This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

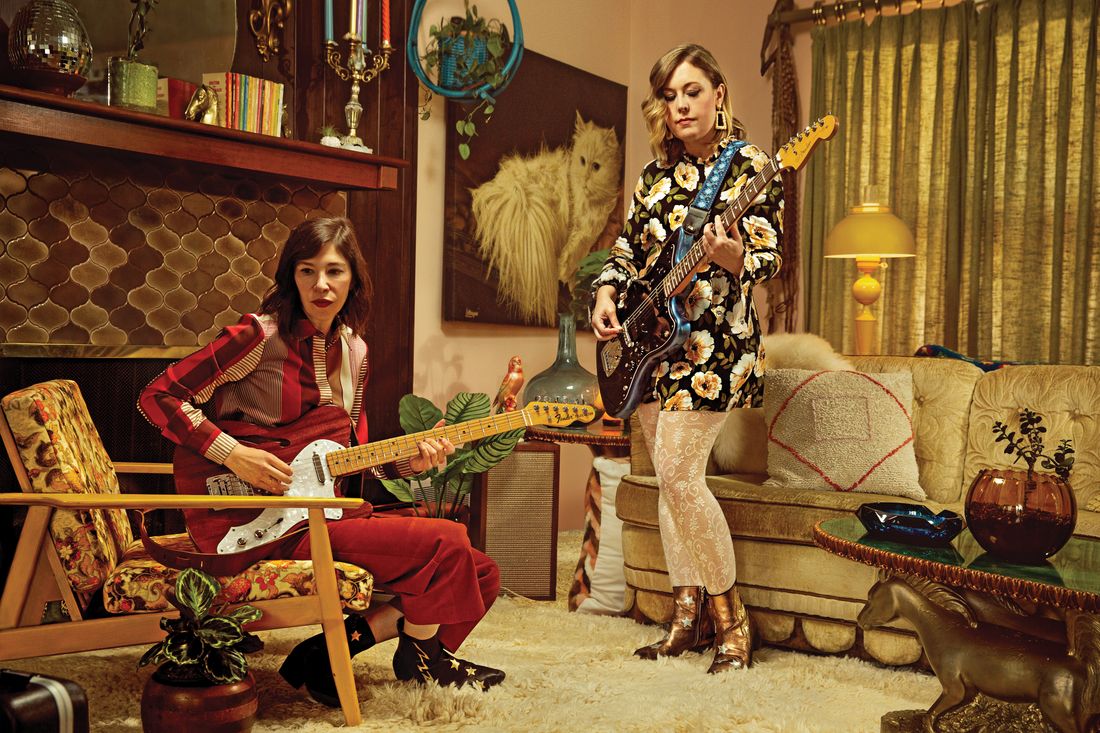

Carrie Brownstein and Corin Tucker recorded Sleater-Kinney’s tenth album, Path of Wellness, in Portland, Oregon, last summer against a backdrop of unrest. For weeks, protesters marched through the city, demanding racial justice while being tear-gassed by the Portland Police Bureau. Brownstein and Tucker split their time among the numbing routines of life in quarantine, protests, and the studio. “It’s not the summer we were promised,” Brownstein croons on “Down the Line,” a gritty rocker situated in the closing stretch of the new record. “It’s the summer that we deserve.”

For Brownstein and Tucker, the album, out June 11, is a recommitment: the band’s first since 1996 recorded without drummer Janet Weiss, who left Sleater-Kinney in 2019 because she felt she no longer had an equal say in its direction. (Brownstein said at the time that this came as a surprise.) The pop-oriented songwriting of the last album with Weiss, The Center Won’t Hold, produced by St. Vincent’s Annie Clark, looked to some fans like a curveball. In contrast, Path of Wellness, the first album Brownstein and Tucker produced themselves, takes cues from Sleater-Kinney’s forebears in punk and classic rock. (Those still looking for more Carrie and St. Vincent lore can check out the forthcoming mockumentary The Nowhere Inn, which stars both.) The title track and opener serves spastic, jagged post-punk riffage and disorienting percussion; later, the chugging “Method” swaggers like ‘70s Alice Cooper, while “Down the Line” tries out the start-stop rhythms and “I know it’s all right” refrains of Led Zeppelin’s “Dancing Days.” The songs are lean and tastefully executed; throughout the album, splashes of notes from bass, clavinet, and Fender Rhodes organ add hues without obscuring the primary colors of Tucker and Brownstein’s guitar playing. (Drum duties were handled by a rotation including their post-Weiss touring drummer Angie Boylan, Brian Koch of Pacific Northwest indie rockers Blitzen Trapper, and Vincent LiRocchi, a veteran of Portland’s music scene.)

The album is, as its title suggests, a song cycle about weathering rough times and learning to live and love again afterward, experiences we’re all processing to one extent or another this year. I spoke to Corin Tucker and Carrie Brownstein over the phone the day after the release of The Path to Wellness’s lead single “Worry With You” this month about making art in Portland while the city battled for its very soul, and the continuing evolution of Sleater-Kinney since reconvening in 2015. “It was like restarting the band again, in a way, during such intense chaos and crisis,” says Tucker. “But it was also something that was joyful.”

Does creating music during rapidly changing times throw a wrench into the process? Do you feel like more is asked of you as a band celebrated for its politics?

Corin Tucker: That’s just part of being human during this year. It’s such a crazy time to have lived through that it just makes sense to me that it would come through in the writing somewhat. I don’t think the record is totally about that, but there are definitely seams of it — thinking about death, and life, and longevity, and mortality.

Carrie Brownstein: I’ve always felt about music that is characterized as political that it still has to be couched in a good song. Otherwise, it doesn’t really have relevance or longevity strictly as a political act. I like the messiness of art and the ability to toy with mythology and fiction and weave those into things that are also more grounded, but I think our goal is always just to write from a place of honesty and earnestness.

The press coverage for the new album so far is zeroing in on the notion that the band is now a duo.

CT: I love it. “Duo.” That’s so funny. I mean, we’re happy with working together and being collaborators. It’s how we started the band a long, long time ago. It was based on our ideas and our guitar playing. We’ve had the great privilege of working with a lot of different people over the years. I think that all came into play when we were putting this record together. We were able to find local people who could come in, amid all the Covid rules, and play on the record.

CB: That “duo” terminology … I didn’t really think about it until I started seeing some of the press, because I just think of us as Sleater-Kinney. Whatever we’re doing as Sleater-Kinney is Sleater-Kinney. I’m aware that people need these linguistic markers to help them understand.

Path of Wellness is also the first record produced solely by the band. Was that a conscious choice, or was it a logistical necessity?

CT: We did think about bringing someone in, and it was really impossible.

CB.: As we were writing and demoing songs, we were adding so many elements. We were working out arrangements and composition and editing, trying different choruses, and changing the top-line melody over and over again. When we had the demos done, they already had keyboard lines and bass lines. I thought, Well, what is a producer going to do at this point? We’ve basically laid out exactly how we want this record to sound. It also felt important to put ourselves on the line again in this way, where we said, “This is who we are. There is nothing mediating this experience. There’s no other entity through which you can filter what this is. This is what we made.”

In 2019, Janet Weiss suggested that she had been shut out of decision-making processes in the band and that was why she left. I’m curious how you feel about that characterization.

CB: I mean, anyone who thinks there aren’t multiple perspectives and sides to this is either being willfully ignorant or perhaps lacks their own real-life experience. To be honest, I’m not interested in continuing to talk about something that really seems to revel in female cattiness and conjecture and confirmation bias.

I do think news of the lineup changing cast The Center Won’t Hold in a certain light. You were working with Annie Clark from St. Vincent, and she’d just put out a record with Jack Antonoff, who had just worked with Taylor Swift. Some people thought the band took a sharp left into pop music and kinda came apart.

CT: Personally, I’m always wanting to try different things and to be creative in different ways. That can be hard sometimes. It can be difficult. It can make you uncomfortable. I think that’s part of being an artist and doing work that keeps you interested over a long period of time. And I feel like we learned so much from the last record, from Annie producing and everything we were trying out. We’d never really written with keyboards. We tried a lot of different things. I’m not saying they were all successful, but it was different. We were able to take those new skills and put them to use on this new album.

CB: I find it really interesting that the same people who reject conservatism [in politics] will insist upon a very orthodox view of this band, that people who rail against binary oppositions on all fronts will settle for reductive, fixed, black-and-white narratives of Sleater-Kinney through refusing to acknowledge nuance or multiple truths. Sometimes it seemed like the reaction to The Center Won’t Hold was more about us refusing to conform to a codified and static version of ourselves. Ultimately, the role of the artist, I have always thought, is to experiment and thrash around and make mistakes and just be out. I’m not saying that’s what we did on the last record. If everyone’s aiming for the same bull’s-eye, you end up with conformity, so we’ve always seen our role as being out of step sometimes with what people want.

In retrospect, it feels wrong for us to have seen The Center Won’t Hold as the end of an era, knowing now how you followed it up.

CB: Annie is a brilliant musician. We learned a lot from her. I think that, like you said, now that that album is part of a continuum, to me, it’s not an anomaly. I also didn’t mind tearing the Band-Aid off and breaking up with some white male critics.

Your new song “Complex Female Characters” pokes fun at the hypocrisy of this time, where we’re hitting all of these diversity-and-inclusion milestones but the overarching power structures in the entertainment industry still favor men. If people are upset when Phoebe Bridgers smashes a guitar on SNL, we’re in the dark ages.

CT: I think rock music has always been behind the times culturally. When I was growing up, women were usually just sex objects in the rock world. It’s still really behind the times — it doesn’t see women as protagonists, as the ones who are controlling things and making things and defining culture.

CB: What was interesting about the Phoebe Bridgers thing is that people celebrate there being so many women who play guitar now. But as soon as Phoebe used the guitar in a way that people associate with maleness, they’re like, “Wait, no, sorry. The guitar still signifies maleness. You’re allowed to borrow this, but don’t forget.” When women step out of the space, the small playground they’ve been allowed into, the pushback is very, very intense. Those moments are a reminder: Let’s not just be asking to get in the door. Let’s build a new structure. I think as much as that was a frustrating moment, it’s always a good reminder that when you are let into the club, burn it down.

CT: Figuratively. Figuratively.

CB: Thank you, Corin.

Historically, one of the great strengths of your band has been minimalism — the tightness of a trio, these interlocking guitar leads chasing each other, not a note going to waste. Is that something you worked out with intention, or is it a learned language?

CT: We recognized from the beginning that we’re very different, musically, Carrie and I. I’m much more of a rhythm-guitar player. Carrie is just a natural lead-guitar player.

CB: There has been a series of happy accidents in the history of Sleater-Kinney. Early on, we fell into these certain roles where, as Corin said, she was occupying what would more traditionally be a bass line, even though she was playing guitar, or rhythm guitar. Corin, as you’ll realize in this conversation, has this really nice steadiness and succinctness, and I’m very loquacious. That’s how we play.

Path of Wellness touches on themes that I think are central to 2021. You have songs about making yourself available for love again and yearning for freedom and coping with political upheaval. Did you do much thinking on a theme?

CT: I think we were just writing with a sense of seeking out our own truth of the moment. Writing has always been a coping mechanism for me to make sense of when I feel really, really overwhelmed. That’s when I’m usually trying to write a song. I think those themes were more about living in that moment than a conscious decision.

CB: When we were writing those songs, we were preparing to go on this tour with Wilco, which was supposed to happen last August — and which is now miraculously happening this August, knock on wood. They felt expansive because we were imagining these outdoor spaces. Then, all of a sudden, it was like all of that air was sucked out. The mode was insular and claustrophobic. Then you’re searching for how to find a sense of freedom and joy and love in the tiniest, smallest of spaces. I do think a lot of the songs are grasping at lifelines. You’re holding this person close, but they also feel far away. Or you’re trying to hold your city close, but it’s in the process of dismantling. Even your own sense of being is recalibrated. I can feel the tension of constriction and expansion in the lyrics.

What was it like to be writing and recording in Portland last summer during that flash point?

CT: It was such a haven being able to go into Halfling Studio and make a record. It felt like the biggest privilege in the world to have that. It was a really difficult time. There were stages where I participated and I was part of the protests, as was Carrie. There was a part of the protests where I was turned off by the violence and the destruction that was happening. There was another stage where the wildfires in Portland were really extreme, where I was watching to see if my house was going to be on the evacuation line. It felt like four different years crammed into one summer, but it felt like shelter going into this recording studio to make music, you know?

CB: I also appreciated, and was amazed by, the way that Portland turned forms of resistance into routine and ritual as well — that it became part of the daily purpose to show up and participate. You don’t have to compartmentalize those things. They can be quotidian. They are constant, evolving. But I also saw the process of making a record as an act of resistance and perseverance. Each of us takes on a different aspect of protest. I think showing up in the streets is one way. Also, creating work in the world that can help uplift people, or help someone get through a day, is another way. It all felt like parts of the same conversation.

Under Democratic presidents, there is just this false sense of security. Biden’s not a panacea. I am not even sure when we got to this place where we loved politicians — this idea that some politician is going to come in and be able to make everything better, whether they’re a Democrat or a Republican. We exist in a time where there are these trends of protest. We have to make it a lifetime of work. That’s exhausting, but it’s also what it means to be human right now.

Outside of music, how did you cope with the pandemic?

CT: It was just really hard to watch my kids go through it, to be honest. I’m old. I lived a pretty good life. I’ve been all over the world. I could rest on my memories. But kids, this is when they’re supposed to be out in the world, and doing things, seeing their friends. Watching that being stripped away was the hardest part for me.

CB: In terms of making things or being creative, I think early on, I felt this sense of failure. Remember there were all these articles about how Shakespeare wrote during a pandemic? We were all supposed to be making amazing art. I’m not comparing myself to Shakespeare. It just felt like, “Well, let’s just sit back and wait. All this great literature and film will come out of this.” I thought, But I can’t get out of bed right now. I don’t know what I’ll be making. I started worrying that I no longer had a sense of what was happening in the world. I came out on the other side with some lightness, but it definitely felt dark for a while.

Carrie, last fall it was announced that you were writing and directing a biopic about the band Heart. Is there anything you can tell us about that?

CB: I’m hoping it’s going forward. I’ve actually been approved to direct. When Ann Wilson, from Heart, mentioned that I was directing last year, it wasn’t official yet. I love Ann for that. She speaks her mind, which is one of the reasons that she’s an amazing human. I will direct it if it happens. Right now, we’re in the casting process, which, as you can imagine, is one of the most challenging things, because you can definitely get it wrong.

How do you find ways to keep surprising each other when you’ve been in a band since the ’90s?

CT: I think Carrie and I are both really open to trying different things. We like working on ideas together, and we’re not afraid of trying something, having it fail, and trying something else.

CB: We have gotten used to that feeling of being exposed in front of the other person. There’s almost nothing more vulnerable and embarrassing than sitting in a room with a very rudimentary sketch of a song — just a fleeting idea of a guitar line or a melody line or a vocal melody — and performing that for someone. I mean, that is not something you would even do with a romantic partner, necessarily. But we have often sat in a room together and just laid bare an idea that could honestly be terrible. To know that the other person is not going to reply with derision or mockery but that they will sit and hear you out …

Corin does surprise me. You hear snippets of something that we might not associate with Sleater-Kinney, like country-and-Western, or R&B, these things that are further back in the DNA of the band, and know that we can shape it into something that fits our vernacular. In the early days, if Corin said, “I’ve been listening to Dolly Parton,” I would’ve been like, “Well, we’re not Dolly Parton.” Now, if she says, “I’ve been listening to Dolly Parton,” I’m like, “Eventually, it’s not going to sound anything like Dolly Parton, but show me your Dolly Parton song.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.