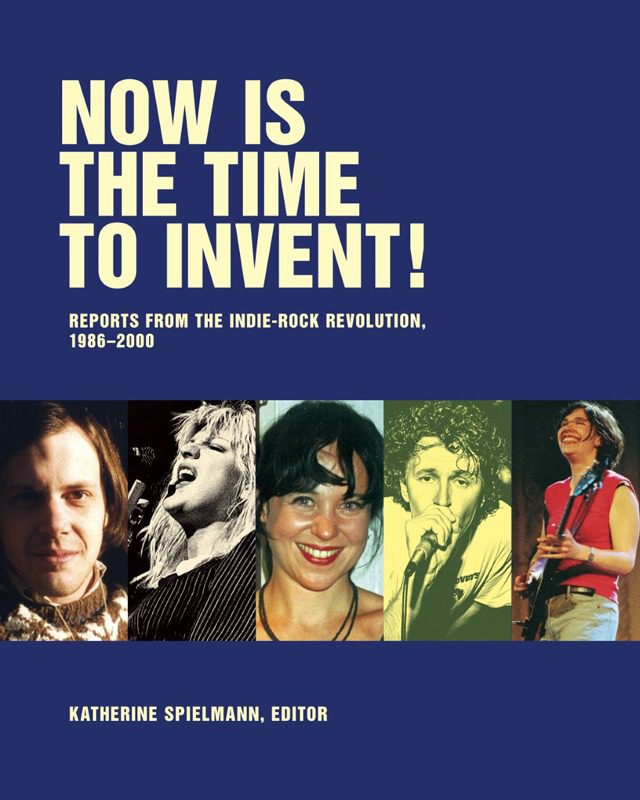

Nineties nostalgia is still peaking, especially these days, when the former decade’s languid news cycle, easygoing economic conditions, and casual creative climate seem achingly distant from the miserable way we live now. And, of course, new bands are bands constantly cropping up that sound like Matador and Kill Rock Stars heroes of the Clinton-era underground. A new book out this month perfectly captures that artistic and cultural heyday. Now Is the Time to Invent!: Reports From the Indie-Rock Revolution, 1986-2000, from Verse/Chorus Press, collects writing from Puncture, a little magazine that covered the indie scene of the late Eighties and Nineties with authority, scope, generosity, and a lovingly critical eye.

Founded in 1982 as a San Francisco punk zine, then relocating to Portland a decade later, Puncture continuously grew, publishing engaging profiles of the indie rock biggies — Pavement, Hole, Beck, Sleater-Kinney, Belle & Sebastian, the Flaming Lips, Cat Power, the Pixies, Nick Cave, Neutral Milk Hotel, the Magnetic Fields, Jeff Buckley, Fugazi, My Bloody Valentine, Guided By Voices, and many more — alongside culture essays, reviews and coverage of film, art, and literature. (Despite its tiny readership, it was one of the few places to publish an excerpt of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest in 1996.)

More than 50 profiles and essays from the magazine’s history are anthologized here, reproduced as they appeared in the magazine, a fitting homage to the media of the time. Puncture existed somewhere in the space between punk zines and a glossy like Spin. Unlike a lot of zines, Puncture didn’t fall back on first-person self-indulgence, nor was it printed on cheap newsprint that left your fingers smudged with ink. (Full disclosure, a piece I wrote on the late singer-songwriter Vic Chesnutt is included in the book.) Like the bands it wrote about, it was informal, yet tastefully made; its pages drew from an inviting palette of pastels; the writing was smart and engaging, enthusiastic but never fawning, concerned with the health of the music scene even when assessing its progress meant calling out its insularity or lack of energy.

There are some fun pieces of history here: a Hole profile from 1991 in which Courtney Love bursts into the interview all aglow that her new boyfriend Kurt Cobain just called her the best fuck in the world on U.K. radio; a freewheeling and funny PJ Harvey piece where she complains about being lumped in with riot grrrl and slags the then-hot Brit band Huggy Bear; an excellent Pavement piece where Stephen Malkmus passingly compares Oasis to porn (“you might want to look, but you wouldn’t want to marry it. Or maybe you do. I don’t know”); a story about K Records cuddle-core kings Beat Happening where they show up to meet the writer with singer-guitarist Calvin Johnson’s eight-year-old nephew in tow (and the kid appears in one of the pictures that accompany the piece); a Sleater-Kinney profile from 1995 when they had only released their first album, and another piece a few years later when they’d evolved to one of the best bands in the world; a profile of the groundbreaking New Zealand band the Clean that opens with a scene of co-founders David and Hamish Kilgour eating chocolate chip cookies in their mom’s kitchen with Robert Scott of the Bats and Martin Phillips of the Chills (in terms of Kiwi-pop history, it’s like being the same room with the founding fathers).

Many Puncture writers were musicians themselves, including Olympia, Washington singer-songwriter Lois Maffeo (who profiles Fugazi), Franklin Bruno of the band Nothing Painted Blue (who writes about Smog and the Go-Betweens, among others); and the late David Berman of the Silver Jews, who interviews Scottish twee-rock icons the Pastels — via fax! — in 1998. Question: “I have a black eye, insomnia and am in the early stages of gum disease. What physical problems do you suffer from?” Answer: “I think I mainly suffer from a lack of sleep.”

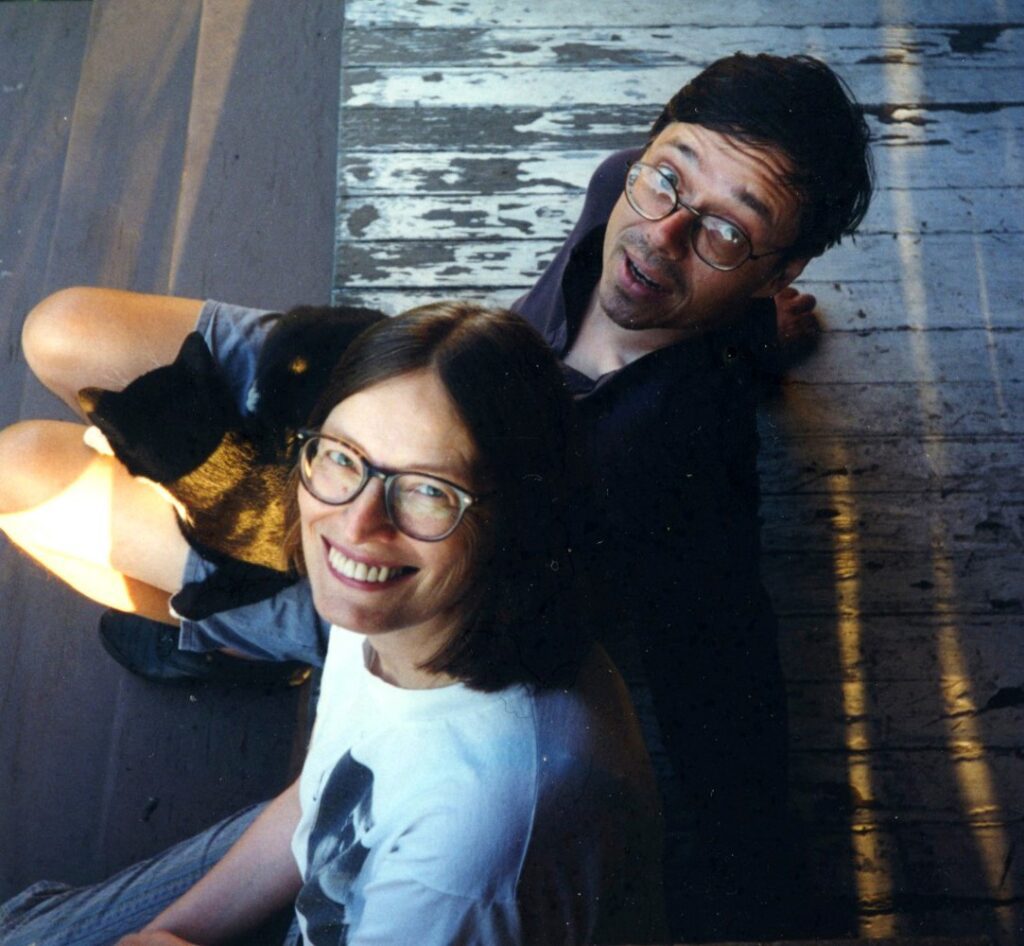

The magazine was steeped in the indie rock community in other ways: photographer Michael Galinsky co-wrote the 1994 cult-classic Half-Cocked, which is set in the Louisville rock scene that produced Puncture profile subject Will Oldham; Gina Harp, who writes about the Breeders, put out the important riot-grrrl EP There’s a Dyke in the Pit on her own Harp Records; before switching to journalism and running Puncture alongside its founding editor Katherine Spielmann, co-editor Steve Connell worked at the seminal London post-punk label Rough Trade and helmed its first attempt at opening an American branch in the mid-Eighties. “We tracked the careers of bands making wonderful, startling music despite the best efforts of the music industry to chew them up,” Connell writes in an introductory essay.

The critical essays included here are a cool reminder of the inter-scene polemics of the time, something Puncture did with a gentler touch than most. In “Women In Rock: An Open Letter,” from 1988, Minneapolis writer Terri Sutton opined, “To me rock and roll is about lust, lust for feeling; the worst I can say about a band is they’re boring. That’s why it’s so crucial that women get up onstage and impart-inspire some emotion.” At the time, the magazine was covering all-woman bands like Throwing Muses and Scrawl, and soon enough, Puncture would be writing about Sleater-Kinney, the Breeders, Hole, Kathleen Hanna and PJ Harvey and other artists who’d arrive to prove Sutton’s words prophetic.

Katherine Spielmann and Steve Connell, 1994.

Courtesy of Carl Campbell

Along with its sensitivity to indie-rock often unbalanced gender dynamics, Puncture also backed the right aesthetic horse by celebrating the homespun, literary, warmly opaque, self-consciously arty, and vulnerable — bands like Camper Van Beethoven, the Mekons, Sebadoh, Palace, and the Mountain Goats. In that Mountain Goats piece from 1994, John Darnielle assures us with total certainty that his band will never record in a real studio, a promise he’s been breaking with wonderfully made records now for decades. Some Nineties dreams were born to die, or rather, evolve.

Puncture stopped publishing in 2000, when indie rock was in one of its intermittent fallow periods, and just as the internet was starting to supplant print media. By writing in an informed, passionate way for fans of the music the writers and editors liked, Puncture was doing for a readership of a few thousand what Pitchfork would soon be doing for a much larger audience online. That’s another similarity between Puncture and many of the bands that appeared in its pages: if the magazine was a little easier to know about, it might’ve gotten a lot more attention. It certainly deserved it.