The Omnichord was developed in Japan in the 1980s as a musician’s electronic accompaniment, incorporating a drum machine with rhythm and tempo controls, a set number of playable chords, and a “futuristic” touch-sensitive synthesizer ribbon. And while it has famous fans—Brian Eno, Joni Mitchell, and Damon Albarn, to name a few—it has always been a niche instrument: It’s mostly made of plastic, it feels like a toy, and it now sounds as cheap as it looks. In the hands of an exacting and protean virtuoso like Meshell Ndegeocello, deep into a decades-long career, the Omnichord became a tool for self-discovery.

In 2020, with no shows to play or sessions to sit in on, she found herself scoring three television shows—BMF, Queen Sugar, and Our Kind of People—simultaneously. At the end of marathon days spent collaborating remotely from her home in Brooklyn with an untold number of artists and executives, she would retreat to her attic. Alone with her thoughts and a gifted Omnichord, she would write, free of expectation, free to find things she wasn’t necessarily even looking for.

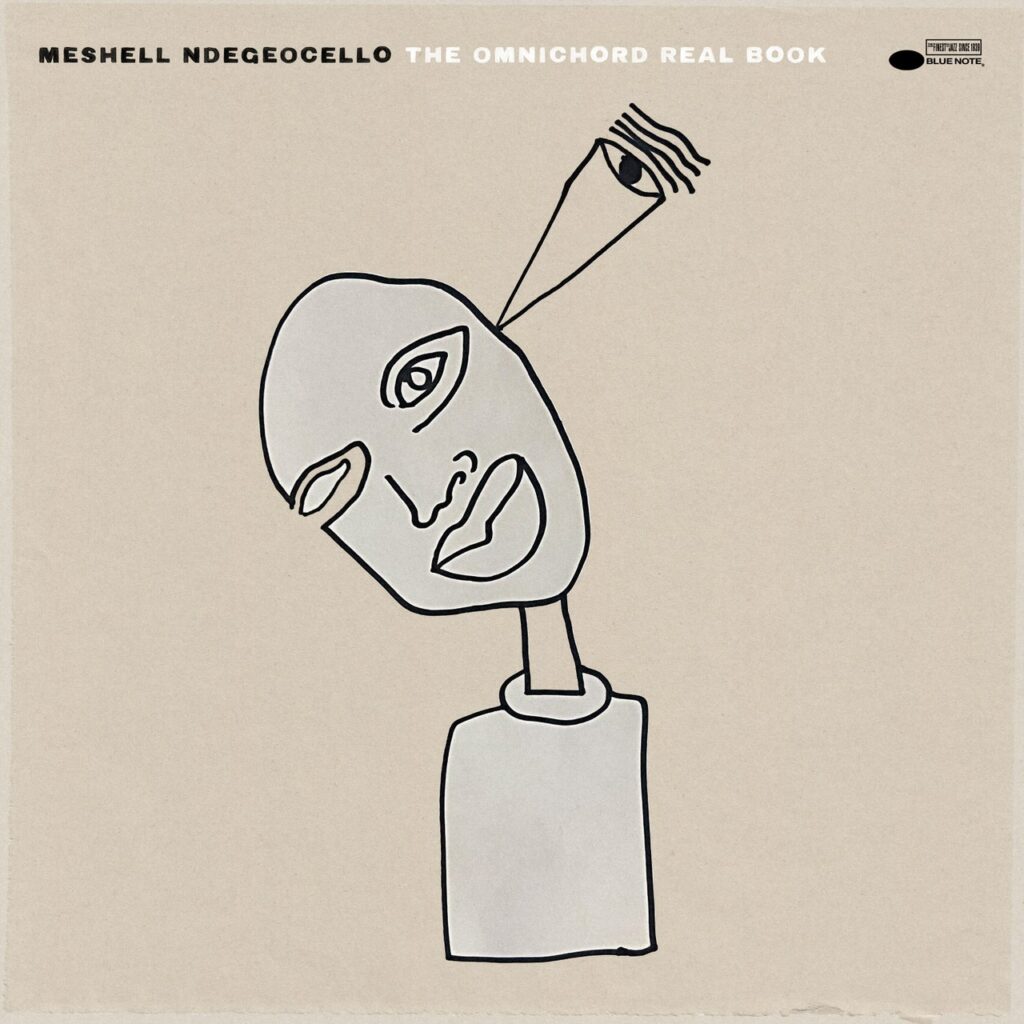

The bones that emerged from the attic would eventually become the songs on her latest LP, The Omnichord Real Book. A sprawling, 18-track album dosed with free jazz percussion, bass-driven funk, a capella beats, and gentle acoustic fingerpicking, the record feels like a natural synthesis of the jazz, rock, dub, and soul sounds she’s explored throughout her career. Ndegeocello has always had a forward-facing view, experimenting with new styles from album to album and serving as a chameleonic session musician for a wide variety of artists (Madonna, the Rolling Stones, Gov’t Mule). The expansive Omnichord Real Book draws on that history of shape-shifting and turns it into something both recognizable and new.

It’s her first release for the storied Blue Note imprint (a label she “dreamed about as a child”) and feels like a genuine reset in a career that has had several to date. Ndegeocello spent much of the last decade saying goodbye to her parents; after her jazz saxophonist father died in 2016, her mother suffered from dementia for years before passing in 2021. “I have no one to blame anymore for my inner hurts,” she told the Guardian. “No one to please. No one to miss.”

The album’s title references The Real Book, a collection of “lead sheets” for jazz standards that’s been published in various editions since the 1970s; sifting through her father’s things after he died, she came across the first copy he ever gave her. The function of a Real Book is to give musicians the bare minimum of information they need to perform a tune—usually just the melody and the chord changes—and it’s up to the player to bring the song to life. And indeed, while the Omnichord’s tinny electronic tones are the first we hear on album opener “Georgia Ave,” very little survives the record’s final mix. Ndegeocello’s early sketches give way to a richly produced coterie of live instrumentation from the session vets in her band and a coterie of collaborators at the forefront of contemporary jazz.

The transformation is by design. Many of her collaborators—Jeff Parker (guitar), Ambrose Akinmusire (trumpet), Joel Ross (vibraphone), and Jason Moran (piano)—are masters of improvisation who add new dimensions to the worlds she’s lived in. Funky neo-soul grooves give way to sparse piano ballads, cosmic chords accompany jazzy horns, and twinkling desert blues guitar nestles into psychedelic soul basslines. She does most of the writing, yet can’t help but include other inspiration, like Samora Pinderhughes’ crushing piano ballad “Gatsby,” whose themes of self-reflection (“I been saying things I don’t believe/I been doing things that just ain’t me”) sound like they were written for her.

Through that lens, the sessions can be seen as a rumination on the illusion of control—of ourselves, of others, of the art that they make and release. It balances humility with ego, relinquishing control to artists with their own distinct voices, while offering a new set of standards into the jazz canon that has historically been anything but inclusive.

Ndegeocello’s solo albums—her early work, in particular—were often sexually and politically charged. She explored and asserted her own sexuality, and aggressively confronted the status quo and her place in it as a queer Black woman artist. The Omnichord Real Book is no less assertive, yet feels energized by grace and understanding. She processes shared trauma (“Towers”), communes with the spirits (“Vuma”), and embraces the dream of the unknown (“Georgia Ave.”) Having fought those battles many times over, Ndegeocello feels more concerned with the present, her assertions reflecting a new sense of self and the existential melancholy of a 54-year-old artist who finally feels comfortable enough to imagine the privilege of a dignified death.

This energy coalesces on “Virgo,” a nearly nine-minute Afrofuturist suite that serves as the album’s centerpiece. Her synth bass spends much of the first few minutes in conversation with Julius Rodriguez’s electronic organ as she sings of finding peace in pain; as the groove builds, she expands her gaze outward to the stars and deep space. When Brandee Younger’s harp comes floating into the mix, it’s as if they’ve cleared the earth’s atmosphere, free to roam the great expanse.

It’s often when we’re alone that we consider our connection to others. Alone in the attic with her Omnichord, Ndgeocello drew on the gifts from others that became the basis for her life as a musician: her father’s favorite records, her mother’s melancholy, the go-go music on which she cut her teeth performing in her youth, even the homogenous music industry that forced her to firmly establish her sense of self. And not unlike the lead sheets in the Real Book she first learned from, the songs she wrote remained incomplete until their communion: with her collaborators, with her audience. “The song is the spaceship,” she said in a recent documentary. “We just get in and see where it takes us.”

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.