In the summer of 2020, the 79-year-old Linda Martell sat in her daughter’s home in Irmo, South Carolina, recounting a phase of life that had faded nearly five decades prior. She sounded at peace but, at times, still peeved over what could have been. “Don’t get me wrong, there were some beautiful people,” she told David Browne of Rolling Stone, “And some not that beautiful.” The occasion for this meeting was the 50th anniversary of Martell’s 1970 debut solo album, the groundbreaking Color Me Country, which, at the time of its release, was hailed as the harbinger of a new generation of Black women artists who would find commercial success in a genre that had long shut them out. But Martell’s legacy has been greatly overlooked, referenced only periodically in the longstanding criticism of the country music industry’s determination to remain as white and male as possible, regardless of how the nation’s demographics shift.

Martell’s journey began about 30 miles west of where she sat for the Rolling Stone interview, in the small town of Leesville, South Carolina. She was born Thelma Bynem, one of five children, and like many in the African American musical tradition, she nurtured her skills in the church choir. In her teens, she formed an R&B trio with her sister and cousin called the Anglos which, most notably, released a 1962 single with the New York label Fire Records that included songs “A Little Tear (Was Falling From My Eyes)” and “The Things I Do For You.” On the latter, a 21-year-old Martell sings sultrily about the lengths she’s willing to go for the man she loves. It’s the kind of song that could have been a substantial hit if luck had somehow been on their side.

The Anglos played a few shows but never got much traction and soon disbanded. Martell began gigging around the Carolinas as a solo R&B act, and, while performing covers of country songs at an Air Force base, she happened to meet a Nashville furniture store owner named William Rayner. Rayner had record industry aspirations, and when he saw a Black woman playing country tunes, a lightbulb went off. In 1969, he offered to pay for her to cut a demo. Soon after, he introduced Martell to Nashville industry player Shelby Singleton Jr., who had her record a cover of Washington, D.C. soul group the Winstons’ “Color Him Father” and immediately signed her to a one-year contract—with a label literally called Plantation Records.

“Color Him Father” is a song of appreciation for a step-parent who filled the shoes of a father who died in combat, and the Winstons’ version had a rhythmic bounce that allowed the vocals to come across as conversational and charismatic. In 1969, their rendition hit No. 7 on the Hot 100. But in Martell’s sweet reconfiguring, designed to fit elongated banjo riffs and dreamy harmonica play, the intensity of deep familial love cuts through with more emotional precision. Singleton released the single days after signing her and, in the same year as the Winstons, Martell’s version reached No. 22 on the Hot Country Songs chart. From there, she aggressively toured the South to gain recognition, enduring slurs hurled by racist audiences. Her most legendary introduction to the scene was a performance at the famed Grand Ole Opry in the same year she was signed, making her the first Black woman to stand in the circle.

Months later, in a short profile titled “Country Music Gets Soul,” Ebony magazine gushed over Martell’s quick rise to notoriety and how refreshing it was to hear a Black artist incorporate her gospel and R&B roots into country, after opportunistic white acts had spent years stealing “all the little tricks of soul.” The future appeared prosperous. Martell received an offer to host a country variety show and was projected to earn $50,000 (just under $400,000 today) by the end of 1970. But having her value reduced to what kind of money she could make her handlers—projections that regarded her Blackness as a marketing tool instead of a lived experience within an anti-Black society coming out of the Jim Crow era—had severe ramifications.

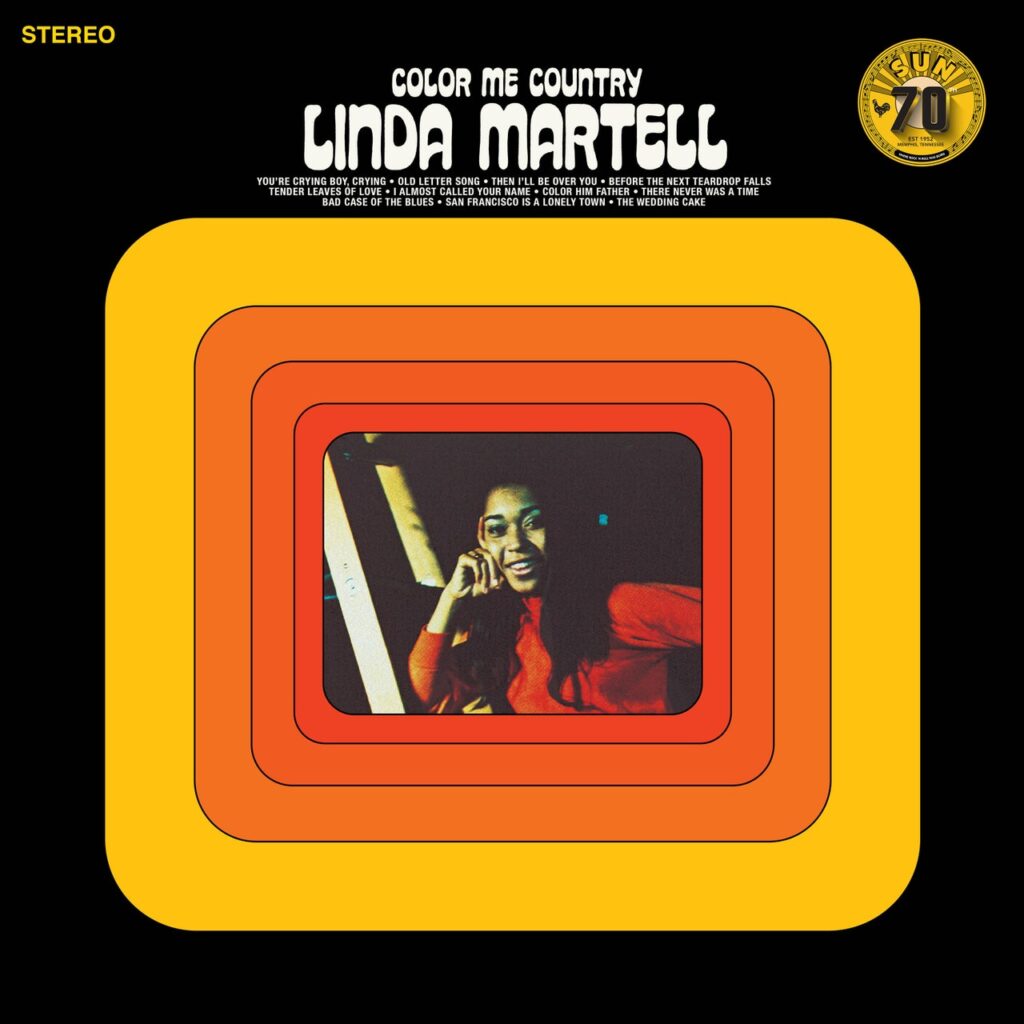

Color Me Country—recorded in one 12-hour marathon session—was released in August 1970. And like Martell’s career up to that point, it performed well, peaking at No. 40 on the Top Country Albums chart. Revisiting the album now, it’s challenging to get a sense for just how much of the South Carolina singer’s true self was ever allowed to be on the project. She recorded a version of “San Francisco Is a Lonely Town” a tale about a couple who takes a Greyhound out to the Bay Area in search of a new life, but soon after arrival, the guy hits the streets, gets wrapped up in the city’s nightlife, and gradually drifts away from his partner altogether. Martell’s inflections when singing, “There were good times for a little while/But now his new friends say I cramp his style/I guess I’m in the way now. He don’t need me hanging ’round,” feature those resonant “tricks of soul” that Ebony alluded to in their profile.

One of the album’s singles, a honky-tonk number called “Bad Case of the Blues,” is directed at another no-good man whom, against her better judgment, Martell’s narrator just can’t let go. Watch the imperial Martell perform the song on Hee Haw: When she yodels, a big smirk streaks across the side of her face. On “Then I’ll Be Over You,” she sings about desperately wanting to recover from heartbreak, yet the production is bare enough that you can get lost in her melodies. Most of the songs on Color Me Country fall somewhere in this thematic range. Martell’s singing is sweet, mellifluous, but the umph in her voice on songs with the Anglos never really shows up here. Maybe it was the anxiety of auditioning for music-industry bosses, rather than collaborating with family; maybe it was the pressure to deliver the kind of mainstream success that now seemed within reach. Still, the conventions of rhythm and blues remained imprinted in her musical DNA.

“When you choose a song and you can feel it, that’s what made me feel great about what I was singing,” Martell told Rolling Stone. “I did a lot of country songs, and I loved every one of them. Because they just tell a story.” Over half of the album’s songs were written by Margaret Lewis and Myra Smith, a duo of white women who are some of country music’s most celebrated songwriters. The songs they didn’t work on were penned by Ben Peters, with contributions from a few others. Relying on professional songwriters was industry standard at the time, but, even today, the merit of a country performer doesn’t necessarily rest on the strength of their pen; rather, it’s their posture and delivery, their ability to make an everyman scenario feel intimate and personal to the listener. And Martell handles business on Color Me Country.

“The Wedding Cake,” which Lewis and Smith initially wrote for country singer Connie Francis a year prior, is transformed from a wistful number to something more vigorous under Martell—a direct result of her gospel-to-soul trajectory. When she sings, “It’s facing shadows of the future, praying they will fall away,” it feels like she’s drawing from the ebb and flow of her personal life. “Old Letter Song” takes an amusingly meta approach, making light of cheesy songs about nostalgia before eventually succumbing to their kernel of truth. And on “I Almost Called Your Name,” a song that’d been recorded by a handful of artists before it reached Martell, she hollers about the awkwardness of finding new love while still hung up on the last dude. Listening to her rendition feels like witnessing a riveting scandal in an audio soap opera.

During that 12-hour recording session, Singleton threw songs to Martell and a team of musicians to perform and, in return, she produced a boundary-breaking piece of art that wouldn’t be duplicated for years to come. But despite her meteoric rise and well-received album, by Martell’s estimation, her momentum at Plantation Records came to a halt when white female singer Jeannie C. Riley of “Harper Valley P.T.A.” fame became the label’s primary focus. When Martell tried to find work elsewhere in Nashville, Singleton thwarted her by threatening to sue prospective new record companies. Her career was left incomplete—a series of dispiriting what ifs? In the decades that followed, Martell bounced around the U.S. doing the music-industry equivalent of odd jobs—singing on a cruise ship off the coast of California, opening a disco and R&B record store in the Bronx, fronting an R&B cover band in Florida—before returning to her South Carolina hometown as a teacher and school bus driver. Even after failed attempts to rehabilitate her career as a recording artist, Martell’s life still orbited around a profound love for music.

In the decades since Martell’s country career fizzled, Black women country singers like Ruby Falls, Rissi Palmer, Brittney Spencer, Mickey Guyton, and others have experienced some semblance of success, though none have charted higher than Martell did over 50 years ago. In 2023, mainstream country music thrives in spite of the demographic and cultural changes taking place in America: The country stars who have enjoyed the most success this year are ones that have, in one way or another, declared opposition to those changes. Country music veteran Jason Aldean’s “Try That in a Small Town,” which has been criticized as a coded call to action encouraging rural white Americans to pick up their guns in the event of perceived unruly behavior, became a No. 1 hit. “Last Night,” a country song decorated with trap-style percussion, sat at the top of the charts for 16 weeks when singer Morgan Wallen re-emerged after saying the n-word on camera in 2021. Perhaps the year’s most surprising country chart-topper is “Rich Men North of Richmond,” from out-of-nowhere Farmville, Virginia singer Oliver Anthony. The song tugs at the frustration of poor and working-class whites who feel stifled by “new” social norms and envious of migrants and welfare recipients; Anthony’s wails add palpable dramatic effect.

“There is no other massive cultural industry where we would accept that it is OK for it to be this straight, this white, and this masculine,” University of North Carolina professor Tressie McMillan Cottom said on a recent episode of Vulture’s Into It podcast focused on country music’s present-day racial dynamics. When Black audiences embrace non-Black artists in genres like hip-hop and soul, McMillan Cottom says, “We don’t just give them an audience, we give them legitimacy. This is what country music denies Black artists. In country music, even when the music is produced by Black artists… it has to be separated from Black people to be considered legitimately country. That’s the difference.”

Those words ring excruciatingly true over the incomplete career of Linda Martell. Money-hungry men from Nashville never considered the singer in her fullness. She was an avatar fixed for white imagination, never granted the opportunity to tell a story that transgressed beyond songs with safe, established themes about women occupied with love (or the lack of it) from men in their lives. Her story inspires its justified share of rage and heartache, but in that same breath, it’s no less remarkable; a Black woman’s voice storming through an industry she wasn’t supposed to be part of, breaking records by sheer existence and leaving hard evidence of the kind of impactful work that outlasts even the hottest commodities of the moment.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.