Róisín Murphy has always made a point of standing out. For nearly three decades the Irish diva has pitched herself as your friendly neighborhood pop star; a couture-clad weirdo at odds with her surroundings but at ease in the world. In the tradition of David Bowie or Grace Jones, she’s capable of bridging haute art sensibility with down-home naughtiness; a fashion week fixture, “KLF MILF,” and “JG Ballard sexpot,” who’s still an absolute scream down at the pub. Her career looks like a traditional glam blueprint, which is to say a whirlwind of references, identities, and genres, all phrased as a sexy, mischievous kind of dare: Why don’t you dress up too? Even though she presents in an outlandish way, escapism has no place in Murphy’s music. What you get instead is an artist wrestling with the problematics of being a person in the world, until through a feat of style, she’s charted her own way out and through.

After a string of releases in the 2010s that spanned Italo-pop to prog-disco, the pandemic imposed an especially dramatic set of limits that Murphy’s music seemed uniquely poised to meet. Where other artists in the incongruous disco boom of 2020 went for broke on dancefloors that would be shuttered for months, Murphy was able to tap into the genre’s cathartic undertow, foregrounding yearning and resilience even as she was high-kicking in a Balenciaga gown in her living room. A song like “Murphy’s Law,” which rages against fate while insisting on “making my own happy ending” came as a revelation, especially since everything that could go wrong, had indeed gone wrong. “Everyone had this response, like, ‘You’ve saved me,’” she expressed in an interview with Pitchfork in June, “I’ve never lived through a time where music suddenly became the most important thing in people’s lives. They poured themselves into it.”

It’s almost impossible to imagine Hit Parade being received in remotely similar terms. The cache of goodwill for the singer seemed to evaporate almost instantly upon the news that Murphy had written that young trans people are “little mixed up kids” and that “puberty blockers are fucked” in a private Facebook comment. A screenshot of her comment rippled through social media and many fans, especially those in her sizable LGBTQ fanbase, were met with bewilderment, anger, and disappointment. A few days later, she issued a statement that included an apology for “comments that have been directly hurtful” to her audience, stating they were made “out of love for all of us” and that she would no longer share her feelings about the issue publicly. You could feel all the excitement surrounding Hit Parade being sucked out of the room.

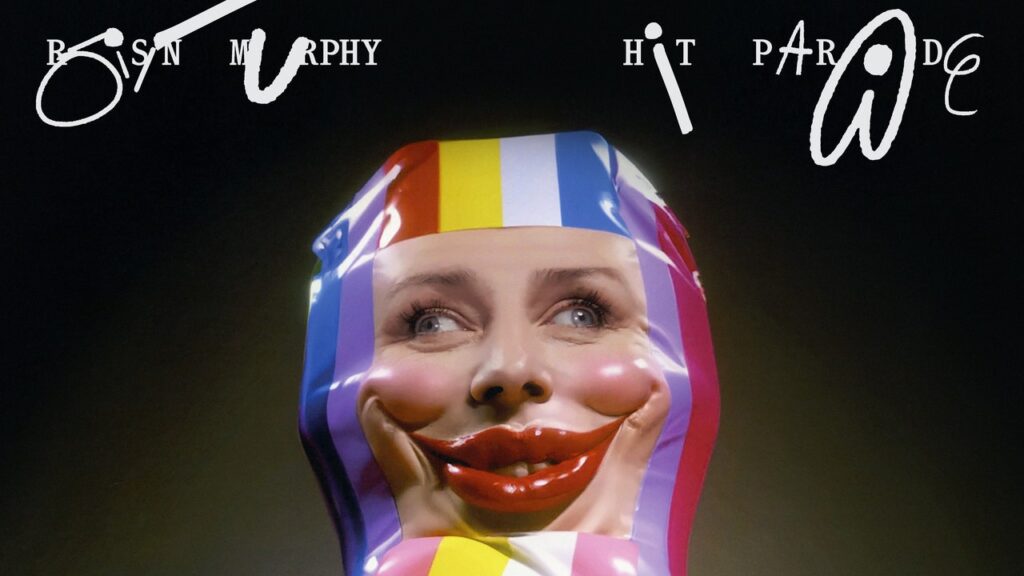

With her masks and costumes and make-up, Murphy’s act is seemingly all about the fluidity of identity and suspended reality on the cusp of a breakthrough. Despite her saying that her “true calling is music, and music will never exclude any of us,” her comments feel like a contradiction to the spirit of her best work. The truth is that Hit Parade is the best record of Murphy’s career; it also feels like the definition of a qualified triumph. It is both musically vast and hemmed in by its circumstances, a showcase of everything impressive about the musician sapped of the excitement that has historically made her work feel so vital. Like the album’s cover art by Beth Frey, Hit Parade is colorful, fun, and unwieldy, but also vaguely disfigured in spite of itself.

Where 2020’s Róisín Machine proved her mettle as a disco queen, very little on Hit Parade resembles any kind of a straightforward genre exercise. House bangers are pitched-shifted and sped up into digitized slurries, while detours into funk and disco are derailed by peels of dissonant electronics. A large part of the record’s chaotic alchemy boils down to the dialogue that played out between Murphy and executive producer, DJ Koze. Over the course of almost six years, the duo cycled through version after version, tearing down and reinventing fully completed songs before Murphy would put her foot down when they’d landed on something really good. “Two Ways,” which was initially conceived of as a country song, pits the singer’s warbling vocals against a heaving slice of corroded mutant trap, while the effervescent “The Universe” manages to stay the course while swerving from bluesy guitar-pop to demented spoken word to an interpolation of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and back again.

From Maurice Fulton to Matthew Herbert, Murphy has been blessed to collaborate with all-star dance producers throughout her career, but none have matched her for sheer off-the-walls weirdness as perfectly as DJ Koze. From their first collaboration— the dazzling astral house of “Illumination” off of Koze’s 2018 album Knock Knock— the duo have smuggled moments of absurdity into the mix that only heighten the music. The put-on American accent that Murphy affects on “The Universe” and “Crazy Ants Reprise” strikes as both a call-back to her old days in Moloko, an outgrowth of the characters she plays on TikTok, and a hybrid of Koze’s own love for babbling non-sequiturs. On “The House,” an incredibly sticky funk beat is fraught with anxiety, as Koze stutters and stops the beat for Murphy to interject with a withering “Fuck’s sake!” The tug of war between the song’s seduction and agitation is brought into creepy-camp relief when Murphy belts “this house is our swannnnn song” through a vocoder, suggesting she’s got a piece of soul-devouring horror movie real estate on her hands.

When they’re not seeding their tracks with brazen silliness, Koze and Murphy have an unrivaled sense of space and sensuality. “Can’t Replicate” is the album’s most glorious high point, a hypnotic deep house banger that makes an unbelievably sexy moment of mutual recognition last until the end of time. It’s also a showcase for how powerful Murphy can sound in moments of vulnerability, giving a performance built almost entirely from exhales that gradually transforms bruised hesitancy into bracing exhilaration. The absolutely devastating “You Knew” is just as moving. For seven minutes Koze sends Murphy’s voice through cycles of processing, repeating and stalling out on the line: “You’ve always known I had feelings for you that burned.’” The effect is of a brain broken by unrequited love gradually re-gaining sentience, and as the sheer enormity of Murphy’s wasted time and effort comes into view, a constantly disintegrating dub echoes her yearning and progressive disillusionment into darkness.

Throughout the record, Murphy wrestles with themes of loss and fate. “CooCool” is an ode to uncomplicated love, tinged from the beginning with the specter of heartache as she whispers “I’ve lost it” before Koze’s beat lifts her rapturously into the sky. The extended metaphors of “Free Will” and “Eureka’” most literally embody these ideas, as Murphy respectively weighs romance so euphoric it feels predestined and dejection so visceral it shows up as a black dot on a doctor’s scan. “Fader” is the album’s most triumphant moment and a clear sequel and call-back to the cosmic, push-and-pull struggle of “Murphy’s Law.” Flipping a sample of Sharon Jones’ “Window Shopping” from a bluesy lament into a fist-pumping high, Murphy sings of holding onto love for as long as she can, death be damned. In doing so she isolates that track’s chorus and blares it like a personal motto: “Keep on!”

Despite the record’s jagged edges, Hit Parade bears a funny symmetry to her solo debut, 2005’s Ruby Blue. A thorny collage of micro-samples, unconventional vocals, and unapologetic artsiness, that album was well-received by critics, but regarded as an inauspicious start for a wannabe pop star; too unnecessarily difficult to ever find a proper mainstream audience. After years spent striving for a breakthrough and many more course-correcting back toward a career as a successful solo auteur, Hit Parade is the kind of highly original pop assemblage that the Irish singer has seemingly always wanted to make, a record of peerless highs whose best and worst quality is how alienating it just so happens to be.