharpe, who has written about the notion of generational memory and did the album’s liner notes, as well as sculptor-installation artist Theaster Gates, with whom Wilkins has played in performances of the Black Monks blues-gospel ensemble.

“When I was making this, what I was thinking about was, ‘Is it possible to make an immaterial archive?’” Wilkins says. “Is it possible to make a work that’s done on stage, or just in living, through oral traditions, or maybe just on a quantum level, like thinking about maybe the [New York jazz club] Village Vanguard and that when people walk in there they’re like, ‘Man, something’s in the walls.’ Archives that maybe don’t have a physicality. I was wondering if it was possible for me to facilitate a space for eight people to gather and just cook, you know what I mean? And by cook I mean that figuratively and literally.”

Yes, literally. There was a chef cooking on stage during the Roulette shows. Of course, there was no way to recreate that on the album — even with a figure as creative as Meshell Ndegeocello co-producing with Wilkins. But, fresh off translating her own multimedia stage work No More Water: The Gospel of James Baldwin into album form, she helped bring the rest of the “cooking” to the recordings.

It’s at once earthy and sophisticated, looking back and looking ahead. Like the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane it holds echoes of Africa and India, but also adds voices and sounds of the streets in several of the short sound-collage interludes that dot the work. The latter were suggested by Ndegeocello, who had connected with Wilkins when she recruited him to play on her Sun Ra tribute album for the Red Hot organization. Coltrane, of course, was from Philadelphia. Barron, too. Sun Ra as well—if by way of Saturn. Sitting in his hometown, even if his parents don’t know about it, Wilkins embraces the crucial role his roots and his family play in this project.

“I’m referencing things that have to do with generations of Philadelphians on my mother’s side or generations of musical practices on my father’s side in Virginia. It’s an experiential thing. We learn a lot from lived experiences. But maybe that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The full iceberg is stuff to be investigated in your DNA. We can’t even be responsible for a lot of those kinds of things we may gravitate towards. Even in improvising, what concepts I might be referencing might be coming from things that didn’t even come in this life. And by this life I don’t mean like multiple lives, but I do mean lives of maybe people in my family or my bloodline that I know or don’t know.”

It’s right there in the title.

“Yeah,” he says. “Exactly.”

He nods to his hometown’s jazz saint as a key figure in his blues bloodline.

“If you think about John Coltrane he was trying to get to maybe one or two things for his entire lifetime,” he says. “And I think that’s something that is really emblematic of how I look at my creative output, putting together records or working through ideas, like the concept of a vessel is something that like from The 7th Hand, maybe a vessel for your family, maybe a vessel for ancestors. And I’m always thinking about spiritual practice, thinking about Black aesthetics, all the liberation movements and maybe my work can do something concrete. Like with Blues Blood the goal is that, so there’s a cook on stage who cooks throughout the set. The goal is maybe make this into a cultural outreach project where we’re able to really feed people after the show, people maybe in need, college students, anybody who wants a hot meal can come get some food. Just thinking about the ways that music can have active effects, music that’s about something. It actually does something. I’m interested in stuff that does things.”

What this album does is firmly establish Wilkins as a figure at the forefront of a wave of artists personalizing, expanding, and redefining the concepts of jazz itself, arguably to an extent and with a vision not seen since Miles Davis went electric. We’ve seen Kamasi Washington, Robert Glasper, Salvant and others staking their ground. With Blues Blood, this is Wilkins’ moment.

“I’m feeling a certain level of freedom,” he says. “I no longer feel afraid in a lot of ways. I think recording two albums and having them under my belt has given me a certain comfort in myself, a certain, I don’t know, self-assuredness where I’m more confident in taking some risks.”

Among the risks was including vocals for the first time on one of his albums as well as electric guitar, with Marvin Sewell diving headfirst into distortion on several of the songs. And there’s simply the album structure itself, drawing on that live presentation, and the adding of the interludes.

“During this project I’ve just been much more confident in trusting my intuition and trying to make some stuff that isn’t necessarily about an agenda, like pushing an agenda of jazz or something,” he says. “It’s just about making music that feels honest and feels like some cool stuff, you know?”

The coolest stuff here, perhaps, is in the vocals, with melodies full of engaging twists and emotional resonance. He eagerly shares credit.

“There are a lot of open sections in which Ganavya and Yaw are doing a lot of improvising,” he says. “These spaces I kind of built via really getting inside of all the singers’ practices. I did a super-deep dive on Yaw, a super-deep dive on Ganavya, a super-deep dive on June McDoom. I wanted to give them space to be able to do their thing on it. I didn’t want them to feel like they were adjusting. I wanted it to feel like home for them.”

And, as he sits in his hometown, he wants that feeling to reach those who hear it, now and in the future. Looking back and looking ahead. Way ahead.

“I’m thinking of the work as stuff that maybe happens in the now, but becomes some sort of quantum time capsule for people 20 years down the road, 200 years down the road. Maybe, maybe my children’s children’s children gravitate toward music and reference traditions we played on the X concert or the Y concert, unbeknownst to them. I haven’t really been able to trace my bloodline back too far. Obviously a big part of that is because of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. But thinking of little traces of ancestry that I do learn from my parents or my aunts and uncles and hearing that, oh yeah, there was a musician here, even without knowing that I wonder what’s being referenced in my music. I wonder what’s being referenced in Ganavya’s translations of 2,000-year-old Tamil poems, or Yaw’s poems from Ghana, and the way Kweku plays the trap drum set, maybe not a uniquely African instrument, but in a way that’s transmuting West African themes. I wanted to make something that felt like a time capsule. Something people could go back to in the future and look at this line and say, ‘Okay, this is blues blood.’ And maybe that can be in some way traced to discover yourself, just like we discover ourselves through the music that we listen to.”

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.