T

HE GREATEST BRAZILIAN JIU-JITSU fighter in the world is looking to fight me.

“Put your hands up,” Rickson Gracie tells me as he advances. “Like you’re talking like an Italian.”

I raise my hands as he lunges toward my head.

“Don’t let me touch your face.”

Gracie — the 63-year-old legend with shorn hair and tanned skin — is wearing gray shorts and a black T-shirt. He’s muscular and compact. I’m taller, but that’s about it. He can choke me unconscious with little to no effort. His hands shoot out, but I guide them away using leverage and his own momentum, mimicking the techniques he showed me seconds before. There is an intensity to the way he coaches me through the movements: how to shift my weight to address the threat — sometimes on the front foot, sometimes on the back foot — but always in balance. His brown eyes are fierce, intimidating — he’s focused on my every move and reaction. When you do something right, you get a satisfied, elongated “Yesssss.” Make a mistake and it’s a sharp “No.”

When he does put his hands on you, his grip is firm. His language is action. The product of a lifetime of practice. He is at ease as he teaches. An hour earlier, Gracie had appeared uncomfortable as he tried to sum up his legacy and his last fight, against Parkinson’s disease, with words.

Gracie, whose surname is synonymous with Brazilian jiu-jitsu, stands as a legendary figure in the combat-sports world. He claims more than 400 unofficial victories around the globe as he’s dominated the sport since his first fight, in 1980.

But his legacy is tied to his family’s role in weaving Brazilian jiu-jitsu into the world’s zeitgeist. Everything from the $10 billion Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) to the academies in the strip malls across America exist because of the Gracies. No other legendary fighter or athlete is as responsible for the creation of a sport as Rickson and the Gracie family, making them not only part of the Mount Rushmore of Brazilian jiu-jitsu, but also the architects and sculptors.

In a family of champions, Rickson Gracie is revered for his unmatched technical prowess, dedication, and stoic philosophy — his greatness casts a long shadow.

At training seminars Gracie hosted, he would line up black belts and fight each one in turn, and beat them all. Even Chuck Norris, who helped launch martial arts in America, couldn’t hang with Gracie. “I got on the ground with Rickson Gracie, and it was like I’d never had a lesson in my life,” Norris, a martial-arts legend and actor, told fighting-combat website Bloody Elbow. “He played with me.”

Brazilian film director José Padilha wrote the preface to the Brazilian translation of Gracie’s biography. He compared him to Pelé, the transcendent soccer icon and most-famous Brazilian athlete. Pelé was the best in the world at what he did.

Gracie is the same.

“When you crown somebody the best in the world, you make a mistake of ignoring other sports,” Padilha says. “Gracie is as good as Pelé. There’s no difference. Like, when Pelé was playing, he was dominant. The best player on the field. Everybody on the other team wanted to stop him. [Gracie] had a similar relationship to jiu-jitsu.”

But now, Gracie is facing an opponent he knows he can’t beat.

It was nearly three years ago when he first noticed the subtle tremors in his hand. A year later, his doctor’s diagnosis confirmed the worst — Parkinson’s disease. Muhammad Ali died from septic shock related to his Parkinson’s diagnosis.

Gracie announced the diagnosis earlier this year in a podcast interview with Kyra Gracie. Parkinson’s is a nervous-system disorder that causes vital nerve cells in the brain to die, cutting production of dopamine, a chemical that helps the brain control motor skills, causing tremors in the hands and diminishing the ability to move. Left untreated, people can be bedridden in 10 years. Life expectancy is reduced.

The potential connection between head trauma — which is prevalent in combat sports like boxing and mixed martial arts (MMA) — and Parkinson’s has been debated since 1817, when James Parkinson provided the original description of the disease. Studies have shown a head injury can increase the risk for developing Parkinson’s.

A 2006 study investigating the connection between head injuries and Parkinson’s disease in twins revealed that individuals with a history of head injury had a significantly higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. A 2018 Boston University School of Medicine study also found that individuals with a documented history of mild traumatic brain injury had a higher risk. While both studies show connections, neurologists have not definitively linked head trauma with the disease. Regardless of the links, Parkinson’s is Gracie’s last opponent

I interviewed Gracie two years ago — around the time he got the diagnosis — to discuss his bestselling biography, Breathe. We’d met through Peter Maguire, his biographer, student, and friend. At the time, I didn’t notice the tremors. To me, he appeared to be slowed by age and a punishing fighting career, but still moved with an athlete’s grace.

“We suspected that he had it for a while,” says Maguire, who co-wrote Breathe and is working on a second volume, about Gracie’s battle against Parkinson’s. “It was sad irony. I don’t know anyone who had better control over their body at the height of their powers than Rickson.”

In July, I meet Gracie at his academy in a Torrance, California, industrial park. It’s a spartan space with a training area and small office. Gracie is puttering around when I arrive. We settle into two chairs near the mats. It’s impossible not to notice the Parkinson’s as he sits across from me. His knee bounces as if he is entertaining a baby. His hand shakes. A constant tremor rolls through his body.

But Gracie tells me he is used to the symptoms. For him, Parkinson’s is akin to an unwelcome person occupying the passenger seat in a car, refusing to stay silent. Determined to regain control over his body, he shares his metaphorical remedy: “I put Parkinson’s in the trunk.”

“I’m not scared of death,” Gracie says. “Everybody is going to die. But quitting is not an acceptable option.”

BORN IN RIO DE JANEIRO in 1959, Gracie earned a black belt by the time he was 18. Helio Gracie, Rickson’s father, challenged all comers to a fight at his academies in Rio de Janeiro. The family’s reputation grew as they won match after match, eventually launching the martial art into a global phenomenon embraced by everyone from MMA fighters to Hollywood actors to celebrity chefs, like Anthony Bourdain.

“I represent an art,” Gracie tells me as a portrait of his father watches from the wall behind him. “I represent a lifestyle. I represent a family. So, this representation is overwhelming. It’s bigger than my life. I was willing to die.”

As a member of the first family of Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Gracie is considered the best of them all. I asked what made him so much better than his kin. Gracie tells me he was more athletic and he had flawless technique. But, according to Gracie, it was his will to win that made him different.

“I’ve been undefeated all my life, basically,” he says without a hint of irony. “I could put my hands on different styles, and I’ve been very successful.”

Gracie beats Yuki Nakai in Tokyo in 1995.

Gracie’s first professional fight was Vale Tudo — a no-rules, bare-knuckle MMA bout — with King Zulu in 1980. He went on to win two Vale Tudo tournaments and three MMA matches in Japan between 1994 and 2000, defeating Japanese fighter Masakatsu Funaki in a million-dollar fight in front of more than 40,000 in the Tokyo Dome and 30 million more on pay-per-view in 2000.

The game-changer was when he left Brazil. Growing up, he wanted to come to the United States because he saw it as the place to grow his dream, to create the lifestyle he wanted.

“I was excited from day one to be here and to raise my kids,” Gracie says.

He came to Los Angeles in 1989 to help his brother Rorion Gracie as an instructor. It was Rorion who popularized Brazilian jiu-jitsu in America. Soon, Rickson opened his own school.

Prior to Brazilian jiu-jitsu, the wider martial-artist community was enamored with Bruce Lee and kung fu. It was a lot of impractical kicks and punches that looked better on film than on the street. The Gracies arrived with a martial art built on fighting on the ground, something no boxer or kung fu fighter practiced — meaning a lot of people got the shit beaten out of them.

The “Pico academy” was on the corner of Sepulveda and Pico boulevards in Los Angeles, tucked next to an old body shop. It was hot in the summer. Cold in the winter.

“It was all bad, like a bad old building,” Gracie tells me. “But it was just new champions being raised in there.”

Gracie started with classes three nights a week, and shared the space with a karate dojo. That evolved into morning and evening classes, and finally he took over the whole space and offered classes every day. “It was probably the best martial-arts school in the United States,” Maguire tells me.

The academy is now a fabric store next to a 99 Cents Only Store. Maguire remembers Gracie’s English was weak when they first met. At the time, Gracie was teaching and surfing, with the latter coming before the former.

“If there were good waves,” Maguire tells me, “he wasn’t coming to class.”

When he did teach, the classes were brutal. Maguire says he attended the lunchtime lesson, which was usually a mix of cops working the night shift, weed dealers, and slackers without day jobs. Maguire calls it “lunchtime at the prison yard.” Training started with a nearly one-hour warmup followed by two hours of punishing techniques and sparring. Maguire used to take two shirts and change after the warmup. “I was an experienced martial artist,” Maguire says. “And those classes would take you to the limit of your ability.”

Gracie was willing to fight anyone, anywhere to prove Brazilian jiu-jitsu was the martial art above all others. And he proved it repeatedly. Stories about these challenge matches spread, and fighters went looking for classes to learn how to fight and win.

“I’m watching these scrawny Brazilian dudes just jack everybody. Like world-class kickboxers much better than me,” Maguire says. “And I’m like, ‘Oh, this is scary.’ So, you figure, ‘I better learn this.’”

Few fights capture the Gracie challenge more than when he faced off against Yoji Anjo in December 1994. The fight came after Gracie dominated Japan’s first Vale Tudo tournament, in 1994. Afterward, mixed-martial-artist Nobuhiko Takada challenged Gracie, who told the Japanese fighter to sign up for the next event. Takata’s protégé, Anjo, followed up his mentor’s challenge by going to Los Angeles.

“They usually never show up,” Maguire tells me.

Gracie was always ready to fight, so he just let the “dogs bark,” according to Maguire. But this time, Anjo showed up at the Pico academy with a group of reporters and promoters and challenged Gracie, accusing him of being a coward.

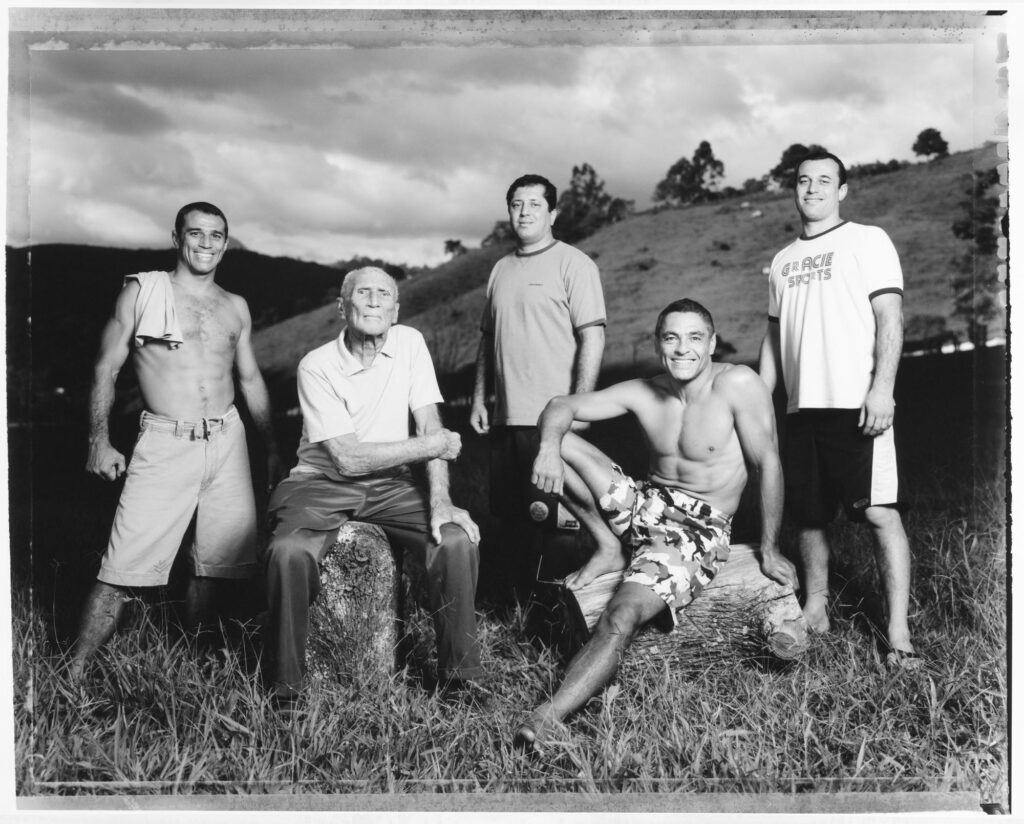

Jujitsu master Helio Gracie (second from left) with his sons (L-R) Royler, Rolker, Rickson, and Robin.

Gracie was asleep at home. His son drove him to the academy as he taped his hands. Only Anjo was allowed into the academy. Gracie’s students kept the promoters and press out. The fight started, according to Maguire, with Anjo throwing a few kicks. Gracie told him he was still warming up. But when Gracie was ready, he took Anjo down to the mat. The Japanese fighter stuck his thumb in Gracie’s mouth and tried to fishhook him, which is popping your thumb through the guy’s cheek. After the fishhook, Gracie decided to send a message. He removed Anjo’s thumb from his cheek and got him in a hold he couldn’t escape.

Blow after blow rained down until Anjo’s nose was flat. After the beating, Gracie choked Anjo unconscious. A couple of days later, Anjo was back, but this time with a samurai helmet and an apology.

Chris Haueter, one of about a dozen American competitors to earn a black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu, was part of the early cohort of Gracie students who, like Maguire, wanted to learn Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

“They had muskets,” Haueter tells me about the fighters they fought from different disciplines. “We have M16s.”

THERE IS A 100-FOOT-TALL sand dune on the Pacific Coast Highway about 30 minutes from Malibu, across from Thornhill Broome State Beach. Most weekends you’ll find tourists trekking to the top on a well-worn path of footprints in the soft sand. At the top, the crystal blue of the Pacific stretches out for miles. But in the early mornings of the 1990s, at the height of his powers as the world’s best martial artist, Gracie feared that sand dune.

At dawn — well before the tourists huffed and puffed their way to the top — he’d drive from his house in Pacific Palisades. He’d park his car along the shoulder of the highway, not far from where the beach spills out onto the asphalt, and with the Pacific Ocean at his back, race through the soft sand to the pinnacle and back repeatedly until exhaustion.

He’d do it knowing that in the ring, when he felt the same tightness in his chest or the exhaustion in his legs, he’d defeated the hill and that he could make it one more time to the top. All fighters have something that convinces them they are the toughest, Maguire tells me. Muhammad Ali would run up Sculp Hill Mountain. Mike Tyson boxed 10 to 12 rounds every day. Marvin Hagler ran in combat boots.

For his Parkinson’s fight, Gracie swapped the dune for protocols. After his diagnosis, doctors initiated the usual treatments, primarily pharmaceuticals, which alleviated some of his symptoms but failed to address the larger impact on his lifestyle. But the medicine’s side effects made Gracie feel worse.

“To me, blindly following the risk-averse American medical establishment is to trade my sword and shield for a shovel that I will be digging my own grave with,” Gracie told Maguire during one of his book interviews.

Gracie began augmenting his treatment with changes to his diet and exercise. He no longer eats beef and flour. And he began fasting, which took him down the rabbit hole of water chemistry, as the acidity levels in bottled water impacted his condition. He couples all of it with the same punishing workouts that kept him fighting fit.

“I engage in intense physical activity,” he tells me. “Bicycling, swimming with resistance gloves and footwear, and even using a swimmer’s snorkel to enhance my workouts. These exercises have become my daily companions.”

Gracie’s protocols are a source of motivation and hope, but they are also like the sand dune: a confidence builder in the toughest match of his life. We are all going to die, but when doctors give you a Parkinson’s diagnosis, they’re giving you a preview of the last chapter of your story. Barring an accident, he knows what will end his life. How does a man who put himself in harm’s way in fight after fight deal with a tremor in his hand that is probably going to get him?

“If I were 17 years old and got diagnosed with Parkinson’s, maybe that would be the toughest because I haven’t experienced much of life, and I didn’t know what I was about,” Gracie tells me. “But today, I’ve done so much in my life. I know who I am. Now I have to make Parkinson’s adapt to me. It’s not happy news, but it’s news I can deal with in the most comfortable way possible.”

Over the past decade, injuries, and now Parkinson’s, have led Gracie to new ideas about jiu-jitsu — a more spiritual side, by tapping into a person’s full potential through confidence. The idea to win a fight without fighting. He calls it invisible jiu-jitsu.

This new spiritual vision of jiu-jitsu comes in part because of his oldest son’s death.

Born in 1981, Brazilian jiu-jitsu came easily to Rockson, who was one of the hottest prospects to come out of the Gracie family. When he turned 19, he left Los Angeles for New York with his sights set on a modeling career. Rockson drifted from his family, and a year later, in January 2001, his body was identified from an arm tattoo. It said: “The Best Father of the World: Rickson Gracie.”

New York police had recovered Rockson’s body in December at the Providence Hotel in Manhattan. The cause of death was a drug overdose. Rockson was buried in a pauper’s grave. He was exhumed, and his ashes were spread at a beach in Malibu.

The tragedy led Gracie to reevaluate his life. He canceled his next fight and never fought professionally again. He battled depression and got divorced. After meeting his second wife, Cassia, he returned to Los Angeles. Despite a life of victories, the loss of his son was almost insurmountable.

“When I came back, I was not exactly in the perfect age or practice to become on top of my game again,” Gracie says. “But eventually I got over and started dealing with the life and family, and I could take my life in a good way, positive way.”

To cope with the grief, he had to find a new vision for Brazilian jiu-jitsu, one of the heart as much as technique. He wants invisible jiu-jitsu to be his legacy.

“You can really heal people,” Gracie tells me. “People get affected by jiu-jitsu in a positive way, which makes me feel like I’m in a desert but I have the water. And that becomes not something to build my ego, but to feel my value and how important this water is for people who [are] thirsty.”

Invisible jiu-jitsu lacks the focus on combat and proving it is the martial art above all else. It stresses inner growth, and self-evaluation, and building the confidence to find your best self. Gracie struggles to explain what it is exactly. It seems to be mostly stock motivational platitudes about tapping into your potential and building confidence that feel more at home in Tony Robbins’ mouth rather than in Gracie’s.

In some ways, it comes from Gracie’s inability to be the athlete he once was. Over the past decade and a half, he’s been plagued by injuries in his hip and back. The pop-up on his surfboard was slower. The joy of fighting was gone. That forced him to dig deeper into what jiu-jitsu meant to his life, not just what it meant on the mat. His focus went to the mental aspects. The confidence. Strategy. Perseverance. He calls them the invisible tools of the martial art.

“I start to become more comfortable with the aspect of winning without a fight,” Gracie tells me. “I’m still highly motivated to express my art of jiu-jitsu, in a different way — not as a competitive as I was before, but in a way to give you more self-knowledge.”

Padilha, who has trained with Gracie, argues that’s because Gracie understands things physically.

“If you explain something to me, some complex movement, like a yoga position, I would create a mental image in my mind and try to make my body fit that,” Padilha says. “Gracie doesn’t do that. This is not how he learns. He does it experientially. I think he absorbs knowledge through his body more than through his intellect.”

Which makes his diagnosis all the crueler.

Parkinson’s is a physical disease, and Gracie has lived a life where his body was his business. He has a hard time in interviews explaining things, but he can show you. As soon as he touches you, he is calibrating. When he shakes your hand, he looks you dead in the eye. As his right hand firmly clutches your right hand, his left hand runs from your tricep to your lats, searching. Like he is reading your mind.

Gracie articulates his pedagogy with movement and action. In many ways, words do him disservice. Until he put his hands on me, I didn’t understand his genius. Afterward, his mastery is clear. Gracie told Maguire that I couldn’t write about him and Brazilian jiu-jitsu without feeling it. He was right.

But his last fight won’t be won on the mat. Yet Gracie takes on the challenge in the only way he knows how — grappling with it head on. “I see myself as a preacher,” he tells me. “I’m not here to say I’m defeated by Parkinson’s. I’m here to say I’m fighting Parkinson’s to win until the last day.”

Because the arena is where Gracie feels most alive. He finds relief in fighting, win or lose.